Weeknotes: problem solving, supply chains, government websites, manufacturing

I'm very excited about our upcoming maintenance event. Join us on Thursday: https://ti.to/festival-of-maintenance/social-care-2020

I hope we can build on the issues noted by Diane Coyle in this week's Talking Politics podcast about work, who does it and how it is paid for.

I actually originally got the idea, and you’ll probably remember this — it was in the Bay Area, it was in San Francisco, maybe like 2013, 2014. There was a story about a bunch of guys, Latino guys in the neighborhood, who every Sunday would get together and play five-five soccer on these five-by-five soccer field pitches in their neighborhood. And they’d do that, it was a tradition that had been going on for decades.Way too much tech is/has been made this way. It's such a big shift to get away from this mindset.

One Sunday they turned up there, and the field was completely overrun by white guys wearing Dropbox T-shirts. And they were like, “Well, this is our field.” And the guy turned to them and said, “No, but we booked it.” And he said, “Well, what do you mean? What do you mean you booked it?” And he pointed at the sign, a flyer that had been stuck up at some point in the previous week saying, “In the future if you want to use these playing fields you have to book them. You can do it by downloading this app to your smartphone.” And the guy that was talking to him goes, “I haven’t got a smartphone. This is my culture. This is what we do.” And the guys go well, I’m sorry, but that’s how it works now. You need a smartphone.”

Someone had come up with a solution — that’s so often the Silicon Valley way — to find a problem, then find a solution to it so that you can then make a product that fills that solution, and think that you’re being helpful without really considering the wider implications of what you’re doing. And what you’re actually doing is building this kind of extra-stratified society. You’re limiting access to people who only have smartphones. Arguably now, smartphone penetration is much higher than it was five years ago, but at the time it was a particularly stark and infuriating example, because the people who’ve done this, honestly to God, did not think they’d done anything wrong.

They really only see just that they were generating solutions for stuff. And that’s the stuff I write, this technology. As you well know from your own work and your own journalism, this is the stuff that’s most scary about it, is the idea that it’s providing universal solutions to things that have been decided are problems. It just ends up making it worse.

Brian Merchant: In the example that you just mentioned, it’s telling that the control is being handed over to the people who have the benefit of wielding, developing, or programming the technology in the first place — owning the technology.

Tim Maughan: The owning is the key point there because most people in this space have been sold book after book — hundreds of self-help books and courses and incubators and stuff that says, “Hey, look, you want to succeed in this industry? You need to find a problem that you can solve.” You get to the point of almost creating a problem to be solved. In order to show off your technical skills and your ability as a problem-solver, you need to find a problem. And even when that problem may not even exist, or it’s a different kind of problem, it isn’t a problem that needs a technological solution. It’s a problem that needs a political solution. It’s a problem that needs a community solution. It’s a problem that’s solved by fixing capitalism, not fixing technology. So many of our problems are byproducts of other systems. So that’s not what is of interest to people. People are interested in becoming an entrepreneur, in becoming a successful CEO, a successful founder.

Before Infinite Detail came out, I was at a workshop incubator thing in Brooklyn. And there was a couple of kids there — this is before Infinite Detail — and they said, “Oh, yeah, we’re making a smart trash can.” And I had started working on the recycling bit in Intimate Detail. I had written that chapter at the time, and my heart just fell. I said, “Right, so what is that? How does it work?” And they were like, “Well, it’s got a screen on the side. And when you put a can in, it thanks you for putting it in.” And I said, “Well, what’s the point? Why?” And they said, “Well, because it would encourage kids to recycle more. It’d be like little video games they can play.” And I’m thinking, “Okay, is it really that hard to get kids to recycle? I don’t feel like it is, but, anyway, whatever.”

I said, “What’s your business model?” He said, “Well, hopefully, we’ll get cities invested in it.” And I said, “Yeah, but…” And I knew exactly what his answer was going to be, and I kept pushing him on it. He said, “Well, yeah, eventually we do want to monetize the data it collects. Yeah, eventually we could be monitoring who’s walking past from the IDs on the phone or the footfall.” And that’s it. People are not even interested in fixing these problems. They’re interested in finding “solutions.” They’re finding other trajectories, other vectors to get data collection, that’s it because they literally have all been told data is new oil, and they fully fucking bought into this.

They don’t even know what the data is for. They’re not even interested in collecting data for specific reasons. They’ve just been told the data will have some value in the future, to grab and own and horde as much of it as you possibly fucking can.

There's a section later on in the article about Maersk container shipping, which is worth reading - partly for the way in which the container ship crew are utterly isolated from their role in the wider shipping network, and partly as (yet another) a reminder of how dependent on connected systems everything is.

Rachel Carey writes about the future of Zinc, the venture builder, and how they plan to work with social science. "Zinc brings together the brightest minds to build and scale a brand new way to solve the most important societal problems faced by the developed world." I like Zinc and supported their second cohort in a small way. I'm really pleased to see the social science aspect here, but I wonder how much of the above investment/tech culture will limit the ways in which it all gets applied. The Valley big tech firms hire a lot of social scientists, as Rachel notes, but I would be more cynical about the effects of this.

Martin Kleppmann notes:

The thread is interesting too, with quite varied responses...

Matt Stoller writes about fancy Rothy's shoes:

Such a high quality brand offers an enticing target for Chinese counterfeiters, who have found the perfect criminal accomplice: Facebook. Chinese counterfeiters are buying ads offering Rothy’s shoes for a low price, and directing people to fake websites. People then buy the shoes, which are counterfeit, and customers then complain to Rothy’s. Facebook does take fake ads down, but it is reactive, not proactive about doing so.The same issues apply to many brands, and to Google advertising too. As ever, it's interesting to see the other side of things to one's normal experience, in this case, what it's like to be a retailer:

... A few weeks ago, Rothy’s, like a lot of companies, pulled its ads from Facebook in solidarity with Black Lives Matter over Mark Zuckerberg’s policies around hate speech. Many companies did so, which had an interesting effect on ad prices. Facebook ad prices are done on an auction model, which means that high ad demand pushes prices up, and low ad demand pushes them down. With a boycott going on from advertisers, ad prices on that particular day were likely lower than usual. With no Rothy ads on Facebook and Instagram, and low ad prices, Chinese counterfeiters took advantage, and Facebook and Instagram were full of ads for fake Rothy’s.

... The law lets Facebook make a lot of money enabling counterfeiting. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act immunizes Facebook from any consequences for the content of ads bought on their platform; they can’t be sued for facilitating fraud and counterfeiting, so they don’t have any incentive to do anything about it.

... This dynamic involved something an early 20th century economist named Thorstein Veblen called “Absentee Ownership,” which is when the locus of control and the locus of responsibility are different. Facebook isn’t legally responsible for the consequences of what goes up on its network, but it still has control over what goes up on its network. Meanwhile, Rothy’s has responsibility for its brand, but no control over how Facebook sells advertising by counterfeiters exploiting its brand.

A few weeks ago, I got an email from a shoe retailer who told me about something odd happening with Amazon. He told me that his Amazon sales, which had been generally a high turnover reasonable business, were suddenly down 40%. He uses Amazon’s warehousing and logistics business, which is called Fulfillment by Amazon, which meant Amazon took care of making sure that his inventory got to customers.Despite investigations, described in the piece, they didn't get to the bottom of this issue, other than that the secret algorithms are frisky and Amazon doesn't help merchants much if at all.

Only, now that there were fewer sales, inventory began piling up, and he started getting warnings from Amazon that his metrics were below their standards and he was in jeopardy of losing storage capacity for the upcoming holiday season. This kind of million dollar penalty happens often among merchants who sell on Amazon, often randomly and for no discernible reason.

Increases or decreases in sales are a regular topic on the Amazon Seller Forums for merchants who have to sell through its Marketplace. Sometimes Amazon changes its algorithms or features for business reasons. But often stuff just breaks, and no one bothers to fix it. It’s hard to conceptualize this if you’ve never sold through Amazon, because as a consumer, the experience is generally good. But if Amazon has market power over you, the experience is one of hostile neglect.

Light relief.

Amazing: film crew video https://twitter.com/leesteffen/status/1289646377530785792

Footlights, 1997, on YouTube. I realise with some bafflement that these were (are!) my contemporaries. And that we did dress like that, apparently.

Bruce Schneier shares a summary of the Atlantic Council report on the history of software supply chain attacks - threats come from code signing, hijacked updates, poisoning open source, app store attacks (including developer tools).

Dave Birch highlights other security issues -

Jeni Tennison's 2012 piece (mentioned by Paul) is also relevant though. As it seems like institutions are losing authority and capability, perhaps the homogenous, character-free way in which all the big government departments are represented online is a loss we might regret?

In the meantime, ten years ago John Sheridan's work got our legislation online for the first time:

Dave Birch highlights other security issues -

A generation on from the famous “on the Internet nobody knows you’re a dog” cartoon that became a staple of management consultants’ presentations ever after, the situation is now far worse. Never mind no-one knowing whether you’re a dog, no-one knows whether you’re a toaster. Or a toaster pretending to be a dog. Or agents of a foreign power pretending to be a toaster presenting to be a dog that is intent on bringing down our online economy. If the Internet of Things (IoT) is going to be a platform for embedded financial services, then it will needs a serious security makeover.Following last week's note about the National Food Strategy website, Paul Clarke on the history of government websites, and the days of Directgov followed by the great unifying of gov.uk:

... Sooner or later a cyberspace Covid 3.0 will come along and then we are really in trouble. There’s no possibility of social distancing online because we’ve gone beserk connecting things up but we’ve overlooked how to disconnect them.

... Suppose it turns out that my smart toilet (these do exist by the way – I have photographic evidence) has been shipped from Korea with an old version of software that the hackers can easily exploit. Now my toilet is going to need patching and then upgrading. But supposing the facilities to patch and upgrade my toilet do exist (“do not flush – upgrade in progress – download complete in 22 minutes”), how will the manufacturers persuade me to do this? What if the manufacturers have gone out of business? What if the upgrade is itself a trick designed to subvert my toilet for the amusement or profit of Eastern European hackers?

Leaving it up to consumers will not work. We cannot trust the populace to configure their smart device firewalls any more than we can we trust pop stars to configure their iCloud, so selling toasters that can be hacked (even if it is by the CIA) ought become as unthinkable as selling cars without seatbelts. The noted security expert Bruce Schneier (one of the key thinkers in this space) has rather eloquently likened IoT’s market failure (which is that I don’t care that my toaster is insecure and is bringing down your bank, and neither does the manufacturer – it’s cheap and it works) to a kind of post-industrial pollution.

... As the Business Software Alliance’s recently-published principles for “Building a Secure and Trustworthy IoT” say, security policies should “incentivise” security through the IoT life cycle. That means a different mindset and its a mindset that sees the need for an infrastructure.

For bigger players in the Great Game of Government Departments, losing your website wasn’t necessarily the end of your independence as an operator, but you can see how it might feel a lot like it at times. Taking down the shop front was a Big Deal, all right.And usable sites which were accessible and navigable are a good thing.

So, lots of arguments, lots of strategising, lots of fudge, and plenty of healthy debate and opinions – I appreciated this counterpoint by Jeni Tennison – but with the heft of the Lane Fox report and a boot up the arse from the indefatigable Francis Maude in the Cabinet Office, they got there.

Sites converged to a single gov.uk domain, a place for everything (well, bar a few exceptions) and everything in its place. More than just convergence of branding and operation though – really tangible improvements like standardising the approach to content and service standards, and making sure that important stuff like accessibility was clearly and consistently supported. Perhaps it didn’t have to be all about cutting down variety and flexibility! Perhaps it was about a more structured and supported environment to let everyone be more effective at what they needed to do.

Jeni Tennison's 2012 piece (mentioned by Paul) is also relevant though. As it seems like institutions are losing authority and capability, perhaps the homogenous, character-free way in which all the big government departments are represented online is a loss we might regret?

So it is with these eyes that I look at the new Inside Government pages on the gov.uk site and am frankly horrified. Because we’re not just talking about a BBC programmes here, but about powerful institutions, many of them decades if not centuries old, that lie at the very heart of government and how our nation is run. And each of them is relegated to a subfolder of a subfolder of a subfolder, their unique histories and approaches and goals expressed through three pictures on a carousel.Back to Paul:

It feels like some kind of Orwellian nightmare: the relentless focus on user needs leading to a future of identikit pages, with no individuality, no character, no clue that behind these pages – which, remember, under the Single Government Domain policy becomes the single authoritative view, the site that represents the department on the web – is a living and breathing institution that manages hugely important parts of our lives.

... Last September, William Hague gave a speech in which he described the hollowing out of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) by the previous government, a process that scrapped its language school, closed embassies and destroyed its library. He said:

Strong institutions are necessary in civil society, to encourage participation and keep in check an overmighty State; they are necessary to our judiciary and Parliament so that the law is upheld and the making of it respected; but they are also necessary within the State, a point tragically overlooked by those Prime Ministers who have created and abolished departments on a fancy or a whim, destroying as they did so the pride and continuity of thousands of public servants while rendering government incomprehensible to the average citizen. The whole country should know what the Foreign and Commonwealth Office is and what it does, and all those interested in foreign policy at home or abroad should see it as a centre of excellence with which they aspire to be associated.

For most UK citizens, the only point of access to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office is its website: they will not visit King Charles Street, nor any of the UK’s embassies. The department’s web presence is the only way that it makes itself, and its unique role, comprehensible to the average citizen, the only method of letting the whole country know what the FCO is and what it does. And they have content that is completely unique to them: a database of Treaties, a hugely rich set of information on travel and living abroad and a wealth of historical information about the Foreign Office.

Because this morning I saw the delightful story of the collapse of the government’s bike repair voucher website. A government website? Surely that’s all looked after by gov.uk, user-tested, performance-assured, etc. etc. Ah. No.It feels like there should be a middleground here, where you can tell from a URL what authority a source of information has, and important state sites are accessible and usable, and yet big institutions - the FCO, say - have at least some brand identity on them. Perhaps I am too much of an idealist.

fixyourbikevoucherscheme.est.org.uk – yep. You read that right. We just slid back 11 years to the hand-rolled campaign URL! But it’s government, yes? What’s this EST bit anyway? Ah. The Energy Saving Trust. A part of government, surely? Er, no. It’s the Energy Saving Trust Limited – an independent, for-profit company, delivering stuff for government. Complicated, this mixed-sector provision stuff, it really is. But there were pictures of the bike-loving Johnson spaffed all over the launch blurb! Surely that means it’s government? Or claiming to be?

And that’s one of the big, big problems here. If you start tinkering with things that might be government, or are on the margins of, or deliver on-behalf-of-or-in-partnership-with government, then you get into sticky territory of trust and legitimacy. One of the concerns of the pre-convergence government web estate meshugas was that people wouldn’t get an accurate picture of what was ‘official government’ and what wasn’t.

... I spotted the launch of the government’s National Food Strategy. At nationalfoodstrategy.org – ah, yes, .org. So that’s…government, or not government? It’s the independent report, commissioned by Michael Gove when at Defra, but though that may smell very governmenty to the untrained nose, it isn’t. Or at least it is when the minister needs to be seen to be doing something about food strategy, but it isn’t until it’s been received from the estimable Henry Dimbleby and team, considered, and the government response provided. That would definitely then be ‘government’ and sit happily within gov.uk. Probably. Your guess is as good as mine.

In the meantime, ten years ago John Sheridan's work got our legislation online for the first time:

|

| https://twitter.com/johnlsheridan/status/1288436194922176513 |

Toby Shorin's "come for the network, pay for the tool" is about paid communities and content, and where they overlap. I think there's something interesting in the idea of smaller communities and clearly paying for tools to enable you to community better makes sense. And the conflicts between vested interests in the idea of a community (from Facebook to brand marketers to VCs) is helpfully noted. Toby's list of "businesses and communities could benefit from paid social networks" includes "Communities that govern things" but it's very focussed on crypto - co-ops already do this, so do other sociocracy/holocracy groups, and open source is another interesting example perhaps.

Organizations which try to bolt on community or social networks to their existing business model without building the capacity to understand and engage the people who make it up are likely to fail.

One of Web 2.0’s most crucial lessons is that extractive business models cannot be masked by marketing for very long. This is doubly true when the community itself is part of what people are paying for. Users will quickly turn on network operators if they sense hypocrisy or are given no voice in the development of the service. I am least optimistic about the prospects of paid social networks run by large corporations, brands, and IP holders.

... The inevitable failures, however, should not discredit the entire project of bespoke social networks designed around specific community needs. Prospective entrepreneurs, operators, content creators, and designers are the “social engineers” of these spaces, and here is found the transformative potential of the model. Here, design, development, and content creation are no longer merely tools for generating revenue; they are also tools of community organizing. Here, design and engineering take on the valence of care, and the emotional involvement of being a contributor, moderator, and member. Where does “design” end and “moderation” begin? Because the mainstream social networks have been designed by a tiny number of people, we have been prevented from experimenting and creating new knowledge about what sustainable community management online looks like. Start erasing the line between operators, customers, and community members disappears, and squint; you begin make out the shape of a group of people who can build for themselves and determine their own path of development.

One of my frustrations with the growing popularity of paid newsletters is that it becomes costly to span a range of different things in cash terms as well as time terms. If you have one or two niche interests, you can pay and get lovely relevant content. If you want to dip into a wider range, it gets expensive very quickly.

An interesting read on coalition operation in Lessons from Public Spaces:

Now that PublicSpaces, an alliance of twenty (semi-) public parties in media, festivals, heritage and healthcare, has celebrated its second anniversary, it is worthwhile to document our experiences and share what has been the best working method for the coalition so far.

PublicSpaces is a coalition of values, built on a shared concern about the state of the internet. This concern is not only abstract and 'far away', but also applies to the position of the participating parties proper. They all ask questions like: how can we use the internet in a way that is consistent with the values of our organisation and with public expectations? What is our own responsibility in this? What should we change in our own organisation and operation? And what tools do we have at our disposal to do this? These shared concerns and dilemmas form the basis of the collaboration.

Sharing values alone is not enough to create a successful coalition. You can agree on what you think is important, but if you subsequently disagree on how to achieve your goals, you have not made any progress. A certain shared view on the form of collaboration and realistic expectations of what the outcome may be are at least as important for success.

I've been enjoying my subscription to Byline Times. Here's a recent piece about PPE contracts... The weird procurement is only part of it:

|

| https://twitter.com/JolyonMaugham/status/1289447716955725827 |

It's rather depressing, but worth reading the whole thread. Then consider donating to the Good Law Project.

Steve Evans spoke about "manufacturing sustainability: back to the future" at an Institute for Manufacturing seminar, revisiting the 2013 Future of Manufacturing report. The 2013 report forecast various shocks and disruptions, although a pandemic didn't make the final summary cut (food, water, energy and politics were thought disruptive enough themselves!). Steve writes:

The report was based on a two-year consultation and engagement with experts across industry, government and academia. We took a long term view on what the manufacturing sector would look like out to 2050.One of the four key future characteristics of manufacturing identified in the report was that the industrial system would be more sustainable - and the report outlined wider changes in three broad phases.

The first phase up to 2025 focused on building efficiency and resilience. Seven years on from the publication of this report, and I’ve been considering how far we’ve moved along this first stage.

Here's the 3 phases:

|

| Manufacturing future phases from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/back-future-revisiting-manufacturing-report-7-years-steve-evans/ |

I liked Steve's description of himself as an "angry optimist" and might adopt that myself.

Evidently in the original report compilation, the third phase stuff about structures was all too political and people didn't get it - it made them uncomfortable. Steve noted that many companies are still in the first wave of change (and some are not even there), although things have definitely moved on to the second phase in many ways. (There's still an increasingly mistaken belief that manufacturing means jobs for averagely skilled young people, which has not been the case for a while. But can we use that misunderstanding to gain support for realistic changes?)

To cope with disruption - whether the coronavirus or other shocks - we need to tackle several things. Growth is one - Steve noted this was the gnarliest, and that as a politician, if you targetted growth you might actually limit it, but if you could target wellbeing, you might get growth. However, in industry, growth is all; as a CEO, if you double your profit on half your turnover, you will still lose your job, and so the push for scale (over profit or wellbeing) remains, and strains everything.

Onshoring for political reasons is as problematic as ever, but the benefits of making things locally, near customers, are sound. The importance of place is starting to be recognised much more than in 2013 - "place has meaning" now.

The final two aspects of manufacturing post-disruption are trust and resilience. Resilience is obvious of course; but the aspect of trust Steve focussed on was, alarmingly, whether we could continue to trust the law as a means to do business. He noted as an example the clothing contracts from January which were reneged on as the pandemic hit. I suppose the PPE procurement stuff above also falls into this category. Hmm.

The Q&A touched a little on what might be making Steve optimistic, as this had not hugely come out in his talk; I think there was some enthusiasm that it's now possible to say industrial strategy in Whitehall, although the implementation is not there yet. There's some nice innovation turning up in small companies (although there are still too many big companies, which tend to be "big but not strong"). He ended with a call to be efficient, which struck me for a

moment as slightly odd, as with a tech lens this seems problematic, but I

can see how with a manufacturing lens it's rather different.

I was left optimistic by the inclusion of the idea of a manufacturing commons in the third phase - the idea of manufacturing as a public good, perhaps with some degree of public ownership. (Steve cautioned against a focus on privatisation vs nationalisation, as being a very 1930s take on things.)

I've been enjoying the Twitter account which logs all the newly registered political parties in the UK. Volume is low, interest is high. Bot thanks to Jonty Wareing.

John Bull summarises how to design governance and notes that the pandemic communications from the government are not managing this [thread].

Tom Forth looks at how England's centralisation has played out in pandemic response. Perhaps centralisation has lead to more deaths, but a counterpoint might be that centralisation helps in treatment development.

Tom Forth looks at how England's centralisation has played out in pandemic response. Perhaps centralisation has lead to more deaths, but a counterpoint might be that centralisation helps in treatment development.

Building on the Build Back Better statement, and the Green New Deal for the UK, there's now a campaign underway with local organising to secure support from organisations, community groups and businesses for a combination of appropriate industry support, job creation through decarbonising, public health, key worker and care worker conditions, etc. Might be worth signing up. The informational webinar I thought I'd signed up for turned out to be a community organiser training call, and was excellent. There's no hub in Cambridge / Cambridgeshire, yet...

As Sam Weiss Evans wonders further down the thread, what evidence would convince you these were, or were not, part of a scheme of ecological warfare?

|

| https://twitter.com/SAWEvans/status/1288064275588800512 |

How much water does the UK use? Martin Appleby writes:

The average person should drink at least 2-2.5 litres of water a day. But drinking water is a tiny fraction of water used in the UK. At home, the average UK person uses 142 litres of water per day and a house of 4 uses around 349 litres per day. And during the COVID-19 lockdown this value increased in some parts of the UK by 25%, to approximately 175 litres of water per day per person.

142 litres is 9.5 times that used by someone who lives in urban Ethiopia, where it is estimated their average daily water use is about 15-35 litres per day (WHO recommend at least 20 litres per day for basic hygiene needs and 50 litres to be adequate).

... The hidden water cost is your total water use based on all the things you do, all the products you buy and use and anything else that could possibly use water (including electricity generation!).

Taking hidden water costs into account it’s estimated a person in the UK uses 3000 litres of water a day.

... The Government estimates that an extra 4 billion litres of water will be needed per day by 2050. You may notice this is only slightly higher than the loss through leakages, unfortunately there will always be leaks, so while this can be minimised it’s not the only solution.

Increased water demands are compounded by the fact that water companies are going to start extracting less water (1 billion litres per day) from natural supplies due to decreased rainfall. This will likely have been estimated using 143 litres per person per day estimate as opposed to the ‘hidden’ cost of 3000 – 5000 litres per day. It is not clear if this hidden cost is used by industries and agriculture when estimating water use.

So yes we need more water but fixing leaks will only do so much. Leaks cost a lot of money to fix and I doubt that the amount lost can be reduced completely. I also don’t know if this extra 4 billion takes into account future leaks, or leak fixing, because it might. In which case we may need even more water.

|

| from https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-how-discourses-of-delay-are-used-to-slow-climate-action |

If you like that, you might enjoy the new BBC podcast How they made us doubt everything.

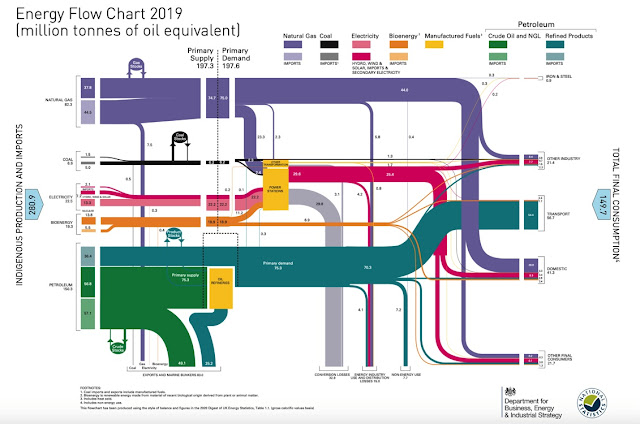

Thanks to various people on Twitter, BEIS's energy 'flow chart' (Sankey diagram) for the UK in 2019:

|

| https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/energy-flow-chart-2019 |

|

| https://twitter.com/frabcus/status/1288377573299359745 |

Time to get rid of patio heaters -

|

| https://twitter.com/alicebell/status/1288430424625221632 |