Fortnightnotes: food systems, thinking in uncertainty, being social remotely, climate stories

Theresa Marteau talked about how we are more acutely aware of the risks of obesity now. We know that small changes, such as simply increasing the proportion of healthier or more environmentally friendly food options on a menu, change behaviour. Will public policy making be bolder, following the learnings of this pandemic, or less bold?

Ottoline Leyser talked about food as an example of a complex, dynamic multi-scale system, and the tension/conflict of working in such systems with the desire for SMART goals in modern management (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-based). We do have tools for understanding them - such as agent-based modelling - but the work is in uncertainty and must be understood in that light. A large number of small changes will be the best approach, and there will be no silver bullet. This is a hard thing to communicate or sell in policy terms. The work will take a long time, and may have sudden transitions. There won't be quick results. It will take courage to make changes, and monitor how things go for a long time. The pandemic has shown some willingness to operate in uncertainty, but the media and public discourse does not recognise the lack of a single 'right thing' and that that decisions will need to change and evolve. Getting to a common desired goal is critical, so everyone can be galvanised. Identifying that goal may not be straightforward. The agriculture bill, for example, looks at public money for public good. You need consultation and consideration to identify the public goods together.

5-8% of people have a food allergy which could be life-threatening - which affects food provision, perhaps especially in public institutions (hospitals, prisons) which don't see themselves as food providers particularly, and which are operating on extremely pared down budgets.

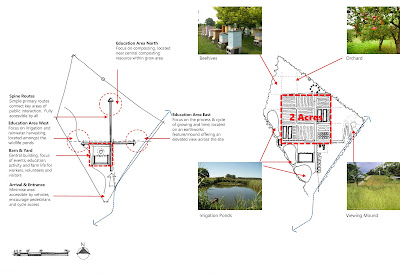

Given all of this, it was great to see progress at CoFarm Cambridge this week, with work on site and rabbit-proofing about to go in.

It doesn't look much now, but it's going to be lovely:

Her slides were fantastical and unexpected, and shaped perceptions of her talk somehow. She talked about climate science and communications, asking questions such as: how can we motivate people with language and concepts they can relate to, whilst challenging the status quo? Narratives around individual action, prosperity, and public health are often good for engaging people, but are too easily subject to co-option. The idea of a global narratives approach, thinking about things like how you motivate different people - perhaps atheists and people of faith - in different ways towards the same aims, such as forest preservation. Her examples from history of stories and practice relating to communicating pollution were unusual - it was good to go back well beyond the mid twentieth century for ideas here. Can we use traditional story plots, and a framing that works today, for climate change stories?

for more surprising fungi ecosystem explorations. Also:

Vehicle automation in particular is raising critical human factors issues which directly impact human-machine interaction and road safety. It is especially important that users of partial and semi-autonomous systems in safety-critical contexts understand the limitations of the technology, in order to ensure appropriate reliance. Studies indicate that media and marketing descriptions of vehicle automation affect user perceptions of asystem's capabilities, and later their interaction with the system. Much like “greenwashing”, the capabilities of automation are often overstated. The lack of public awareness of this issue is one of the most critical problems impacting trust calibration and the safe use of vehicle automation. Yet, it has gone unnamed and continues to affect the public understanding of the technology. Hence, the case for the use of the term “autonowashing” to describe the gap in the presentation of automation and the actual system capabilities is put forth.

Governments have no influence, or have elected to have no increasingly little (sigh) influence and input into, the technical infrastructure of a society.

Oh sure, there are areas where government have decided they want to have input, and unsurprisingly, these are issues of national security or a think-of-the-children argument.

.... Governments used to do this. They used to be involved in standard setting, and, in some respects, the U.S. government continues to do this with bodies like NIST and government also do it through quasi non-governmental bodies like ISO and so on. There are certainly areas in which government maintains the semblance of interest and participation, I mean: even stuff like clean air and environmental regulations and legislation, right?

But for some reason not in consumer technology, and part of me thinks this is a particular and strategic success by the Silicon Valley VC set who have advocated for bottom-up successful definition of standards without interference from top-down standards-setting bodies. Those bottom-up “set a standard by reflecting what’s most widely used” sure works… in some contexts.

.... If COVID-19 doesn’t illustrate the need for regulation of certain aspects of widespread technology platforms at the very least in the domain of public health, then I don’t know what help we have of an informed and cooperative policy around technology and society in the near to mid-term future.Standards, still the neglected area of how "tech" thinks about itself, and how the media sees it.

tl;dr: governments were all excited about the information age and actually did not do anything about it and now are being left behind because they’ve ceded ground to commercial development.

...how we’re in like week 3-4 of broadcast TV figuring out how to show many participants in a piece of video (you know, all those bits that have the checkerboard / celebrity squares layout of multiple participants in a video conference) and we haven’t had any interesting experimentation yet, it’s all zooming in/out of individual panels, or, I don’t know, Ken Burns Effects over video.This is very true - we need more ways to be together online. Techcrunch reviews more serendipitous chat options. Tom Critchlow has some thoughts about the design of virtual spaces - going far beyond the 'grid' of "zoom" (which seems to be the generic now for standard internet video conferencing). Or you could hold meetings as a cowboy in Read Dead Redemption [thread]. Lou Woodley helpfully and concisely reminds us that remote is strongest when the focus is asynchronous:

Where’s all the inspiration fromActually, one of the best examples is basically the acceptance of videogames leading to stuff like talk shows happening in Animal Crossing. Machinima’s time has come!

- frame-driven storytelling in comic books and graphic novels

- 2003’s Ang Lee adaptation of the Hulk

- compositing into virtual sets (although I think Have I Got News For You has done in this in the UK and it was… bad?)

- virtual conference rooms like in Demolition Man, Captain America: Winter Soldier and more

- Fortnite and so on

Similar ideas also came up in Marie Foulston's excellent talk for Watershed, which included subverting tools for work and tools for fun, and how she ran a party in a Google Spreadsheet. How can we have quiet, liminal spaces to be together online, instead of always on video? Where are the equivalents of staring out the window or at the menu in a group at a restaurant?

Marie also suggested we should talk more about the size and scale of communities (particularly when experiencing creative work). The virtual field trips of Now Play This at home were very small scale, perhaps a dozen participants, making for accessible conversations. Smaller spaces retaining time, identity, relationships in a different way to larger ones.

How do you 'onboard' people into unusual activities online? You still have this in real world experiences, like escape rooms, where there's some initial context and instructions. The spreadsheet party had a front door with tips.

Within the American neoliberal imaginary described by Foucault, all human beings can be understood as ‘human capital’. A construction worker, a taxi driver or a factory worker could all acquire skills, change their ‘brand’ or seek a new niche, where ‘profits’ can be made. But sociological reality falls short of this.The point about sympathy and humour is particularly telling.

... It’s not simply that some work can happen at home, while other forms of work can’t; it’s that some people retain the liberal status of ‘labour’, and others have the neoliberal status of ‘human capital’, even if they are not in risky or entrepreneurial positions. To be a labourer, one gets paid in exchange for units of time (hours, weeks, months). To be human capital, one can continue to draw income by virtue of those who continue to believe in you and wish to sustain a relationship with you. This includes banks … but it is also clients and other partners. The former is a cruder market relation, whereas the latter is a more moral and financial logic, that potentially produces more enduring bonds of obligation and duty.

The furlough scheme disguises the difference, but one of the divisions at work here is between those whose market value is measurable as orthodox productivity (cleaning, driving, cooking etc), and those whose market value is a more complex form of socio-economic reputation, that they can retain even while doing very little. The likely truth is that there are all manner of people in the latter category, who are unfurloughed, ‘working from home’ but doing very little work because of caring responsibilities, anxiety or because there simply isn’t work to do. And yet their employers continue to pay them, because their relation is not one of supply and demand, but of mutual belief between capitals.

...For the white collar ‘human capital’ parent, it is reasonable to explain that they will be working at less than the usual rate due to childcare, and expect full pay. For the parent who is paid to labour, there is no justification (or no currently dominant justification) for continuing to pay them for more hours than they put in.

....

The reason the Prime Minister wants others to be ‘encouraged’ back to work is because they are only valued and valuable while they are working. They don’t exist within a logic of investment and return, but one of exchange. Even if these people could do their work from home (imagine, say, a telesales assistant), they would not enjoy the same ability to integrate their work with childcare; there wouldn’t be the same levels of sympathy and humour when children disrupt their work; they are not being employed as an integrated moral-financial asset with a private life, but for the labour that they can expend in an alienating fashion.

You end up with a bunch of people repeatedly asserting that this particular crisis we now face — some 1.5 billion students in over 190 countries out of school due to the coronavirus — is "unprecedented," that schools have never before faced the challenges of widespread closures, that millions of students worldwide have never before found themselves without a school to attend.

In fact, in 2019, UNESCO estimated that 258 million children — about one in six of the school-age population — were not in school. Disease, war, natural disaster — there are many reasons why. Although we have made incredible strides in expanding access to education over the course of the past century, that access has always been unevenly distributed as are the conflicts and crises that undermine education systems and educational justice everywhere. This isn't just something that occurs "elsewhere." It happens here in California, for example. In this state, over the past three years, students have been sent home in record numbers as schools have had to close due to wildfires, shootings, and collapsing infrastructure — broken pipes, mold, lead in the water, and so on. Last year alone, some 1.2 million California students experienced emergency school closures.

Normally, “an elite packs unlimited distance into a lifetime of pampered travel, while the majority spend a bigger slice of their existence on unwanted trips,” a statement Ivan Illich made in 1973 that only became more true in the years since. With vacations and (most) commutes currently paused, domestic space gains proportional importance, but that stasis also means we’re not using much oil, and fully-loaded tankers are loitering on the open sea as the oversupply grows with nowhere to put it. Another market distortion that leaves a strange spatial footprint: With the activities that normally consume them on hold, commodities roam the earth aimlessly and people finally stay home.Good to see the Tech Access Partnership which "aims to supports developing countries to scale up local production of critical health technologies needed to combat COVID-19, including personal protective equipment, diagnostics and medical devices such as ventilators". It's a sharing platform for product information and technical guidance, and a place to form partnerships. On a related note, Nature explores why patent pooling is good for everyone.

And for Watson, the book is a means to name, document, and create a toolkit for a design movement. “Lo-TEK,” is built on “lesser known technologies, traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and indigenous cultural practices and mythologies,” as she writes in the book’s introduction. It explores the space where design and “radical indigenism” meet. Conceived of by Princeton professor and Cherokee Nation member Eva Marie Goutte, radical indigenism encourages us to look to indigenous philosophies to rebuild our knowledge base and generate new dialogues across genres. Watson is advocating a movement that merges these beliefs with design to yield sustainable and climate-resilient infrastructures.

I don't really know where to put this interview with Ingrid Burrington. It's got so many aspects - from the challenge of wanting to help in a crisis which limits how everyday skills can be useful, or the limits of 'doing no harm' in ventilator manufacture, to what form protest and resistance might take now, and the question of why, in 1969, could we put men on the moon but we can’t solve the problem of the ghetto, of poverty, of inner city crime? On warehouse workers at Amazon organising:

One of the extraordinary things to me about a lot of the worker organizing that is happening is their main demands are – and I’m not saying this is as a criticism – honestly not that radical....They’re not extraordinary requests. Given how high Amazon’s stock price is right now, they absolutely have the resources to respond to them. ... One of the things that’s extraordinary about it is the extent to which Amazon has refused.

One of the things that’s interesting in watching certain supply chains break down in this moment is looking at where there is actually flexibility and where there isn’t, where things are adaptable and where they aren’t. One of the things that is really central from a western, American perspective on the supply chain is that the inability to really, truly trace where things come from is a necessity by design. The premise of supply chain transparency is an idea that means well and is fundamentally in contradiction with everything a supply chain is optimized to do. They’re not designed to be transparent, they’re designed to be efficient. Part of that efficiency involves flexibility – No, I don’t know the name of the mushroom picker who got this particular mushroom in this particular forest. Fuck you, why do I have to know that?

How does information travel through the supply chain in such a peculiar way, so that I know to wait impatiently at my door at the exact moment my new iPhone will arrive—but no one really seems to know how it has gotten to me?

I set out to find the answer, and what I found surprised me. We consumers are not the only ones afflicted with this selective blindness. The corporations that make use of supply chains experience it too. And this partial sight, erected on a massive scale, is what makes global capitalism possible.

... But most companies are leery about revealing too much about their own logistics operations. It’s not only because they are afraid of exposing what dark secrets might lurk there. It’s also because a reliable, efficient supply chain can give a company an invaluable edge over its competitors.

...Bonanni suspects that companies’ inability to visualize their own supply chain is partly a function of SAP’s architecture itself. .... “If you look at SAP.... They never intended for supply chains to involve so many people, and to be interesting to so many parts of the company.” This software, however imperfect, is crucial because supply chains are phenomenally complex, even for low-tech goods.

...In reality, the nodes of most modern supply chains look much less impressive: small, workshop-like outfits run out of garages and outbuildings. The proliferation and decentralization of these improvisational workshops help explain both why it’s hard for companies to understand their own supply chains, and why the supply chains themselves are so resilient. If a fire or a labor strike disables one node in a supply network, another outfit can just as easily slot in, without the company that commissioned the goods ever becoming aware of it.

...On the one hand, this all seems very logical and straightforward: to manage complexity, we’ve learned to break objects and processes into interchangeable parts. But the consequences of this decision are wide-ranging and profound.

It helps explain, for one thing, why it’s so hard to “see” down the branches of a supply network. It also helps explain why transnational labor organizing has been so difficult: to fit market demands, workshops have learned to make themselves interchangeable.

We’ve chosen scale, and the conceptual apparatus to manage it, at the expense of finer-grained knowledge that could make a more just and equitable arrangement possible.When a company like Santa Monica Seafood pleads ignorance of the labor and environmental abuses that plague its supply chains, I find myself inclined to believe it. It’s entirely possible to have an astoundingly effective supply chain while also knowing very little about it. Not only is it possible: it may be the enabling condition of capitalism at a global scale.

....Tsing points out that Walmart demands perfect control over certain aspects of its supply chain, like price and delivery times, while at the same time refusing knowledge about other aspects, like labor practices and networks of subcontractors. Tsing wasn’t writing about data, but her point seems to apply just as well to the architecture of SAP’s supply-chain module: shaped as it is by business priorities, the software simply cannot absorb information about labor practices too far down the chain.

Erika Nesvold, who is the cofounder of the JustSpace Alliance, pointed out that people at this present moment who can think on the timescales of long futures and think about things like what we’re going to do when we have a fucking moon base – usually they have the resources to not be panicking right now. .... Part of the work of trying to restructure these really complex systems you’re talking about, that currently feel quite intractable and recalcitrant, is finding the wherewithal to think on that longer time horizon. Which feels very out of reach for a lot of people right now. Certainly it’s hard for me. I also think it’s understanding what are the tools you actually need. Engineering new systems, in this case – some of them are about technical problems, but most of them are political problems. The reason it’s apparently easier to go to the moon than to address poverty is because nobody in power has to give anything up to send someone to the moon.Jamais Cascio suggests a new framing for "the age of chaos" - moving from tools and ideas based on VUCA, to BANI.

VUCA is an acronym meaning Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous. The term has proven to be a useful sense-making framework for the world over recent decades. It underscores the difficulty in making good decisions in a paradigm of frequent, often jarring and confusing, changes in technology and culture.... The kinds of tools we’ve created to manage this level of change — futures thinking and scenarios, simulations and models, sensors and transparency — are mechanisms that allow us to think and work within a VUCA environment. These tools don’t tell us what will happen, but they enable us to understand the parameters of what could happen in a volatile (uncertain, etc.) world.

The concept of VUCA is clear, evocative, and increasingly obsolete. We have become so thoroughly surrounded by a world of VUCA that it seems less a way to distinguish important differences than simply a depiction of our default condition. Using “VUCA” to describe reality provides diminishing insight; declaring a situation or a system to be volatile or ambiguous tells us nothing new. To borrow a concept from chemistry, there has been a phase change in the nature of our social (and political, and cultural, and technological) reality — we’re no longer happily bubbling along, the boiling has begun.

... Scenarios, models, and transparency are useful handles on a VUCA world; what might be the tools that would let us understand chaos?As a way of getting at that question, consider BANI.

An intentional parallel to VUCA, BANI — Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, and Incomprehensible — is a framework to articulate the increasingly commonplace situations in which simple volatility or complexity are insufficient lenses through which to understand what’s taking place. Situations in which conditions aren’t simply unstable, they’re chaotic. In which outcomes aren’t simply hard to foresee, they’re completely unpredictable. Or, to use the particular language of these frameworks, situations where what happens isn’t simply ambiguous, it’s incomprehensible.

At least at a surface level, the components of the acronym might even hint at opportunities for response: brittleness could be met by resilience and slack; anxiety can be eased by empathy and mindfulness; nonlinearity would need context and flexibility; incomprehensibility asks for transparency and intuition. These may well be more reactions than solutions, but they suggest the possibility that responses can be found.

Why are we destroying morphine when it's in short supply? (Turns out this is a serious question for the Home Secretary.)