Weeknotes: online/physical spaces, arts, labour, ethics

Starting with digital miscellany:

Bruce Schneier is using Zoom (although the comments are not happy about this, in the main). All security is trade-offs.

Really just for the headline, because there are no surprises here: Three things in life are certain: Death, taxes, and cloud-based IoT gear bricked by vendors. Looking at you, Belkin. Farewell Wemo cams.

The Open source hardware user group (OSHUG) has been going for ten years, or thereabouts. Thanks Andrew Back for writing up some of the history - a lot of familiar faces and projects there!

You can now get a Fairphone with an alternative OS (/e/OS). There's a good write up on Ars.

OPEN.coop's online programming in lieu of the usual annual event included a webinar from the denizens of the Digital Life Collective. It was good to see many familiar faces, and to hear where things have got to with "collaboration as a service." Still a slightly overwhelming range of metaphors and structures, but nice to see some actual take up with a variety of groups using different bits of the system (also showing that you don't need to include all of the 'patterns').

A long article in the Atlantic (originally via Jon Crowcroft) about how confusing the pandemic is, in multiple ways. This particular bit, not particularly representative of the rest of the article, struck me:

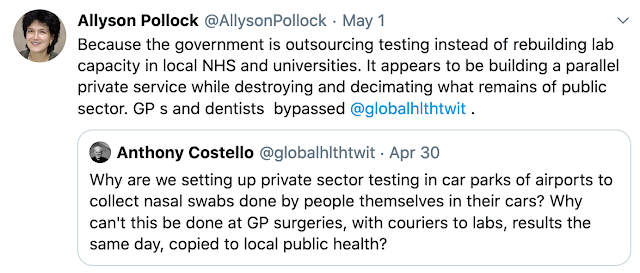

The situation as regards testing is something I've not been paying much attention to thus far, but eg this tweet from Allyson Pollock is not encouraging.

There still seems a lot to do, day to day, and Dayna Tortorici notes It really would be a silver lining if we emerged from this pandemic with a better (actual) sense of the value of "reproductive labor": the housework, cooking, child care, elder care, etc—shouldered disproportionately by women—that keeps the paid labor force intact. (Twitter thread) Reproductive labor includes ensuring the workforce outside the home are able to function each day, too.

Deepa Iyer describes a variety of social change roles in response to crisis. A useful way of thinking about different contributions, and there's a guide for reflection linked too.

Emanuel Moss and Jacob Metcalf at Data&Society write about why ethics is "too big a word" for the tech industry.

I was chatting with a friend, who is home alone at this time, about how her only interactions with people not on screens are now through a retail lens. She only speaks with shop keepers face to face. There are no opportunities to speak with people who are not in retail - no carefully distant librarian or anything else - and so ends up buying more food and drink.

This piece from Drew Austin has a number of good points but particularly struck me in this light:

Rebel botanists are using chalk to name forgotten flora (apparently chalking pavements is illegal in the UK). "Botanical chalking" is a lovely idea.

I particularly liked p9-11 of the curiosity toolkit from the Pedestrian's Society of Space and Time (Helen Tseng). HT Nadia Eghbal.

Tom Critchlow's post introducing the Yak Collective talks about sensemaking in uncertain environments, and I love the diagram setting out the idea of "Indie wisdom". We all need more wisdom, and this is a particular kind I feel an affinity with. I also like the bit in the example of Collective narratives - Companies used to operating in “strategy cultures” will increasingly find it hard to keep up—media flows faster than their OODA [observe - orient - decide - act] loop can keep up.

The Collective have a nice slide deck / report out about how to do strategy in a more uncertain, post-pandemic world, which includes a lot of useful ideas.

The power might go out on Friday, warns the National Grid, because of super low demand.

Bruce Schneier is using Zoom (although the comments are not happy about this, in the main). All security is trade-offs.

Really just for the headline, because there are no surprises here: Three things in life are certain: Death, taxes, and cloud-based IoT gear bricked by vendors. Looking at you, Belkin. Farewell Wemo cams.

The Open source hardware user group (OSHUG) has been going for ten years, or thereabouts. Thanks Andrew Back for writing up some of the history - a lot of familiar faces and projects there!

You can now get a Fairphone with an alternative OS (/e/OS). There's a good write up on Ars.

OPEN.coop's online programming in lieu of the usual annual event included a webinar from the denizens of the Digital Life Collective. It was good to see many familiar faces, and to hear where things have got to with "collaboration as a service." Still a slightly overwhelming range of metaphors and structures, but nice to see some actual take up with a variety of groups using different bits of the system (also showing that you don't need to include all of the 'patterns').

A long article in the Atlantic (originally via Jon Crowcroft) about how confusing the pandemic is, in multiple ways. This particular bit, not particularly representative of the rest of the article, struck me:

The scientific discussion of the Santa Clara study might seem ferocious to an outsider, but it is fairly typical for academia. Yet such debates might once have played out over months. Now they are occurring over days—and in full public view. Epidemiologists who are used to interacting with only their peers are racking up followers on Twitter. They have suddenly been thrust into political disputes. “People from partisan media outlets find this stuff and use a single study as a cudgel to beat the other side,” Bergstrom says. “The climate-change people are used to it, but we epidemiologists are not.”Richard Horton in the Lancet on how this is a life and an inequality crisis, not a health crisis

It is our task to resist the biologicalisation of this disease and instead to insist on a social and political critique of COVID-19. It is our task to understand what this disease means to the lives of those it has afflicted and to use that understanding not only to change our perspective on the world but also to change the world itself.The FT describes the UK PPE situation for health and social care, including a great timeline of how policy has shifted.

The situation as regards testing is something I've not been paying much attention to thus far, but eg this tweet from Allyson Pollock is not encouraging.

|

| https://twitter.com/AllysonPollock/status/1256112517291655168 |

Deepa Iyer describes a variety of social change roles in response to crisis. A useful way of thinking about different contributions, and there's a guide for reflection linked too.

Emanuel Moss and Jacob Metcalf at Data&Society write about why ethics is "too big a word" for the tech industry.

The adjective ‘ethical’ can describe both an outcome, a process, or a set of values, any of which has different connotations from a technologist’s point of view. An outcome might consist of a cloud services company declining a contract with an abusive government or agency, or equalizing error rates across protected classes in an automated hiring system. A rigorously ethical process can look like a committee of stakeholders convening to develop a plan for addressing potential harms of a new product or a review team analyzing an engineering requirements document. Values describe states’, humans’ (or any moral being’s) desires, such as beauty, justice, or wealth. Ethical values are those values that are most pertinent to assessing the moral correctness of the decisions we face, and in tech contexts values such as transparency, equity, fairness, and privacy are often pertinent.(We chose not to talk about ethics much at Doteveryone, instead focussing on responsibility as a more straightforward and comprehensible idea, especially for industry. In checking recently I found we didn't really write up this decision at the time, or in this 2018 reflection, or in Tech Transformed, the programme to support businesses and other organisations building technology, which resulted from our earlier work.)

...We suggest that in the best case, ethics inside of technology companies consists of using robust and well-managed ethical processes to align collaboratively-determined ethical outcomes with the organization’s and commonly-held ethical values. This is not an easy task, even when there are clear guidelines and best-practices for producing straightforward products or services.

...But outside tech companies, ethics looks very different: the legitimacy of tech companies, their business models, and their socio-political power are read through the lens of moral justice. As our colleague danah boyd recently observed:

“How does a company have values beyond profit for shareholders? Many of the folks on the outside aren’t even talking about trade-offs and values. They want justice. Ethics tends to encompass all of this … from the world of legal risk, all the way to justice. As a result, the people on the outside are not at all satisfied by the ideas we’re going to get from compliance… We’re going to have such contested challenges around this because we don’t know how to articulate values within this form of capitalism.”

... To make sense of these complexly polysemous meanings of “ethics” in tech, we have identified four overlapping meanings of the word “ethics” among those who use the term most forcefully:

- Moral justice

- Corporate values

- Legal risk

- Compliance

I was chatting with a friend, who is home alone at this time, about how her only interactions with people not on screens are now through a retail lens. She only speaks with shop keepers face to face. There are no opportunities to speak with people who are not in retail - no carefully distant librarian or anything else - and so ends up buying more food and drink.

This piece from Drew Austin has a number of good points but particularly struck me in this light:

The discourse around “reopening the economy” has fascinated me for precisely this reason, as it accidentally admits that we have nothing to reopen but the economy, which basically encompasses everything.

...

As the American urban environment has grown increasing privatized, consumption has been the primary way to engage with it. Spaces where we can do anything other than eat, drink, shop, or exercise have diminished, swallowed up by what Koolhaas calls junkspace.

... Thankfully, the physical domain is subject to more inertia than its digital counterpart, and is harder to push toward full monetization. ... In New York, the parts of the city that aren’t defined by consumption are specifically what’s still open. Junkspace is closed and we can only occupy the interstitial spaces between establishments searchable on Yelp. The exterior urban environment has unintentionally decoupled from the economy, and to spend time outdoors in these conditions is to re-establish a more direct relationship to space that normally extracts value from us at every turn. The primary way we experience much of that space under normal circumstances is by passing through it on the way to somewhere else; now, momentarily, that “somewhere else” isn’t available. The official act of reopening cities will signify the reintegration of space and the economy, but when that finally happens, hopefully, we’ll remember what we learned during this time—that the two aren’t as inseparable as they seem.This references Drew's longer form piece here:

This new sensitivity to space strikes a jarring contrast with an attitude that had been emerging before the pandemic, which regarded space as an annoying set of limitations that could be overcome by digital technology. A recent spammy promoted tweet from a generic-looking tech-industry thought leader perhaps put it best: Technology could “turn the real world into a clickable, searchable, data-infused experience.” From this perspective, the physical world appears as a cumbersome, geography-constrained interface that the internet could streamline, making activities like talking, shopping, banking, and sharing photos with friends more convenient and, for tech companies themselves, more profitable as space ceases to limit scale.The best experiences I've had online don't aim to recreate in-person things, but to do something different. Sometimes this is with people I know, sometimes not. Coney's remote socials have been one highlight.

... Consider, for example, the video-conferencing platform Zoom. During the quarantine’s first few weeks, it emerged as a flexible (albeit insecure) tool for conducting interactions that could no longer happen face to face, rapidly expanding beyond its established domain of business meetings to accommodate gatherings ranging from happy hours to dinner parties to dates. But rather than providing support for adjacent activities, as an app like Slack does for office work, Zoom replaces those activities altogether. In other words, users experience Zoom more as a stultified form of virtual reality than an augmented one, because it feels as though there is very little off-screen reality available to augment right now.

Instead of supporting more robust forms of interpersonal interaction by adding layers of information or creating dynamics that aren’t possible in physical space, as video games and social media do, Zoom merely simulates in-person interactions in two-dimensional space while we wait for life to return to “normal.” Live events replicated via Zoom feel less like convenient alternatives than inferior and sometimes tedious simulacra. Instead of the full sensory immersion that we experience at a party, concert, or even a meeting, we have flat representations in browser tabs or apps, competing with the rest of the “content” delivered by the same screens.

In How to Do Nothing, Jenny Odell makes an eloquent case for the importance of place as a site of non-transactional human relations. As an example, she describes how, for many, public transportation is “the last non-transactional space in which we are regularly thrown together with a diverse set of strangers, all of whom have different destinations for different reasons.”Via Rachel Drury, a Robert Hewison piece about the need to reimagine the infrastructure of the arts:

It was understood that artists, writers, composers, directors and performers employed in the significantly titled “not-for-profit” sector were in fact creating profits, directly through copyrightable ideas and images which can then be commercially exploited, and indirectly in terms of the cultural consumption they generate in the form of local and international tourism. The argument was enthusiastically taken up by declining cities like Glasgow, which badly needed an image makeover. Liverpool has similarly benefited from the “City of Culture” process.

There are a number of problems with this: it is doubtful that Glasgow’s “Merchant City” has done much for Easterhouse, or that the virtual privatisation of Liverpool city centre has benefitted Knowsley. Arguably, the money could have been better spent on renewing the social infrastructure rather than creating a fashionable façade.

But the consequence of arguing for the economic importance of the arts—even when it is in one’s own interest—is that the arts become more and more a commodity like any other. Driven by the neo-liberal principles that for the past 40 years have framed thinking about the economy as a whole, cultural institutions that were consciously set up without profit in mind have been made to seek ever greater profits. Because their public support has indeed been progressively driven down as a proportion of their turnover, arts organisations have had to do deals with ethically and environmentally dubious commercial sponsors. For the same reason, museums have become shopping malls, theatres and concert halls have put ticket prices out of the reach of many of the people that public funding was intended to encourage to participate.

... the arts are not, ultimately, a commodity. They are an offering. They offer meanings that exist outside the cash nexus. They offer delight, they offer hope, they offer consolation. As I have long argued, there is a difference between value in exchange and value in use, between cash value and cultural value. We have to think of the arts as part of the public realm, that space where private and public interests meet and where their conflicts can be resolved, where the local can find accommodation with the national, and where there are institutions that are not driven solely by the profit motive, but by the idea of a greater public good.

... This is an opportunity to reimagine the infrastructure of the arts, especially at the local level, away from London and Whitehall. We need to think about the 80% or more of the population who are not regular enjoyers of what the publicly funded arts have to offer. We must create the circumstances where arts organisations can grow until they can stand on their own two feet, and then not be burdened with the expectation of extraneous outcomes and spurious metrics. We should worry less about the creative economy, and rebuild the public realm. From the ground up.Willow Brugh is organising RecoveryCon to "start thinking about how we can make the world better as we move from pandemic and quarantine into whatever comes next." RFP open until May 16th.

Rebel botanists are using chalk to name forgotten flora (apparently chalking pavements is illegal in the UK). "Botanical chalking" is a lovely idea.

I particularly liked p9-11 of the curiosity toolkit from the Pedestrian's Society of Space and Time (Helen Tseng). HT Nadia Eghbal.

|

| http://helentseng.com/p-s-s-t |

Tom Critchlow's post introducing the Yak Collective talks about sensemaking in uncertain environments, and I love the diagram setting out the idea of "Indie wisdom". We all need more wisdom, and this is a particular kind I feel an affinity with. I also like the bit in the example of Collective narratives - Companies used to operating in “strategy cultures” will increasingly find it hard to keep up—media flows faster than their OODA [observe - orient - decide - act] loop can keep up.

The Collective have a nice slide deck / report out about how to do strategy in a more uncertain, post-pandemic world, which includes a lot of useful ideas.

The power might go out on Friday, warns the National Grid, because of super low demand.