Weeknotes: maintenance, politics, housing, open science, misc

|

| https://twitter.com/tforcworc/status/1293953002185908226 |

The Festival of Maintenance event on social care with The Maintainers is now up on YouTube.

Festival colleague Naomi Turner writes about how hard it is to talk about maintenance:

We want to show the often surprising contexts which require maintenance, who maintains, or indeed where maintainers work.We need new imaginings to show us how things could be.

These could be aspects of maintenance with which we are familiar — the losing battle against potholes, bridge repair or the guerilla gardening movement in the wake of austerity policies in the UK. It might mean re-assessing the permanence of our immediate environment (for example, thinking about concrete not as solid but as a decaying, pseudo-organic material), and instead shifting to thinking about what it means to care for it in the medium or long term.

However, the more we innovate, build, create or procure in any area, the more we need to maintain.

... we’re also interested in the maintenance needed to make the internet work in the day-to-day. Ben Ward’s talk provided an insight into the battle of maintaining a system of Internet of Things sensors — a tangled mess of navigating expiring domain registrations, whilst protecting the sensors themselves against the wind, rain and moss. Our interest also extends to open-source software and the programmers who have a dual role in building and maintaining it — at the same time exploring the care of digital collections and archives at the British Library, or the community management without which Wikipedia would simply not exist.

... Examining maintenance as a collaborative activity might be a way to explore how maintainers from different disciplines might learn from each other, particularly when this kind of work is not always apparent or celebrated. Collaborative endeavours are rarely completely egalitarian — there is always delegation, negotiation and management of resources or other capital — that outsiders rarely see.

... Much has been written about how we don’t have the right words or metaphors for the internet yet. This absence inhibits what we build — for how can we create what we can’t yet imagine?

... With trepidation, I suggest that this is because maintenance falls outside of our current value creation system. This gets political fairly quickly, because understanding and accounting for maintenance practices may undermine who or what we currently think to be important. We know, of course, that the majority of unpaid household labour is carried out by women. If we think of life as predominantly a maintenance activity, it undermines the idea of a linear narrative of progress, the actors this empowers and the language we use to express it.

For me personally, maintenance is something of a gateway drug to thinking about power relations, new forms of cooperation and re-appraising how we privilege innovators (a tiny, tiny number of people) over maintainers (the rest of us). Like many, I find the hero-worship of these figures caustic, a damaging and simplistic narrative which conveniently edits out the labour of others.... It’s a myth so pervasive in our society that it proves hard to counter.

... At a deeper level, it’s about recognising the courageousness of caring for others — even indirectly through maintenance of systems or objects — particularly when this goes unnoticed.

A recent Zebras Unite webinar, celebrating the movement organiser's conversion to a co-op, included some inspiring messages. The coming "global depression" presents new opportunities to buy out failing capitalistic businesses, for instance. Jason Wiener discussed how problematic the deep connection between traditional startups and their founders is - the equity

stake, the investment focus, the key person insurance, the golden

handcuffs - the patriarchal and "utterly vain" nature of this structure -

and how co-ops demand untraining so leaders and investors can comprehend and operate in something different.

Is the upside enough to outweigh the additional governance load?

Well, the governance load is there for any organisation. I like the idea

that sharing the governance out means you avoid the potential toxicity

or risk around individuals. Most ventures - especially those taking a

systemic perspective or pursuing a mission - have a complex stakeholder

landscape to think about in their decision-making anyway. The co-op

structure makes that clearer, and perhaps more streamlined.

It was also interesting to hear a (US) panel talk about how co-operativism is an indiginous community concept.

Dina Gerdeman writes about how businesses which focus on community can survive crises:

In lessons for today’s businesses deeply hit by pandemic and seismic culture shifts, it’s important to recognize that many of the Japanese companies in the Tohoku region [devastated in the 2011 quake] continue to operate today, despite facing serious financial setbacks from the disaster. How did these businesses manage not only to survive, but thrive?

One reason, says Harvard Business School professor Hirotaka Takeuchi, was their dedication to responding to the needs of employees and the community first, all with the moral purpose of serving the common good. Less important for these companies, he says, was pursuing layoffs and other cost-cutting measures in the face of a crippled economy.

“Many Japanese companies are not that popular with Wall Street types because they are not as focused on gaining superior profitability and maximizing shareholder value,” he says. “They talk consistently instead about creating lasting changes in society.”

"Wise leaders bring different people together and spur them to action.”

Their reward for thinking beyond profits? These businesses tend to live a long time. In fact, on a global map, Japan stands out for corporate longevity; 40 percent of companies that have remained in existence more than 300 years are located in the country, according to Takeuchi’s research.

The article describes a variety of cases where leadership took action to support communities directly. HT to Beatrice Pembroke for sharing this.

Metrics drive so much, and I've been following a coops.tech thread about how to measure performance in co-ops, where the traditional business metrics aren't appropriate.

One option is developing something based on the balanced score card for co-op performance, beyond simply financial measures:

The social balance sheet systematically, objectively and periodically evaluates six major characteristics of any company or entity that wants to be socially responsible: economic functioning and profit policy; the gender perspective; equity and internal democracy; environmental sustainability; social commitment and cooperation; and the quality of the work.

Last week's 'moodlight' from Camplight co-op is also a potential measuring tool.

A beautiful talk from Jonathan Zong exploring typography, biometrics, individuality, and writing in the age of data (transcript). via Nathan Matias.

Why don't we have night trains under the Channel? Nicole Kobie looks into this for WIRED. HT Sam Smith.

How benevolent sexism holds women back (Guardian cartoon by Emma).

Tim Hayward [thread] describing many of the reasons I don't listen to many podcasts.

|

| https://twitter.com/timhayward/status/1293429448881115137 |

Tim Davies on data pledges and how they might work:

The ITU, under their “Global Initiative on AI and Data Commons” have launched a process to create a ‘Data Pledge’, designed as a mechanism to facilitate increased data sharing in order to support “response to humanity’s greatest challenges” and to ”help support and make available data as a common global resource.”.

... a tool to ‘collectively make data available when it matters’, with early scoping work discussing the idea of conditional pledges linked to ‘trigger events’, such that an organisation might promise to make information available specifically in a disaster context, such as the current COVID-19 Pandemic.

... [a Data Pledge might focus on] ... addressing those collective action problems either where:

A single firm doesn’t want to share certain data because doing so, when no-one else is, might have competitive impacts: but if a certain share of the market are sharing this data, it no longer has competitive significance, and instead it’s public good value can be realised.

The value of certain data is only realised as a result of network effects, when multiple firms are sharing similar and standardised data – but the effort of standardising and sharing data is non-negligible. In these cases, a firm might want to know that there is going to be a Social Return on Investment before putting resources into sharing the data.

... Pledging can also be approached as a means of solving individual motivational problems: helping firms to overcome inertia that means they are not sharing data which could have social value. Here, a pledge is more about making a statement of intent, which garners positive attention, and which commits the firm to a course of action that should eventually result in shared data.

Both forms of pledging can function as useful signalling – highlighting data that might be available in future, and priming potential ecosystems of intermediaries and users.

Tim also shares some concrete ideas as to how this might work for private sector pledges, in the absence of a meaningful data commons.

My professional institution has finally decided to go open access, a move I'm pleased to see after many years of feeling that publishing was not a viable business model these days. Thanks IET. I'll pay my (steep) membership fees slightly less grudgingly now.

I enjoyed this preprint on the history of the Global Open Science Hardware movement. Partly this is because it enriched my understanding of a space I've been adjacent to, and partly to see how Julieta Cecilia Arancio approached the study. Highlights mine -

Open science hardware (OSH) is a term frequently used to refer to artifacts, but also to a practice, a discipline and a collective of people worldwide pushing for open access to the design of tools to produce scientific knowledge. The Global Open Science Hardware (GOSH) movement gathers actors from academia, education, the private sector and civil society advocating for OSH to be ubiquitous by 2025. This paper examines the GOSH movement’s emergence and main features through the lens of transitions theory and the grassroots innovation movements framework. GOSH is here described embedded in the context of the wider open hardware movement and analyzed in terms of framings that inform it, spaces opened up for action and strategies developed to open them. It is expected that this approach provides insights on niche development in the particular case of transitions towards more plural and democratic sociotechnical systems.

... The hacker movement, which informs most open and collaborative, peer-to-peer communities (Benkler, 2006), is commonly associated with an ethos based on liberal values such as freedom of information and expression, right to privacy, meritocracy and the power of individuals (Coleman, 2004; Levy, 1984). However the articulation of these concepts takes different shapes through interaction with other backgrounds, creating a set of related but different expressions around property, work and creativity (Coleman and Golub, 2008). One of this expressions, trans-hacktivism, presents intersecting points with previously described framings: it combines concepts from hacker culture with intersectional feminism and queer theory, critical pedagogy, technology decolonization and autonomism.

... Lessons learned also point out that more radical niches have to “prove” more important benefits in order to influence the regime, but that this is not a static process: how radical the niche is perceived to be and how important its benefits are, change with time and with the emergence of tensions in the regime. Which tensions in the regime can be framed as opportunities for OSH? Is it the context of a global COVID-19 pandemic, where the patented model of production leaves the world’s hospitals and workers short of vital tools, a tension strong enough to open an opportunity?

Thinking again of a scenario with OSH as default, the designs of certified personal protective equipment (respirators, goggles, garments) and medical/laboratory equipment (ventilators, PCRs for tests, tools for vaccine research) are openly released – some suppliers are already doing it – and available online. Using these public specifications, industries that produce other similar goods can reorient their processes more easily to fulfill some of the demand.

Fablabs and makerspaces can quickly grab PPE designs and start producing for their communities and local hospitals. Differently from now, makers don’t have to reverse-engineer but can adapt already performant and safe designs, saving precious time in coordination and production, avoiding undesirable side-effects such as governments trying to homologate DIY designs. OSH as a default also means more laboratories can process samples for testing, access more equipment for working towards vaccines, and produce them faster.

... The course OSH takes towards influencing the current way of doing science depends on many factors within the sociotechnical system: activists’ strategies, context tensions, emergence of policy supporting OSH and new business models based on openness, the ability of institutions to adapt, cultural shifts in academic practice, public perception. The proposal of imagining possible near futures for OSH taking into account historic lessons is intended to promote reflection on strategies to foster change at these different levels, taking into account the new political configurations that will necessarily emerge in these new scenarios.

I particularly appreciated the discussion of imagined futures and how these might inform strategies for change.

Things have certainly quietened down in the world of local PPE manufacturing and procurement. We had a reflective session to write up a timeline and key learnings and reflections, whilst they were still things we could recall. It was eye-opening how early our group was aware of stuff - key challenges around coordination were apparent in mid-March - and some of us were already moving to scale manufacture via injection moulding even then. We had quite detailed breakdowns of face shield production volumes across the UK and demand estimates by early April. At the same time some connections appeared very late - the link between my local hospital and the local resilience forum which had access to stockpiled PPE wasn't made for a very long time.

The thought of Brexit and import chaos coinciding with a potential infection wave in winter is a worrying one - whether we are importing PPE, or materials. We felt, overall, that the UK's production capacity is much increased, and the supply networks of makers and health and care users of PPE are much stronger now. There are factories ready to start manufacturing - but they will still need material, and no one has a mind to stockpile this. Hmm.

Virus testing with logistics from the private sector is not going well.

Fintech is often held up as a hotbed of innovation but perhaps that isn't quite working out. Dave Birch writes:

Well, there’s a story that I tell at seminars now and then about a guy who was retiring from a bank after spending almost his entire working life there...Dave goes on to note that AC did indeed make a measurable productivity difference in the US.

The guy in question had risen to a fairly senior position, so he got a fancy retirement party as I believe is the custom in such institutions. When he stepped up on stage to accept his retirement gift, the chairman of the bank conducted a short interview with him to review his lifetime of service.

He asked the retiree “you’ve been here for such a long time and you’ve seen so many changes, so much new technology in your time here, tell us which new technology made the biggest difference to your job?”

The guy thought for a few seconds and then said “air conditioning”.

... So while there are individual fintechs that have been incredibly successful (look at Paypal, the granddaddy of fin techs that is going gangbusters and just has its first five billion dollar quarter), fintech has yet to fulfil its promise of making the financial sector radically more efficient, more innovative and more useful to more people.In other news, Matt Webb has been looking at making it easier for people to learn about and use RSS.

I can illustrate this point quite simply. While I was writing the piece, I happened to be out shopping and I went to get a coffee. I wanted a latte, my wife wanted a flat white. While I was walking toward the coffee shop, I used their app to order the drink. The app asked which shop I wanted to pick up the drinks from, defaulting using location services to the one that was about 50 yards away from me. Everything went smoothly until it came to payment. The app asked me for the CVV of my selected payment card, which I did not know so I had to open my password manager to find it. After I entered the CVV, I then saw a message about authentication. What a member of the general public would have made of this I’m not sure, but I knew that they message related to the Second Payment Services Directive (PSD2) requirement for Strong Customer Authentication (SCA) that was demanding a One Time Password (OTP) which was going to sent via the wholly insecure Short Message Service (SMS). Shortly afterwards, a text arrived with a number in it and I had to type the number in to the app. The internet, the mobile phone and the app had completely reinvented the retail experience whereas the payment experience was authentication chromewash on top of a three digit band-aid on top of a card-not-present hack on top of a 16-digit identifier on a card product that was launched in a time before the IBM 360 was even thought of.

The FT piece describing this surprising information is here.

The UK built environment isn't ready for new extremes of weather, warn experts in the Guardian:

The government’s statutory advisers, the Committee on Climate Change, called for new regulations to protect people from rising temperatures. “The recent heatwave shows how ill-suited the current UK building stock is to hot weather, and the risk that overheating poses to us all,” said Kathryn Brown, head of adaptation at the committee. “Yet there is still no legal requirement to ensure homes, hospitals, schools or care homes are designed for the current or future climate. This urgently needs to change and be part of a wider programme of retrofitting and designing buildings within a green economic recovery package.”We need to demand zero carbon homes, says Rachel Coxcoon, in a thread where she sets out what's needed here - changes in the planning system and building regulations, because these are the only places where housing developers are forced to do things - and enforcement, and local placemaking.

... Geoff French, former president of the Institution of Civil Engineers, pointed to the Stonehaven derailment as an example of what can happen when deluges strike. “Cuttings, slopes and so on need to be checked more frequently,” he said. “The challenge is to identify the most critical infrastructure and deal with that. You need to reduce the knock-on impact, when one piece of infrastructure fails.”

Much of the UK’s infrastructure dates from the Victorian age, when the climate was less prone to such high temperatures and the risk of flash flooding. Roger Kemp, professorial fellow at Lancaster University and fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering, said building new houses, streets and transport networks to those old specifications and templates no longer made sense. “If you look at other countries, their drains are deep and wide but we are still building as the Victorians did.”

Since the privatisation of utilities in the 1980s and 1990s, the emphasis has been on keeping down costs to billpayers, rather than investing in better infrastructure. “That was a mistake,” said Kemp. “The cultural shift has not happened: people haven’t woken up to the need to invest yet.”

Centralised government was another problem, he added. “This stuff is not very sexy, and governments like big prestige projects. There is a place for unspectacular improvements to be carried out by local authorities.”

... While the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, announced £2bn for refurbishing homes to be more energy efficient, the question of protecting them against excessive heat was not mentioned. The wrong type of insulation can reduce ventilation and turn homes into heat traps in summer.

|

| https://twitter.com/RachelCoxcoon/status/1293202647374274561 |

Surprising:

|

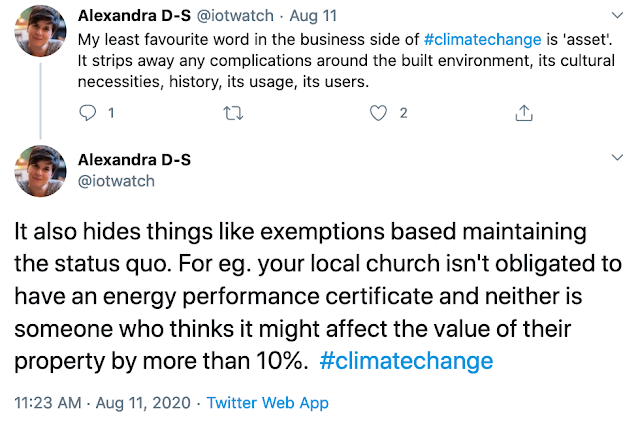

| https://twitter.com/iotwatch/status/1293131003796623360 |

Also from Alexandra's twitter, a grim office future:

|

| from https://twitter.com/iotwatch/status/1294218729434357760 |

If you have a place to live, you can soon rent John Lewis furniture, in a deal not entirely unlike hire purchase.

If you are a university lecturer, you might need help setting up your home office. This is an all too accurate reproduction of many academic offices I have seen.

Making Your Zoom Look More Professorial from Andrew Ishak on Vimeo.

|

https://twitter.com/mryderqc/status/1293829481082355712 |

Via Adrian McEwen, if everything is politics then everything is power, writes Thomas Friedman in the New York Times:

But a society, and certainly a democracy, eventually dies when everything becomes politics. Governance gets strangled by it. Indeed, it was reportedly the failure of the corrupt Lebanese courts to act as guardians of the common good and order the removal of the explosives from the port — as the port authorities had requested years ago — that paved the way for the explosion.

... To put it differently, when everything is politics, it means that everything is just about power. There is no center, there are only sides; there’s no truth, there are only versions; there are no facts, there’s only a contest of wills.

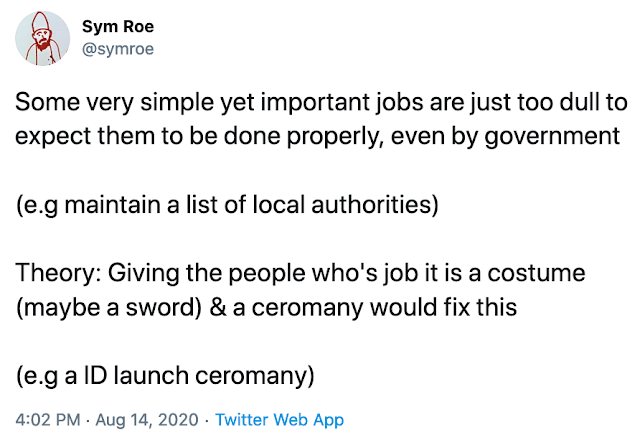

Maybe Sym has the answer to the problem that some work appears dull:

|

| https://twitter.com/symroe/status/1294288403312398341 |

Make Votes Matter is organising a day of action to demand proportional representation in the UK. HT Mike Butcher, who notes "Only two countries in Europe still use First Past the Post: the UK and Belarus!" which seems a quite astonishing fact.

First, disrupt the political power of polluters (via Ian Brown):

|

| https://twitter.com/BeterOpDeFiets/status/1293144030453338114 |

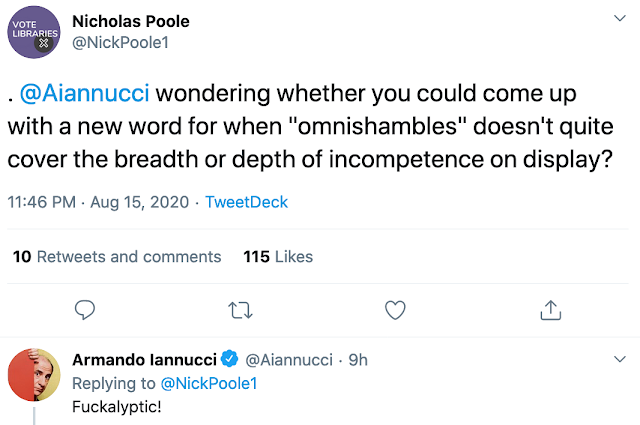

It's been a week of exam algorithm news and debate. I noted Tom Forth's thread on how the exam grading system was developed - including a big consultation, and info on other research into grading. But exams are a broken system anyway, says Dan Davies in the Guardian (a point of view echoed by actual examiners...)

But even if, impossibly, all the problems had been solved, the Ofqual report on its own methodology gives the game away with respect to a much more serious issue. If there had been a perfect solution to the problem of a pandemic-hit examination process, so that every candidate was given exactly the grade that they would have got in an exam, how fair would this be? Turn to page 81 to see the answer and weep. In any subject other than maths, physics, chemistry, biology or psychology, there’s no better than a 70% chance that two markers of the same paper would agree on the grade to be assigned. Anecdotally, by the way, “two markers” in this context might mean “the same marker, at two different times”. For large numbers of pupils over the past several decades, it’s quite possible that grading differences at least as large as those produced by the Ofqual algorithm could have been introduced simply because your paper was in the pile that got marked before, rather than after, the marker had a pleasant lunch.

|

| https://twitter.com/NickPoole1/status/1294767500828319746 |

Oh hai

|

| https://twitter.com/genmon/status/1292927583567392768 |

Also

|

| https://twitter.com/Symbo1ics/status/1292808078698610688 |

Thanks to Ross Jones for that one.

Are we all feeling our age this week? Tom Coates [thread]:

|

| https://twitter.com/tomcoates/status/1291523937998798848 |

Maybe the exciting stuff is elsewhere, calling itself different things, not inviting xennials to the party. Or maybe times just changed.