Weeknotes: rebuilding/demolishing, procurement, supply chains, friendship

Sheila Jasanoff on the pandemic, including the neglect of social sciences, the side effects on vulnerable populations, etc:

A friend in the Netherlands told me about their shortage of intensive care units. Germany has one of the highest ratios of intensive-care beds-to-population of Northern European countries. They’re economically very comparable countries, so why the lower percentage of ICUs in the Netherlands than Germany? My intuition is that the Dutch have a much more stringent idea of when ICUs are allowed to be used—that is, their social definition of what patients should get ICUs seems to be different from Germany’s. What is a life worth saving? When do we declare that further measures should not be undertaken, when do we not call it triage but a sensible medical decision? These are cross-cultural questions that we haven’t really thought about.Pandemic bonds may not pay out to help developing nations, because specific criteria haven't been met (and perhaps never would be met during the early phases of an epidemic when financial support could reduce impact). (From FT Moral Money, paywall) Clare Wenham from LSE says “They’re written by risk modellers to ensure they’re lucrative for the private sector rather than protecting people who are suffering a pandemic.”

....

Science has become as powerful as it has because it has adopted the idea of peer review—that you don’t trust one person, you trust one person’s judgment, because it’s been questioned by other people. Modern science has specialized, and peer review is pretty good when it functions inside a narrow community. Peer review is not good when you need to confront different bodies of knowledge with and against each other. Someone who understands the dynamics of what happens inside a family when you’re cooped up together for week upon week—that person is not going to tell you very much about how a virus acts inside a body, or how quickly contagion spreads if you don’t self-isolate.

....

I would like to see a society that emerges from this period of crisis with a heightened understanding of what it means to individualize things that were once seen as collective and social. Maybe this concentrated shock will finally be enough to make people sit up and say, “Everything has to have its limits, and we cannot simply dissolve what was public and collective into individual and solitary responsibilities without paying a lot of penalties for that.” My political preferences are for a society in which solidarity means more, in which there is more shared infrastructure, where in the context of a crisis we do not have to depend only on our wits and whether we have enough land and enough seed and enough water and fertilizer to create a victory garden of our own.

The Care workers fund is raising funds for crisis grants for carers.

A detailed study of the economic impact of the pandemic on cities and towns in the UK from the Tortoise. Some nice visualisations and some scary figures; it seems likely that shops which cater for very local consumers - living less than a mile away - are doing best. (Thanks Rachel Coldicutt for sharing this.)

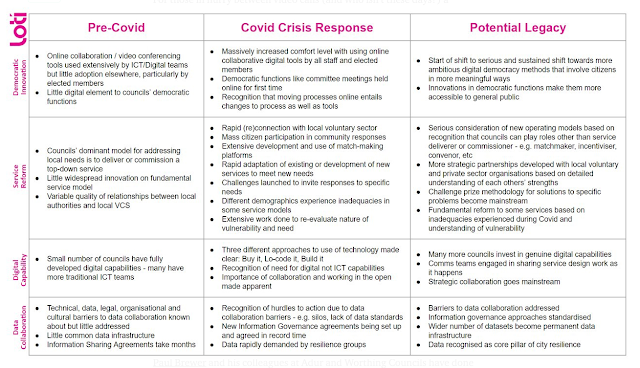

Via Naomi Turner, a great article by Eddie Copeland about local authorities and digital tools - what changes have happened and what they might mean long term. It's mostly about relationships and pragmatism, not about tech, unsurprisingly. The summary:

|

| from https://medium.com/loti/beyond-the-crisis-how-local-government-can-build-a-positive-legacy-after-covid-3ac6e3d32a24 - London Office of Technology and Innovation |

Who has time to build a better future? Various people have been responding to Marc Andreessen's request that people get building things to fill in the critical gaps in our infrastructure (broadly interpreted).

Ben Thompson suggests that Silicon Valley is a distorting feature, both in what is possible (or not) there, and in how it sees innovation.

I agree with Andreessen that much of the software revolution is inevitable; I also agree that tech’s seeming exclusivity on innovation has also been about the online space being the one place without the inertia and regulatory capture Andreessen decries. If you are talented and ambitious, what better place to be?Ben goes on to suggest how to respond to the essay - at least, for those in the Valley and in investment:

What I also sense in Andreessen’s essay, though, is the acknowledgment that tech too has chosen the easier path. Instead of fighting inertia or regulatory capture, it has been easier to retreat to Silicon Valley, justify the massive costs of doing so by pursuing inifinite-upside outcomes predicated on zero marginal costs, which means relying almost exclusively on software as the means of innovation.

First, tech should embrace and accelerate distributed work. It makes tech more accessible to more people. ... It creates the conditions for more stable companies that can take on less risky yet still necessary opportunities that may throw off a nice dividend instead of an IPO....So there are things you can do if you wield lots of capital as an investor. But the essay seems to suggest others should be taking action, too. Vicky Boykis writes:

Second, invest in real-world companies that differentiate investment in hardware with software. This hardware could be machines for factories, or factories themselves; it could be new types of transportation, or defense systems. The possibilties, at least once you let go of the requirement for 90% gross margins, are endless.

Third — and related to both of the above — figure out an investing model that is suited to outcomes that have a higher liklihood of success along with a lower upside. This is truly the most important piece — and where Andreessen, given his position, can make the most impact. Andreessen Horowitz has thought more about how to change venture capital than anyone else, but the fundamental constraint has remained the assumption of high costs, high risk, and grand slam outcomes. We should keep that model, but surely there is room for another?

... The changes that are necessary in America must go beyond one venture capitalist, or even the entire tech industry. The idea that too much regulation has made tech the only place where innovation is possible is one that must be grappled with, and fixed.

...We need to figure out how to fix Wisconsin, not flee from it. We need to figure out how to build real businesses that build real things, not virtualize everything. And we need to start fighting for not just infinite upside, but the sort of minute changes in cities, states, and nations that will make it possible to build the future.

...I left the essay unclear as to what Marc wanted me to do about any of the problems he pointed out. Here are some of the things he proposed in the essay:

What can I, personally, do, in the .3 hours of time I have left in the day, that counts as building?

- Building more universities

- Building more futuristic cities

- Developing advances in education

- Building more factories in America

- Developing and deploying delivery drones

- Building better housing

|

| https://twitter.com/vboykis/status/1252191107099877378 |

Vicky goes on to point out that whilst we may be able to find the time to sew a mask or deliver groceries to someone, these small actions do not add up to the large changes Marc calls for.

We can fight against small injustices. But there are much larger issues at hand: corporations manipulating laws for their own profits at the expense of small businesses. Private equity. Lobbying. How do we fight to build against that?

... finally, there is the system that Andreessen himself now plays in: venture capital in technology, which has sought to grow, make money and eat the world, at the expense of everything else. You could argue that A16Z portfolio companies like Slack, Digital Ocean, IFTTT, and Instacart have brought intrinsic benefits to humanity. And they have. Instacart provides all my groceries these days. I can work remotely thanks to Slack and, as a result of Slack, Microsoft Teams. Facebook, also an A16Z alumn, is now where many people find part-time work, facemasks, and stream live events.

But the amount of misery these companies have inflicted in their path to profitability has been enormous. Starting with the small things, like Imgur and Reddit turning into platforms that are almost unusable, to Keybase’s problems with boosting user growth by offering crypto (no doubt due in part to some encouragement from A16Z, which is all in on crypto lately) , to even one of the most treasured sites online, StackOverflow, becoming impossibly hard to keep afloat with the backpressure from VC investment demands. Instacart, as wonderful as it is, has still not delivered safety supplies or hazard pay to its drivers.Is it a complex systems problem?

The more I think about it, the more I think the real problem is not that we’re not building things. We’ve built plenty as a country - The Hoover Dam, nuclear plants, the internet, and the reputation that to come to America and live here is opportunity.She gives a number of examples of complexity in pandemic response and housing, then notes:

The problem is that, over time, we’ve actually built too much. The systems have become too big for people, as individuals, to work through.

As a result, the solutions that end up emerging in these systems are not the best answers, but the results of the individuals who are so far above all of the fluctuations that they know how to manipulate these economic and political systems in their favor.It's OK if you are Elon Musk or Larry Ellison. Our ability as regular folk to step up and build is more limited:

Not only are we small, we’re exhausted, worried, broke, and, for some of us now, very, very sick. We might all be inspired to come out of this starting a business, but we’re coming out of this thing like out of a forced collective trauma where we pause to pick up the pieces, not pick up the phone and start making calls to governor’s offices and - God forbid - start making dashboards.

... So while the readers truly inspired by “It’s Time to Build” are out there with huge construction cranes, there also needs to be a separate set of people, less noticeable but just as important, holding chisels, to chip away at the systems we’ve built - the legal hurdles, political systems, large swaths of government that are ineffective, and VC-based technologies and startups that don’t do any of the actual building but only get in its way.Which reminds me of Cassie Robinson's thinking about what we need to discard in this "great unravelling."

- We know that in the recovery and rebuilding of civil society some organisations will be left behind — this will be painful, and is there something we can do with this work that helps support that loss?

- Generally there already is, and will continue to be, a swell of grief all around us. Is there something we can do with this work to make that grief visible and more of a shared experience across civil society? Are there public, sector-wide type rituals that this work could help develop? ....

It's wonderful that Cassie has some support from the Paul Hamlyn Foundation to take forward this line of work :)

- Whilst some loss will be painful, there will be things we want to leave behind. Can we use this work to design how to do that well? This feels most similar to my original proposal. This might include behaviours and beliefs we want to leave behind too, not just organisations.

- Similarly, there will be organisations that whilst painful to lose, we may also recognise have had their time — were flailing in some way already, perhaps because their place in the world didn’t quite fit anymore. Could we use this work to create space for people to come to terms with loss, to find acceptance, and most importantly to help build a legacy from the work they’ve done?

A thread on food security from Elle Dodd, looking at what might happen in the UK in the future where imports may be more scarce or expensive. Like Elle, the more I learn about this the more I worry, too. CoFarm work has slowed down for obvious reasons; we got a grant application in last week for support activities which we can work on remotely. There's so much more to do though.

Via Francis Irving, a terrific blog about hosting an online party. Clearly this was a large scale endeavour compared to what most of us might attempt, but it's full of useful ideas which are just as useful for small social events. How you use breakout spaces, designing for different moods and types of interaction through time and space, and how to make an online event a more human experience.

Cassie Robinson reposted this from Tumblr, eight years on:

|

| https://ahootingandahowling.tumblr.com/post/15256991448 |

Our food and other supply chains depend on transport. This article (via Reilly Brennan) looks at the ways long haul truckers in the US are being affected by the pandemic:

Federal regulators’ move to temporarily drop limits on how long truckers can drive, to help restock coronavirus-barren store shelves, is running squarely up against two of the most basic human needs: food and bathrooms.Let's fix procurement, says Alastair Parvin:

Ten drivers, representing those who drive for themselves, small companies, and large carriers, said in interviews that they’ve struggled over the last month to find hot meals and clean restrooms outside of truck stops throughout the continental U.S. A few long-haul drivers say they’ve resorted to scrounging for snacks at rest stops and using unsanitary port-a-potties outside pickup and delivery spots whose staff, afraid of the virus, won’t let them inside to use the bathroom.

....

However, the federal government can’t necessarily force states to keep restaurants and truck-customer bathrooms open, clean, and friendly to drivers. It’s up to states and private companies to take care of the drivers....

Drivers often can no longer use the bathroom at a customer’s site, where they pick up and drop off items, even though they have to park there sometimes for hours, several drivers said.

And yet, the Shield initiative — and many other SMEs — have found it extremely hard to get their products to where they are needed, let alone paid for. In many cases they’ve ended up finding other buyers, or giving them away and relying on donations. Where rapid deals have successfully been made by government, it seems to have mostly been with a small number of large providers, such as Dyson, McLaren F1 and Burberry, but below this scale, it seems to be much more difficult.

So what’s going wrong? While there will be lots of criticism suggesting that this is a problem of political competence or will — and perhaps some of it will be valid — I suspect there is actually a more structural problem at play here: government literally does not know how to procure from a thousand SMEs. And it certainly doesn’t know how to do it rapidly.

....What about innovative ideas, that might be expected to come from smaller or unusual sources?

The root of the ‘closed market’ problem lies in the question of what it is exactly that the government is buying. Are they buying just the product or service? Or are they also, in-effect, procuring its R&D? Are they procuring a package that involves setting up a whole new supply chain from scratch? Are they procuring finance for the product (eg, ‘Private Finance Initiative’ (PFI) contracts)? Are they outsourcing risk (eg. ‘Design & Build’ style construction contracts)? In recent decades, the answer to this question has very often been: all of the above. Outsource everything, it’s just easier that way.

The problem with bundling everything together like this is that these contracts become such huge undertakings that only big players, with an established ‘track record’ can successfully bid for them.

....

A second side-effect of these high-capital-cost-contracts is that bidders demand long contract durations to recoup their initial investment; sometimes even 10 years or more. So sure, there is a brief phase of market competition during the tendering phase, right up until the moment the signatures are put onto the contract. But at that point, the winning company (often the lowest bidder) has effectively won a 10-year monopoly. From the moment the ink hits the page, the supplier has a direct, rational incentive to minimise the quality of the product or service (think of those crumbling PFI schools), and to spend zero on innovation that would benefit the customer, society, the economy or the environment. Their professional duty is to maximise returns to their shareholders, and that means keeping the product or service as bad as they can get away with.

....

The great irony of this ‘big’ public procurement model is that government becomes so utterly dependent on these huge companies that they become ‘too big to fail’. So when they do, government ends up having to bail them out or pick up the cost anyway.

Procurement rules mean that above a certain threshold, an open tender must be put out, looking for at least three bids. At this point, one of the existing incumbent companies with a long track record can offer to deliver a terrible version of the proposal, stripped of all social, economic or environmental value (all the stuff that is difficult to account for), on terrible terms, but at a low price. Unless the original proposers can measure the immeasurable, and prove the unprovable, then the public authority must choose the cheaper of the bids. The original proposal is hijacked and taken on a race to the bottom.What can be done? Luckily the article contains a range of great ideas:

...we drafted a checklist of 15 simple but robust basic checks for any local government IT contract. It included things like a customer’s right to extract their own data at any time, and a ban on any contract longer than 2 years. We realised that if government were to make all public sector IT contracts conditional on meeting those 15 rules, government could prevent most, if not all, of the kinds of market failure we see across public sector IT every day, where government ends up paying millions for rubbish, outdated software. In other words, there is no such thing as ‘The Market’. There are many possible markets, and government has more power than it thinks it has to shape markets where it is almost impossible for them to go too far wrong. I would argue that not only does government have an opportunity to use its platform power more effectively, it in fact has a moral obligation to do so.

...

Another approach we’ve been exploring, particularly in relation to procurement of buildings, is to shift away from the practice of bundling everything together (R&D, finance, delivery, risk etc) into a massive contractural black box, and instead doing the exact opposite: breaking everything you want to buy into small, separate, predictable, transparent modules, each of which is documented for all to see, and can be procured from any (or several) of a range of suppliers at any time.

...

So what if, instead of getting suppliers to bid on price, we were to fix the price across all potential suppliers, but then invite them to outbid each other on quality or performance. In effect, to trigger a race to the top on quality and other social or economic outcomes. It’s a way of extending an open invitation to all possible suppliers, including new entrants, and saying ‘here’s the money that’s on offer, what could you do with it’?

Harry Trimble is asking for help in documenting types of bins in the UK for Govbins. You can contribute; it doesn't look like Harry is documenting what the different colours of bin mean in different areas (yet). The differences here due to decentralisation are deeply frustrating and confusing.

Hybrid products are the hardest to recycle.

Via many people, a good feature about the right to repair, and our ability to do so, featuring I think all the people engaged in repair, spare parts, campaigning, skills and more.

An astonishing note from the esteemable Internet of Shit:

|

| https://twitter.com/internetofshit/status/1252639771610034176 |

My former officemates/colleagues Jennifer Cobbe, Chris Norval and Jat Singh have written a great paper about online service supply chains - all the digital systems which make our end user experience of the internet work. It's a terrific overview of the many different systems involved, and points to implications for resilience, governance and more.

This FT article (free to read) suggests we might move to a four day workweek, with a ten day isolated 'weekend' to enable economic activity outside the home to pick up. There's a thought.

It's Earth Day. Climatestream lists many online events you could take part in.

The quest for PPE to be available to those who need it continues.

Tim Minshall has written up a brief history of how this has gone in the UK so far, which highlights the manufacturing community response in particular. Tim briefly mentions frustrations with data gathering efforts where the information seems to disappear into a black hole (all too common both at government and grassroots levels), and the need for relationships to make things work - these are not just data/automation questions. In the UK distribution wing of HelpfulEngineering, we are once more reflecting on how best to support and enhance the activities going on around the country; is sharing and maintaining information (as we are doing here for instance) the best thing, alongside making connections when we can? Should we also be supporting relationships between those who are not so well supported by other efforts - smaller scale manufacturers and care providers for instance? We're experimenting with customer support style 'ticketing' here, as this offers a more person/relationship-centred route to scale, but it's not clear if this is wanted or useful yet.

I recommend this video, showing how to think about getting involved with PPE and creating a production line, starting and thinking about scaling up from the start - a really nice intro. You might find it starts slow/obvious, stick with it :)

The use of local community specialists here - eg dental nurses who know how to sterilise gear - shows the power of building on local strengths.

There's an interesting article describing how the grey market is playing out for PPE and the risks to watch for if you are buying.

The UK's ventilator challenge was/is a mess, says the FT (paywall) - an alternative read is Peter Foster's twitter thread.

TheManufacturer has a great list of companies who are helping in the response, in varying ways.

BSI ran a webinar on PPE standards for pandemic response, which was poorly designed - we only got to relevant medical/care equipment after 40 minutes of the available hour. There's been some questions about the easement for PPE - does it only apply to sales to government and/or NHS (perhaps not to social care, for instance)?

Some standard documents are available free of charge, now, which is useful, but we're still DRMing these standards which seems to be adding unnecessary friction.

Interest in gowns is growing. The term is used to mean different things - sometimes fully waterproof, sometimes not, sometimes a labcoat or similar would suffice. It seems an easier area than some to improvise equipment for - the binbag outfits featured in social media are usually attempts at gowns - but as ever the question of how to provide these in larger quantities is perhaps the most interesting. Makerversity via SHIELD seem in the vanguard here and I look forward to what they can share.

LudoNarraCon is happening on Steam this weekend - a festival of narrative gaming, featuring games I've played a bit of (NeoCab, Mutazione), games I intend to play (Frog Detective 2!), games adjacent to games I've played (Sunless Skies), and I'm guessing games I will play. Narrative games are something I tend to think of as best for solitary play; for sociable gaming I'm on Steam, Xbox, Switch and Discord, and I'm happy to connect with folks whom I know socially on these platforms - drop me a line for my codes/usernames.