Weeknotes: Doteveryone, maintenance by design, deliveries, writing

Doteveryone existed because of Martha Lane-Fox and she has some great points now, as ever:

We were always clear that we didn’t want to produce reports alone but we must show what “good” looks like – build some products and services that could be used either as examples or as tools for other organisations to use. Some of the work that I have found most powerful has been when we have done this successfully – in the care sector, for gig workers or people who are facing the end of their life. We have always tried to use a simple maxim “focus on the so called furthest users first”. We believe then you will inherently design a better service for everyone where more of the consequences will have been considered.It is now time to give the assets we have created to organisations that have the reach and resources to take them to scale. As a small, independent charity hustling for funding we would never have been able to continue the work in the same way they can..... There is also a power to stopping. It is important to question the best structure for creating the impact you want to see. There are now many more people working on responsible tech and collaborating is definitely more vital than ever.

This is one of the things I learned:

|

| https://twitter.com/hondanhon/status/1266422835389411329 |

|

| https://twitter.com/CassieRobinson/status/1264846505900457984 |

It's been a loud couple of weeks in outrage terms in the UK, especially on social media, but a couple of things stood out for me as particularly insightful. Firstly Lilian Edwards:

|

| https://twitter.com/lilianedwards/status/1264867607691300864 |

|

| https://twitter.com/davidbent/status/1264846386853482497 |

|

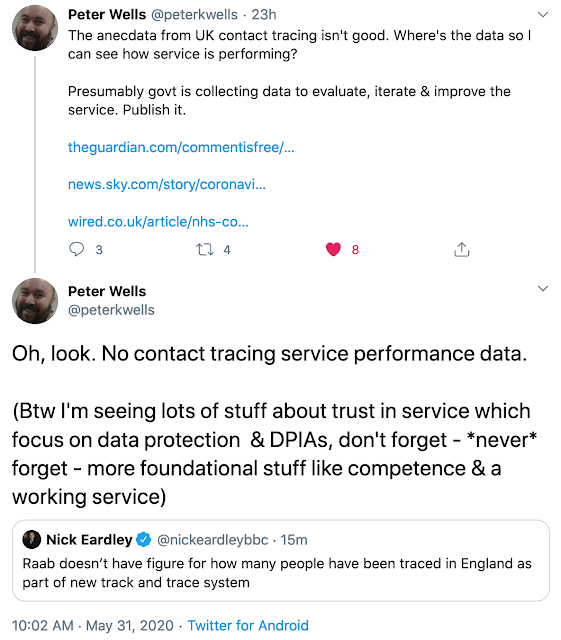

| https://twitter.com/peterkwells/status/1267018493406466049 |

All the strange things around the pandemic are playing havoc with shiny machine learning systems. Turns out they are kind of brittle! And you need humans tending them and adjusting them. MIT Tech Review:

Machine-learning models are designed to respond to changes. But most are also fragile; they perform badly when input data differs too much from the data they were trained on. It is a mistake to assume you can set up an AI system and walk away...

The current crisis has also shown that things can get worse than the fairly vanilla worst-case scenarios included in training sets. ....

As Amazon and the 2.5 million third-party sellers it supports struggle to meet demand, it is making tiny tweaks to its algorithms to help spread the load.

Most Amazon sellers rely on Amazon to fulfill their orders. Sellers store their items in an Amazon warehouse and Amazon takes care of all the logistics, delivering to people’s homes and handling returns. It then promotes sellers whose orders it fulfills itself. For example, if you search for a specific item, such as a Nintendo Switch, the result that appears at the top, next to the prominent “Add to Basket” button, is more likely to be from a vendor that uses Amazon’s logistics than one that doesn’t.

But in the last few weeks Amazon has flipped that around, says Cline. To ease demand on its own warehouses, its algorithms now appear more likely to promote sellers that handle their own deliveries.

|

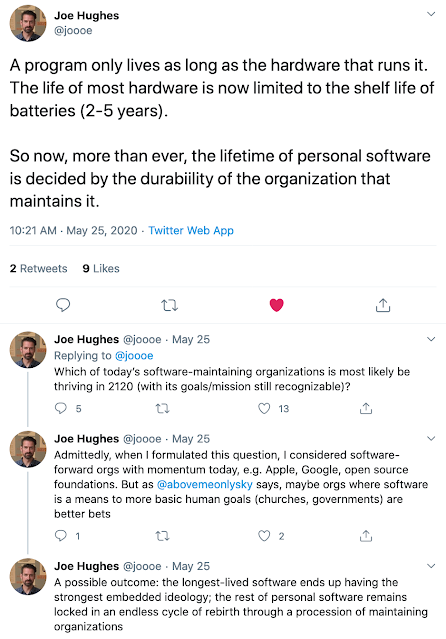

| https://twitter.com/joooe/status/1264849043622150145 |

|

| https://uncertaintymindset.substack.com/p/15-maintenance-by-design |

The most common way to think about maintenance is as a process of finding and fixing broken stuff—maintenance as the routinized search for problems. This allows many small fixes (easier and usually cheaper) instead of a big one (harder, requiring more downtime, more expensive). Maintenance at the woodshop was largely of this type: aimed at catching and fixing what was broken.

But there are at least three other ways to think about maintenance.

The first goes beyond merely fixing what’s found to be broken or about to break—maintenance as surveying what is suboptimal and improvable by being rebuilt. Refactoring code is a common example. If you do it right, nothing about how the service works externally changes. Internally, though, duct tape and baling wire is torn away and jerry-rigged bullshit is replaced. Things run cleaner, cooler, less buggily, and are better documented.

One more step beyond that is thinking of maintenance as a way to trigger unexpected ways of looking closely at a complex system—maintenance as investment in nonparameterized system awareness. A daily yoga practice is a form of maintenance, as is a weekly stand-up project team status meeting, or a quarterly board meeting for a startup. Doing the same thing at a regular interval provides opportunities to recognize when the system is beginning to fray in ways that simple problem-finding wouldn’t catch.

...But the highest form of maintenance is designing whole systems to require and enable meaningful attention when their operation conditions change—maintenance by design as whole system design for environmental perception and response. ... Maintenance by design means building systems (individuals, teams, organizations, supersystems) to intentionally be sensitive to change, to display the effect of change transparently, and to be malleable in response to that effect.In wheat terms:

A population wheatfield has a huge variety—hundreds of different kinds—of wheat; a conventional wheatfield will have a single variety of wheat growing in it.(I don't have much other food-related things this week, but the fencing went up at CoFarm and there's also now water on site, and water stuff is back on my mind again alongside food as a resilience issue not enough people are working on. It's very dry here, now. At other times we can expect too much water (flooding) not to mention drainage and waste water handling. Who is doing good, thoughtful work about local water systems at the moment?)

A diverse wheat population embodies some qualities of maintenance by design. It is highly sensitive to the growing environment: soil and weather. The specifics of the soil in which it is grown and the weather during that growing season will determine which of the wheats in the population will do better and which will do less well. The same starting wheat population will look different and produce differently in each field in which it is planted, and each field will look different and produce differently each year.

And though the weather might not be predictable, the genetic diversity of the wheats in the population buffer against that automagically: each type of wheats simply grows better or worse depending on how the weather is at any particular moment during the season.

As a result, one eminent developer of wheat populations in the UK tells me, population wheat fields aren’t prone to complete failure like monoculture wheat fields can be—in fact, that their yields are relatively stable from year to year despite dramatically different growing conditions.

Vaughn goes on:

Maintenance by design makes systems less—not more—fragile. By making the system more susceptible to maintenance, it forces the other three kinds of lower-level maintenance to happen. By making the system easier and cheaper to adjust, it allows the other three kinds of maintenance to make adaptive changes. Maintenance by design makes systems antifragile by giving them enhanced environmental perception and enhanced adaptation ability.

.... Maintenance by design has at least two principles:

1. Design the system so it shows clearly and swiftly how unexpected changes in the environment affect it without becoming incapacitated. ...

2. Design the system so it can be easily and undisruptively modified to respond to unexpected system behavior. ....

Teams in organizations: A project team working on an ultra-high-stakes, do-or-die product launch, with extremely high expectations imposed on it from top management. The launch must hit on the specified date, or else there will be hell to pay—so project management and interdependencies are tightly controlled. There is no possibility of presenting rough work in progress for low-stakes feedback—only polished, perfect product will do. Such a team is almost definitionally unable to see new and disconfirming information and make the micro-adjustments to accommodate it, even if these adjustments are what’s likely to make the team successful.This seems strangely familiar.

Unfortunately, though maintenance by design is self-evidently crucial for the world we live in today, we seem to barely invest in it at all.Isaac Wilks writes in response to Marc Andreesson's "build" piece - I'm just getting to it late. (I noted some other responses back here.)

It’s like some kind of weird cognitive disorder: most people love and cannot resist building (and being) these kinds of highly efficient, superoptimized systems which are ultimately fragile to unexpected change.

Those who resist may survive and prosper.

If we want to succeed in rebuilding the nation, we will need not just the destruction of existing barriers but the construction of positive political goals. In this light, Andreessen’s answer to the question of politics is quite strange. What does it mean to “separate the imperative to build these things from ideology and politics”? One can imagine Bay Area tech entrepreneurs nodding along to this essay, wishing that politics and the pesky state would just leave them alone to BUILD. This would be a fatal mistake.

To be sure, we must circumvent our current political paradigm. Yet this is not a separation from politics qua politics—it is politics. Building a new world is the most political question imaginable.

.... Building means founding new companies and forging new industry, but it also means building state capacity and creating functional mediating institutions for labor. Reconstructing the better part of an industrial society will take decades; and with our present white-collar workforce left utterly directionless, inflated by elite overproduction, and medicated at world-historic levels, sending a million students to Harvard will not, as Andreessen suggests, help spur technological progress. Rather, it is the regeneration of practically grounded trade schools and state-backed coordination that is needed to retrain a productive workforce.

... What exactly is Andreessen’s end? The thumbnail for Andreessen’s essay (an Adobe stock image entitled “Fantasy city with metallic structures for futuristic backgrounds”) shows a futuristic cityscape that, to put it diplomatically, looks like a forest of Gillette razors. It does not appear to be a place where life happens. It is not what living in a society looks like.

Everyone is in crisis. I want to recognize that at the outset. Some crises may be deeper, more long lasting; some may be hidden, unspoken, unspeakable; some might seem minor, but loom monstrously; some may be ongoing; some may be sudden. Some might seem surmountable, but roar back into renewed disaster. Few of these will be resolved anytime soon.Audrey notes the many forms of crisis: personal crisis, medical crisis, mental health crisis, financial crisis, political crisis, institutional crisis, societal crisis, etc. Highlights mine:

Audrey quotes Mario Savio's famous speech in 1964 on the steps of Sproul Hall at UC Berkeley:If there is one message that I want to get across to you today, it is that we must ground our efforts to plan for the fall — hell, for the future — in humanity, compassion, and care. And we cannot confuse the need to do the hard work to set institutions on a new course of greater humanity with the push for an expanded educational machinery. We have to refuse and refute those who argue that more surveillance and more automation is how we tackle this crisis, that more surveillance and AI is how we care.... Perhaps it's less that the machine can or might fool us, and more that, when we consider the question "can a machine think" today, our definition of thinking has become utterly mechanistic — and that definition has permeated our institutional beliefs and practices. It is the antithesis of what Kathleen Fitzpatrick has called for in her book Generous Thinking — what she describes as "a mode of engagement that emphasizes listening over speaking, community over individualism, collaboration over competition, and lingering with ideas that are in front of us rather than continually pressing forward to where we want to go." Generous thinking is something a machine cannot do. Indeed it is more than just an intellectual endeavor; it is a political action that might take scholarly inquiry in the opposite direction of technocratic thought and rule. "We have," as Joseph Weizenbaum wrote, "permitted technological metaphors… and technique itself to so thoroughly pervade our thought processes that we have finally abdicated to technology the very duty to formulate questions."... Indeed, our educational institutions, particularly at the university level, have never really cared about caring at all. And perhaps students do not care that the machines do not really care because they do not expect to be cared for by their teachers, by their schools. "We expect more from technology and less from each other," as Sherry Turkle has observed. Caring is a vulnerability, a political liability, a weakness. It's hard work. And in academia, it's not rewarded.

... But what I do mean is that we need to resist this impulse to have the machines dictate what we do, the shape and place of how we teach and trust and love. We need to do a better job caring for one another — emotionally, sure, but also politically. We need to recognize how disproportionate affective labor already is in our institutions, how disproportionate that work will be in the future. We need to agitate for space and compensation for it, not outsource care to analytics, AI, and surveillance.

There's a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part! You can't even passively take part! And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels ... upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to make it stop! And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!

So when I think about local delivery, this is where the rubber hits the road for all of this e-commerce stuff. Because it’s necessarily physical, it’s the sole opportunity to be face to face. But delivery, when commoditised and industrialised, also seems to be where things go badly wrong, from delivery drivers bearing the risk of whole corporations to food delivery “independent contractors” barely able to make minimum wage, and being stiffed for tips.

The big question:

Corporations and startups will inevitably move hard into the last mile delivery space. How do we make sure it’s not shit?

It’s going be…

- Boston Dynamics robot dogs delivering parcels

- Some kind of unholy FedEx-goes-local or white label Uber Eats, making people sweat to earn less than minimum wage

- or… something else? What it is? ...

I can imagine a utopian neighbourhood of cheery teenagers on their bikes earning pocket money by delivering my veg box and fancy cheese ordered via Facebook Messenger, and me tipping an extra shilling because I recognise them from last week. But this isn’t 1955 plus social media.

So what is it? How do we make sure it isn’t awful?

On WidenMyPath, you can indicate where pedestrian or cycle facilities need improvement. It's a project from CycleStreets.

Dan Hon says:

we need a Consumer Reports for Government Services, so if you’re interested in this, please get in touch. I am specifically looking for funders (doesn’t matter what kind! Institutional is fine!) BECAUSE THIS IS SOMETHING THAT IS WORTH INVESTING IN. I am absolutely livid about the expectation that something like this should be started on a volunteer basis first. I mean, have you looked outside? Putting this together is actual work, and if you rely on people who are able to volunteer their time, then… well, you’re being a bit short-sighted in your pool and running the risk of not making sure you’re able to serve the general population, i.e.: everyone.

I swear to god, if I get a single response like “Oh, this totally sounds worth it, put together a demo or see if you can get it going with some volunteers” I’m pretty much ready to name and shame. Now I’m really angry about the general western malaise and reluctance to invest in common infrastructural services. I mean, yes, someone else should be paying for it, but if you could be paying for it and getting it started, then…

Language is the operating system of organizations. It’s the working memory, the interface between teams and the process for storing and embedding long term memories.Tom quotes Noah Brier:

I’m convinced that writing is a key skill for leaders inside organizations - to be able to clearly and compellingly outline a vision and to direct attention on a regular basis.

the “skills transfer gap” ... is the one between where a skill is learned and where it is practiced, and can be the deciding factor on whether someone actually internalizes something.I am very bad at learning things if I don't get to practice them in a real setting at the same time.

Tom also quotes an interview about Automattic:

One thing that that really stood out to me about being at Automattic was that internal blogging system. ... this idea that teams would every day summarize what they were working on and the problems they encountered, the discussions they had and this idea that it became a cultural norm at Automattic where every day you start work by reading the [posts] and seeing what was going on, and I actually felt that despite the fact I was in Taiwan in a different time zone than a lot of people at Automattic, I felt like I knew more about what was happening at Automattic than I did when I was going into an office every day at other jobs.I enjoyed Chatting with Glue - a graphical exploration of conversational form - looking at both the spoken word and digital. How could online chat be better - more useful - more supportive of ideas shuffling and interactive and evolving?

....I think every company needs an equivalent of it, regardless of what’s powering it. It provides transparency versus an email chain where everything’s private, it’s locked up in someone’s box. If someone leaves, it’s all gone.

iFixit have released a great set of information about repairing medical devices, after a huge volunteer effort.

The volunteer and small scale PPE manufacturing work seems to be tailing off now; projects have ended, groups are standing down. There's an awareness that it might all be needed for a second wave, but the pressure has gone as immediate needs in healthcare are met and to some (unclear) extent also those in social care.

When will the health toll of isolation, unemployment or delayed surgery outweigh that caused directly by COVID-19? What are the implications for next year’s supplies of staple foods or of higher levels of long-term disability? How quickly can vaccine manufacture be scaled up? What release-from-lockdown strategies are behaviourally and hence politically feasible? Can national governments negotiate with each other to arrive at cooperative, mutually beneficial policies? What can international agencies do to encourage this when geopolitical tensions are rising?Addressing these questions requires collaboration across many disciplines to synthesize new findings with old — fast. It’s time to deliver on the benefits of public investment in research..... The courage to step cautiously into other domains must be welcomed. Economists are notoriously less likely than other social scientists to look outside their own discipline, and medical and natural scientists are not accustomed to looking to the social sciences for insight. The pandemic is changing all that. It has become obvious that the search for viable exit strategies needs biomedical science, epidemiology, public health, behavioural and social psychology, engineering, economics, law, ethics, international relations and political science. Without contributions from all these, navigating toward less-than-disastrous outcomes for well-being — human and planetary — will be impossible.... I am concerned that government ministers and officials are having to judge for themselves — at a time when they are massively overstretched and under pressure — how to combine insights from various disciplines. Some COVID-19 advisory groups, such as that of the UK government, have too narrow a range of experience, excellent as the individual members might be. This challenge, like other global challenges looming, is the moment for the research community to prioritize synthesizing knowledge.Sadly, academic incentives work against people who are brave enough to cross into another discipline’s territory. Career, funding and publishing structures reward research into small, narrow questions, when the world has big, complex problems. Forbidding argot is prized; accessibility is viewed with suspicion.