Weeknotes: the home, tech reporting, technocratic government, dependencies

Kelly Pendergrast's superb essay on the home body (HT Deb Chachra, whose work runs along similar lines):

In the real world of the cyborg collective and its composite parts, the horrors of the house are entirely non-metaphoric. Turn a tap in some parts of Flint, Michigan, and poisoned water still flows out, years after the city’s water crisis became a national disgrace. Plug in a power cord anywhere, and the electricity that flows your way might be fed by atrocities carried out in your name at the other end of the tubes: black lung, denuded environments, death. Unlike the privatized horrors of storybook hauntings, the spirits that animate my house exist on the same timeline, as part of the same networked system as I do (hello sanitation engineer, hello bird flying splat into the wind turbine, hello coal miner), at the other end of the tubes, feeding my housebody or failing it.

... The risk, as I see it, is that infrastructural tourism results in a remystification of infrastructure, either by documenting and reifying its seemingly-inhuman monumentality, or fetishizing complexity for its own sake, disregarding the power structures that undergird it, and the suffering they cause.

Wallowing in the logistical sublime can lead to what Matthew Gandy describes as “epistemological myopia that privileges issues of quantification and scale over the everyday practices that actually enable these networks to function.” But I get it. And I’ve felt it: the uncanny mystique of larger-than-life steel and concrete power plants, or the gut-drop of standing on the edge of a dam spillway, imagining yourself slipping over and sluicing into the deep canyon of water below. In part, these fantasies of the sublime are a symptom of our alienation from infrastructural systems and the powers that animate them. If it’s not clear whose interests infrastructure serves, and how our own lives and housebodies are enmeshed in the macro systems, the only thing left to do is spectacularize, fetishize, or destroy.

... Unfortunately (or fortunately), we can’t take care of ourselves alone. Within the city, especially, our ability to live comfortably and maintain our bodies and communities depends on the branching networks of pipes and tubes and the labor that feeds into them. We’re enmeshed in the infrastructures of the collective cyborg even when it’s clearly failing us, undermined by rot and capital. I want the intimate care I feel in my household nest to be extended across the entire system, but instead I walk through the neighborhood and spot only the ruptures. People locked out of obscene housing markets, clothing stores peddling jeans for which rivers were dyed blue and made deadly, and public toilets that always seem to be locked. I want to see it torn down, but I also want to see it repaired, so it can repair us.

... Still, I want more for us than to spend every precious moment scrambling to arrange childcare or make sure our friends don’t get evicted. Collective care without the collective assemblage of infrastructure is near impossible, so we need to figure out how to maintain the systems that still function, and how to fix the ones that are broken or working against us.

In some cases, pieces of the existing collective cyborg will need to be dismantled. The pipelines that cut across Native land and spill oil onto the prairie: those can go. The highways that slice through neighborhoods, benefiting those on one side of the divide while immiserating those on the other: those can go too, ripped up for barricades and projectiles, “the use of the city against the city, in the name of the city.” Other parts can stay but must be redistributed, brought into collective ownership so the waters and warmth and phone lines are shared equitably and wrested away from the profit motive. Infrastructure is a massive investment, and much of that investment has already been made. To maintain it, to take care of the far-reaching tendrils of the homes that sustain every day, is the best way to respect what we’ve already created, already ruined.

... I try to remember that I’m not alone in the house. Firing up the gas burner, I make note of the denuded gas fields of Alberta that feed the gigantic stove my landlord provided, big enough to cook for a small commune or at least for a medium-sized Food Not Bombs operation. Flick on a lightswitch and I wince briefly, picturing the dry August hills crackling beneath the PG&E pylons, ready for an errant spark. I turn on the shower and prompt a ripple all the way up to the Hetch Hetchy reservoir (ancestral home of the Miwok and Paiute people, evicted from their land by the U.S. government). Zoom and FaceTime bring colleagues and friends alike into the domestic space, where they observe the messy living room from their perches inside the laptop screen. Fine. This is part one of the work; to develop an extended proprioception that includes an awareness of the animate energies of the housebody, but also extends out through wires, pipes, and cables and towards all the other things and people the system touches, cares for, harms, and fails. Because the infrastructures of the home mean that we’re inexorably intermingled, codependent, and beholden, even as we might feel more disconnected than ever. To survive, we need to build the strategies and solidarities that allow us to maintain the infrastructural systems that serve us — an act of self-care beyond the boundaries of the self.

Steve Evans followed up his webinar (my notes) with a short video of the excess Q&A. I'm not sure he really understood my question, about his description of new work needed around social stuff and where the skills will come from for that - or perhaps he is just very optimistic about the learning abilities of manufacturing engineers even in spaces so unlike their training and experience. He proposes that we stop taxing jobs (income tax) and instead go all out on taxing energy and material and water use, as this will push for sustainability very effectively. On local vs global manufacturing, he noted that when you bring a container of goods made in China to the UK, the first 100miles of truck transport from Felixstowe has a higher carbon impact than the entire boat journey from China. We perhaps focus on the wrong problems sometimes. There's a nature paper out now which suggests the Sustainable Development Goals won't be met because of the pandemic. Steve suggests the model of 'let's have a big economy, generate wealth and use some of the wealth to sort out SDGs' was always broken anyway.

Via Adrian McEwen, Andy Matuschak on production instead of consumption:

|

| https://twitter.com/andy_matuschak/status/1294696060380569601 |

The whole thread, including thoughts on Patreon, is good.

On the other hand, there's this from Drew Austin:

|

| https://twitter.com/kneelingbus/status/1295547265797558273 |

Obituary of Bernard Stiegler by Stuart Jeffries. HT Alexandra Deschamps-Sonsino.

His sense was that we have entrusted our rationality to computational technologies that stop us thinking authentically. One of his most astute interpreters, Leonid Bilmes, wrote that Stiegler saw that “the catastrophe of the digital age is that the global economy, powered by computational ‘reason’ and driven by profit, is foreclosing the horizon of independent reflection for the majority of our species, in so far as we remain unaware that our thinking is so often being constricted by lines of code intended to anticipate, and actively shape, consciousness itself.”

Technology, which could have been a liberation, was leading us to extinction. “For a plane to fly, you have to follow a number of laws of gravity and physics,” Stiegler said. “We know how to do it, planes fly very well. But in doing so, we only take into account the short term: if we chose to certify the planes only on condition that they do not eat up all the resources for the next thousand years, they would not be allowed to fly.”

... In The Neganthropocene (2018) he argued that individuals and society at large are increasingly shaped by algorithms and automated systems, driven by economic rather than human interests. A Facebook feed, for instance, was algorithmically devised to keep you inside its digital walls so you can be exploited for profit.

To disrupt this exploitation of humans and the despoliation of the planet during the Anthropocene age, he established several interdisciplinary projects, including a group of politicised researchers called Les Liens qui Libèrent (the links that iberate). That group’s book Bifurqer (bifurcation or parting ways), which was published under Stiegler’s direction in the spring, called for an end to “bullshit jobs” and to “de-automate automatisms” so that humans could live in sync with their biosphere.

“Today, bullshit jobs are no longer the preserve of blue-collar workers,” he and the other authors wrote. “All employees, who sell their time spent carrying out useless, meaningless tasks, have them too.” Stiegler was inspired by the physicist Erwin Schrödinger, who coined the term negentropy, the trait of all life that resists the drift towards disorder.

Nick Romeo writes about Marietje Schaake, starting with an event where she spoke alongside Eric Schmidt. (highlights mine)

Where Schmidt emphasized the future, Schaake stressed the present; where Schmidt dwelled on the private and the technological, Schaake foregrounded the public and the political. “I’m going to talk about governance,” she began, before beginning a forceful critique of Big Tech’s extreme aversion to regulation, its unchecked collection of personal data, and its steady erosion of democracy. She brought up the ethics statements that committees and conferences like the one she was addressing tend to generate. “It’s a very popular topic,” she said, referring to A.I. ethics. “It’s also hard to be against ethics. . . . How do we make sure it’s meaningful and enforceable, and not just window dressing?”

Schaake proceeded to answer her own question with a long wish list. “A.I. development should promote fairness and justice, protect the rights and interests of stakeholders, and promote equality of opportunity,” she said. “A.I. should promote green development and meet the requirements of environmental friendliness and resource conservation. A.I. systems should continuously improve transparency, explainability, reliability, and controllability, and gradually achieve auditability, supervisability, traceability, and trustworthiness.” She paused before revealing that she had been reading from “Principles of A.I. Government and Responsible A.I.,” an ethics statement produced by China’s national committee of A.I. experts the previous June.

Ha ha.

Groans and laughter rose from the crowd as they realized what this meant. If China could issue such a lofty inventory of ideals while simultaneously surveilling and suppressing its citizens, then Silicon Valley could as well. The Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence was arguably dedicated to producing just these sorts of grandly empty assurances. If it’s hard to be against ethics, it’s just as hard to be against “human-centered” A.I.; there are no institutes for “inhuman” or “machine-centered” artificial intelligence. Schaake’s speech was a pointed message: talk is cheap.Randomly I came across Brighter.ai - "Deep Natural Anonymization" - image and video anonymization software to protect identities.

... “Silicon Valley is not usually seen as a policy hub, but, of course, it is one,” she said. “I saw that there was more Silicon Valley in Europe than Europe in Silicon Valley, and I felt maybe this should change.”

In conversation and lectures, Schaake often describes herself as an alien, as if she were an anthropologist from a distant world studying the local rites of Silicon Valley. Last fall, not long after she’d settled in, she noticed one particularly strange custom: at parties and campus lectures, she would be introduced to people and told their net worth. “It would be, like, ‘Oh, this is John. He’s worth x millions of dollars. He started this company,’ ” she said. “Money is presented as a qualification of success, which seems to be measured in dollars.” Sometimes people would meet her and launch directly into pitching her their companies. “I think people figure, if you’re connected with Stanford, you must have some interest in venture capital and startups. They don’t bother to find out who you are before starting the sales pitch.”

A fascinating idea from Nathan Schneider [thread]

|

| https://twitter.com/ntnsndr/status/1296198469519015945 |

Via Sander van der Linden, obviously:

|

| https://twitter.com/j_lindenberger/status/1296480122493706240 |

A fascinating paper by Sam Harnett - Words Matter: How Tech Media Helped Write Gig Companies into Existence. Highlights mine:

Manjoo was part of a collective media swoon over companies like Uber and TaskRabbit. It lasted for years and helped pave the way for a handful of companies that represent a tiny fraction of the economy to have an outsized impact on law, mainstream corporate practices, and the way we think about work. The content generated by swooning pundits and journalists made it seem like these companies were ushering in not only an inevitable future, but a desirable one. They helped convince the public and regulators that these businesses were different from existing corporations – that they were startups with innovative technology platforms designed to disrupt established firms by efficiently connecting consumers to independent, empowered gig workers. This was not only false, it was the exact rhetorical cover these companies needed to succeed.

Journalists and pundits both normalized and at times generated this rhetoric and framing. It was then repeated by politicians, amplified by academics, and finally enshrined in laws that legalized the business models of these app-based service-delivery companies. It would be years before some media organizations began taking a more nuanced and critical approach to the companies in the “sharing economy” that they helped write into existence. By then, it was too late. Venture capital had been gained. Consumers were habituated. Lobbyists were at work. New laws were on the books and IPOs were on the way. The force that fueled this media swoon was a relatively new and journalistically problematic trend in media: “tech” reporting.

... The conventions of the tech beat primed reporters to pump up these apps as disruptive and innovative advancements for consumers. This framing distorted the real, common business model of these companies, which was to use the banner of “tech” to avoid regulations, drive down labor costs, and undercut competition. The innovation-disruption lens dehistoricized these app-based service-delivery companies, clouding how they fit into decades-long trends like the erosion of worker earnings or the increase in compulsive consumption. This not only benefited app-based service-delivery companies, but was factually inaccurate.

... When I started covering companies like Uber, I found myself increasingly encountering these problematic terms. These included Silicon Valley-speak like “pivot,” “friction,” “innovate,” “disrupt,” “platform,” and “startup,” but also big, baggy words like “freedom” and “efficiency.” Companies like Uber and Lyft got their own section on my list with terms like “transportation network company,” “gig,” “rideshare,” “sharing economy,” and “collaborative consumption.” I fought to cut these terms, but I was sometimes overruled or had to settle for scare quotes because editors thought these words were essential and benign. Eventually, the editor I was working with came to understand that a word like “startup” was editorializing because it was endowed with positive associations (new, fresh, not your typical corporation!) yet provided no concrete definition (how old can a startup be? how many employees can it have? how much revenue?).The presence of these words subtly change the way readers and listeners think about the companies in question. Being deemed a “tech” company is a massive brand boost. “Tech” corporations have traditionally had high consumer favorability ratings and have not been scrutinized like firms in other industries.

... If tech was the key to the business, then you would think a company like Lyft or Uber would have been worried about Flywheel. The San Francisco taxi industry developed the Flywheel app to exactly mimic Uber and Lyft, but these companies weren’t scared at all. That’s because the reason they were able to offer rides more conveniently and cheaper than taxi companies had nothing to do with technology. They were able to put as many cars on the road as they wanted and pay drivers as little as possible because they were using the guise of technological innovation to avoid transportation regulations and labor laws.

It is true that once a company like Uber achieves scale, it requires computer engineers to adapt or create new tools that potentially push the boundaries of digital technology. The true tech stories at these companies are about managing server traffic and crunching data quickly. These are the tasks most of the employees with PhDs in computer science are working on at the company. But this kind of tech story doesn’t make a catchy “tech” journalism headline. When Uber posted a detailed article on its blog about the work involved in managing over 100 petabytes of data, the post made few media ripples, which isn’t surprising. It's difficult to find any article about the actual computer science and technological advances happening at companies branded as “tech.” That’s because the modern tech media ecosystem has evolved to have a particular set of conventions.

... Wired was not just a magazine about hardware, software, and video games, but a publication that looked at the whole world through a digital lens. The digital revolution was happening, and Wired was going to be the first to tell you about it. Establishing this editorial viewpoint was one of the three major ways Wired laid the groundwork for today’s modern tech ecosystem. The second was injecting traditional magazine formats with the techno-utopian, digital-positive tone and the opinionated, first-person, review style of earlier tech publications. The third and biggest impact was simply proving the existence of a broader general audience for tech news.

... There are many characteristics of the modern tech media ecosystem that result in misleading journalism, especially in the case of app-based service-delivery companies. First is the format problem: that wide-eyed, first-person review-style inherited from older tech publications. ... A second major problem is that modern tech reporting lost almost all interest in covering actual technology. ... The third major problem is the imperative to break the story. This is always a pressure in journalism, but it’s ramped up even more for tech reporters, whose reputation is staked on being the first to know about the latest new thing. This encourages reporters to create and repeat jargon which furthers the case that what they’re writing about is truly new.

Adrian Hon notes how Amazon is not just collecting data, but preventing anyone else from finding or using it. [thread]

|

| https://twitter.com/adrianhon/status/1295045795390148609 |

A taxonomy of cargo bikes via the Prepared.

Rachel Coldicutt writes about one of the most annoying things about this year:

Dominic Cummings’ techno-enthusiasm is infectious — and, this year, it’s been spreading all over government.

There doesn’t appear to be a written plan — at least not in the public domain — but there are certainly recurring themes. This is a dream of a low-friction, innovation paradise in which numbers tell the truth while bureaucrats (and ethicists) get out of the way. It is less a vision for society, more an obsession with process and power.

... The emergence of a patchwork of UK innovation initiatives over the last few months is notable. Rather than fiddling with increments of investment, there is a commitment to large-scale, world-leading innovation and enthusiasm for the potential of data.

But there is also a culture of opacity and bluster, a repeated lack of effectiveness, and a tendency to do secret deals with preferred suppliers. Taken together with the lack of a public strategy, this has led to a lot of speculation, a fair few conspiracy theories, and a great deal of concern about the social impact of collecting, keeping, and centralising data.

But it seems very possible that there is actually no big plan — conspiratorial or otherwise. In going through speeches and policy documents, I have found no vision for society —save the occasional murmur of “Levelling Up” — and plenty of evidence of a fixation with the mechanics of government.

This is a technocractic revolution, not a political one, driven by a desire to obliterate bureaucracy, centralise power, and increase improvisation.

And this obsession with process has led to a complete disregard for outcomes.

... “It’s important we draw the distinction between the decisions we make and the outcomes those decisions generate” shows a complete disregard for consequences. Barclay seems to be dismissing whole disciplines here — including risk management, project management and plain old commonsense. And Gove, in fact, says something similar:

“We need, as a Government, to create the space for the experimental and to acknowledge we won’t always achieve perfection on Day One… some projects will misfire, some will seem promising but fall at the final hurdle, but along the way we will end up with unexpected gains”

This would be fine if Gove and Barclay had teamed up to run a Young Enterprise Initiative after school on Wednesday afternoons, but it doesn’t quite work for governing a country in a national emergency. Some things should be safe bets; some things should just work; some things should be tried and tested, and there should be forms to fill out and budgets and roadmaps and committees and lawyers.

... The insistence on secrecy and lack of oversight has blighted both projects — as has the inability to define what good looks like for the public.

Success for grading this year’s A levels could have been defined at the start as “ensuring fair treatment for outliers”, and every subsequent decision mapped against that.

Success for track and trace might have focussed on effectiveness rather than process and exceptionalism; instead of pursuing a go-it-alone, centralised strategy that aimed to be “world-beating”, England could have aimed to “collaborate as broadly as possible to save lives”.

In both cases, the strategy was confused with the method of delivery.

Openness and transparency are also essential, not just for cultivating public trust, but because they make it possible to work with others and benefit from good advice.

For some reason this made me think of:

|

| https://twitter.com/quantian1/status/1296878195116048387 |

Africa's Voices has published their annual report for 2019. Their work is so impressive and significant, it's worth looking at the whole report.

Our truth is the power of citizen voice. In the five years of Africa’s Voices, it became apparent that evidence alone, as nicely packaged and presented as it may be, is not the means to the end of accountability. Returning to the fundamentals of citizen voice and demonstrating that there are novel and better ways to listen has been our most powerful tool in engaging decision makers, forcing them to see beyond the frameworks they normally operate in. Ultimately, to achieve action and accountability we must begin by changing the ways we listen.

... There’s been an undeniable revival of the discourse on accountability and participation within the aid space since Africa’s Voices was born. But there have also been legitimate doubts as to whether such ideas are truly valued rather than merely a nice-to-have and whether the political economy of aid can withstand and genuinely sustain such commitments. Introduced into the norm of technical expertise that diagnoses problems and proposes solutions, citizen voice is a disruptive force because, more often than not, it leads to conclusions that don’t fit in the silos and prevalent frameworks of the aid sector.

At the same time, it’s hard to believe that downwards accountability is genuine when aid agencies are inevitably first and foremost accountable upwards, towards donors and towards media scrutiny, reducing downwards accountability to yet another project activity. This is why, the space for accountability needs to enlarge, it needs to become more independent in order to achieve real change. This can only be done through more radical approaches and ultimately, less business-as-usual and more creativity.

... Africa’s Voices was different from the beginning. Innovation is part of our DNA. But while there is a lot of support for innovation at face value within the aid world, it’s difficult to be different in a space that thrives on labeling and categorising. AVF is not a research firm per se (though it has come out of research) and it’s not a frontline aid deliverer (though it helps frontline deliverers align their work with the opinions of the people they serve). It’s a charity, enabling change that is transformative, yet not the kind you could fundraise for in the streets of London or New York. It’s been a challenge to grow an organisation that doesn’t exactly fit in a box and it’s a reminder of the ways in which the wider structures within aid can sometimes hamper or hinder change.

From last week's Liminal call, pitfalls for facilitators from Johnnie Moore:

I think I've been all of these at times. It's good to have this reminder of what to watch out for :)

I've been motivated for some years by Cassie Robinson's approach to what is often called 'work life balance,' and her reflections this week on what this means as a leader in an organisation are interesting. And the highlights are mine again:

I’ve been reflecting on what it means to be a ‘leader’ who is being asked (by some people in my team) to ‘role model’ working in a way that is ‘good’ or ‘healthy.’ Those are not my words by the way. I’m fascinated by this — and you have to remember that I am someone who had never been on PAYE until the age of 39 so generally traditional work culture and practice is pretty foreign to me. There are so many fine lines to tread here. A lot of what we have normalised in work culture is to suit heteronormative lifestyles — those are defined and determined by having partners, children, families, ‘hobbies’ etc, and that brings with it all kinds of assumptions about where people find meaning and purpose, or like to spend their time. It’s also a hangover from industrialised work where people spent their days on factory lines — which I know many people still do but it isn’t what work looks like for everyone, anymore. There’s also something quite paternalistic (and problematic?) that I want to shy away from when you think that someone more senior in the hierarchy of an organisation needs to model something for those more ‘junior.’ Aren’t we all responsible adults? For many years now I’ve been someone that doesn’t have much distinction between my ‘work’ and my ‘life’ because I’ve been fortunate to do work that is intellectually stimulating, stretches me, connects me with amazing people and most importantly propels me from it’s roots in a social purpose that feels far bigger than me or any entity that I may be working with at any one time. Anyone that knows me also knows I have a life rich in connection — with friends, with family, with landscapes and other interests. When people call me a ‘workaholic’ I feel like their whole perspective on the world is coming through such a different lens. I do what the times require of me. Sometimes it is that simple. Sometimes I do get some rest or time away, often I work really long hours. I don’t think I show up in my role frazzled, sick or being ineffective. I hope I bring care, attentiveness and consideration with me. I’ve paid a lot of attention to how much of my time I give to the team or those I line manage (about 30% of my week) — so I kind of resent being asked to slow down, clip my wings, stifle myself — which are my words as that is how it can sometimes feel. Having said all of this, I know too that it really is something I need to work out how to do better — to tread that fine line. Key will be creating a team culture where people feel comfortable and able to work in the way that suits them — knowing there will be no judgment — and that the only expectation that comes with that is to have enough awareness of what the team needs too, and how the ways in which they choose to work has an impact on others.Slightly late to this rant by Heather Burns, about the gap in career understanding between academics, lawyers etc and digital/web people. It's a good example of how different fields aren't just about the subject, but all kinds of expectations and attitudes.

I’m seeing a lot of highly intelligent professionals who seem to think that improving online privacy is a matter of enhancing training and education that developers already have, or nudging them to pull their socks up where their compliance practices have slipped....

you can work full time on online privacy and still not actually understand it.

As I write in my upcoming book, the amount of developers and web practicioners who told me that my conference talks were the first training and education they had ever received on privacy, at all, anywhere, from anyone, ever, was terrifying. That is representative of the field as a global whole.

The overwhelming majority of web practicioners have no training, education, or guidance in online privacy.

Much responsible tech development considering security, reliability, people, etc, faces the same issues.

Via Sam Weiss Evans, the depressing reality of grant funding:

|

| https://www.smbc-comics.com/comic/funding |

Via Vicki Boykis, a CBC feature on an academic journal that focusses on predictable results.

Menclova is an associate professor at the University of Canterbury and the editor of a new journal called The Series of Unsurprising Results in Economics [SURE].Andrea Menclova says:

The mission is simple: only publish research with findings that are boring.

"I think science has a problem and it's a problem with publication bias.

We believe that a lot of the other journals are biased in the other direction — towards publishing attractive, catchy, strong, statistically significant results.

We kind of want to fill the void and publish results that are the opposite of that —unsurprising, weaker, statistically insignificant, not conclusive and so on."

|

| https://xkcd.com/2347/ |

I've been enjoying the webinars around the new Digital Infrastructure RFP. In the most recent, one point struck me: Caroline Sinders talked about on how the javascript world uses codes of conduct. There are many different events and communities within javascript alone, with codes, and they all derive in some way from the original Geek Feminism one. However, all these codes are different! They aren't learning from each other at all, it seems, there's no sharing or best practice, just local modifications, which seems a big wasted opportunity.

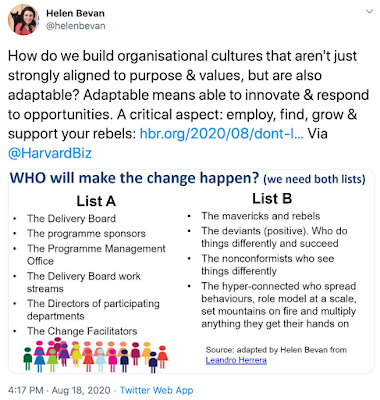

|

| https://twitter.com/helenbevan/status/1295741737290407945 |

Yet another not-open-source but trying-to-do-software-better licence:

What is the Anti-Capitalist Software License?

The Anti-Capitalist Software License (ACSL) is a software license towards a world beyond capitalism. This license exists to release software that empowers individuals, collectives, worker-owned cooperatives, and nonprofits, while denying usage to those that exploit labor for profit.

How is the Anti-Capitalist Software License different from other licenses?

Existing licenses, including free and open source licenses, generally consider qualities like source code availability, ease of use, commercialization, and attribution, none of which speak directly to the conditions under which the software is written. Instead, the ACSL considers the organization licensing the software, how they operate in the world, and how the people involved relate to one another.

The Anti-Capitalist Software License is not an open source software license. It does not allow unrestricted use by any group in any field of endeavor, an allowance that further entrenches established powers. It does not release your project to the creative commons or public domain, nor does it require derived source code to be made available. The availability of source code is less important than the organization of software labor.

Slow Ways, a project to make it easier to find walking routes between places

|

| https://twitter.com/SlowWaysUK/status/1294889426703855616 |