Weeknotes: Social imagining, distributed manufacturing, civil society

I started this week reading Cassie Robinson's write up of her recent talk, which was fascinating and nourishing and open (and also raising questions at the start about the nature of big keynote speeches). It covered quite a lot of ground, starting with Cassie's experiences in design:

Cassie goes on to talk about how we think about the future.

She ends with a lot of provocative questions and ideas. Can we take storytelling and narrative from an individual focus to the collective - the constellation of stars, or even the galaxy? How do we balance kindness and challenge?

Comakery is a platform to help you find people to work with on projects. I remain skeptical of many of these token projects, but this one is at least tackling an interesting problem space.

A new paper from Nesta (well, from last month) on data and trust. The "new framework for data governance" diagram helpfully sets out a little more structure for 'data trusts' and gets us to more accessible and clear language. This builds on lots of other work, such as Stefaan Verhulst's 'data stewards' (data collaboratives as noted here). I liked this bit of clarity:

A great thread from Jeni Tennison about how 111 could be supported with tech.

This is a nice change from the many poorly thought out hacker projects suddenly emerging at the moment, especially some of the "let's make a ventilator, how hard can it be" variety.

As Hannah Stewart astutely notes:

Hannah links to a 2017 post here from the thoughtful folks at Dark Matter Labs, on the need for new institutions and infrastructure for distributed manufacture. I wrote about related issues in 2017 too, looking at the needs of distributed manufacturing in the context of humanitarian relief and broken supply chains (this is my most recent paper). The same issues apply here, now - we need to remember the differences between a hacked up solution and the ideal item (made and tested rigorously against standards). The hacked up solution might be good enough in a crisis, but the users (medical staff, say) need to know how it might differ from what they are used to.

A good overview of how maintenance for electric vehicles is different to that for petrol ones, from Reilly Brennan.

A UK co-op for electric car charging in your local area is seeking investment.

From Sophie Sampson, a BBC blog about chatbots and creativity, and lots of interesting ideas about interactive storytelling (even though I didn't do very well at Catfish).

You should hire Tom Armitage. He makes things, this week including https://voipcards.tomarmitage.com/ for which the amusing advert is here.

Rachel Coldicutt writes about smart cities, and related topics.

Finding positive things - I couldn't justify the cost or carbon of travel to New York and so had assumed I'd have to miss this year's Open Hardware Summit. But when they shifted to an online event, I was happy to buy a ticket and had a great day of talks, chatter and community. Thanks everyone who made that happen, so smoothly, on a terribly tight timescale.

Trees as Infrastructure is a lovely long essay from Dark Matter Labs about ways we could better support urban trees. A lot of the model reminds me of CoFarming.

A reminder of some fine 1990s comedy on The Day Today, for Britain in crisis.

A terrific commercial.

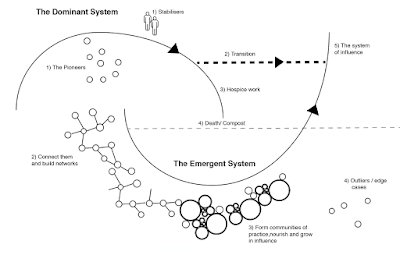

During this unconventional and varied set of experiences, I learnt too about the biases people have.There's a great middle section looking at the Berkana Institute model for change, with the multitude of roles across the dominant and emergent systems, all needed for things to move on. I've seen this diagram before but the descriptions of all the different roles (and recognition that they are all valuable) and how it all fits together in depth were very helpful here.

How much people want to put you in boxes.

How much people need a job title or an organisational association to assign value to you.

How much people are afraid of you for not conforming, or because they don’t understand you.

How much people can’t cope with just how much you do and how many different things you do.

|

| diagram from https://berkana.org/ |

Cassie goes on to talk about how we think about the future.

...talking about the future of civil society and was struck by how the room only seemed able to imagine civil society as being about delivering services.Cassie goes on to describe social dreaming - a new idea for me - and how we might use a patterning of hope to imagine positive futures.

Lauren Berlant says we are stuck in a ‘State of Impasse’ — a moment where existing social imaginaries and practices no longer produce the outcomes they once did, but no new imaginaries or practices have yet been created.

I believe there’s an absence of an organised social imagination.

A US-based academic, Kyung Hee Kim, who evaluated data from the main creativity test done there since the 1960s, concluding that imagination and IQ rose together until the mid-1990s, at which point they parted, imagination going into a ‘steady and persistent decline’.

And I’ve found that most people really struggle to articulate a plausible, desirable picture of society in the medium term or in one or two generations time. All of us find it really easy to describe the apocalypse.

... Given what’s happening all around us, I can understand why our imagination isn’t at its best! It’s still a concern though, because without that ability to imagine, without being able to perceive a future, we don’t have the pull to transition from the old to the new, or to keep creating and building.

It’s interesting to think about how much the technology world invests in its version of this — the smart city, the smart home, driverless cars, but the social sector, civil society, it doesn’t seem to do this. Is this because the institutions that cultivated our imaginations no longer exist? University’s aren’t able to do it anymore, political parties used to invest much more in foresight, and think tanks used to do this but are now primarily part of the news cycle meaning they have to feed current news agendas.

However there are two pretty predictable trends if we’re looking 50 years in to the future. Working hours are going down and life expectancy is probably going up....

However, this could mean millions of hours will be freed up. .... It could also become an extraordinary resource for social imagination and creativity, with a parallel economy growing that is much more centred on care, maintenance, art etc. The question is how do you actually organise for that, in new ways?

She ends with a lot of provocative questions and ideas. Can we take storytelling and narrative from an individual focus to the collective - the constellation of stars, or even the galaxy? How do we balance kindness and challenge?

Self care has been taken to its extremes and we’ve forgotten how important it is to keep your word, to stick with your commitments, to be consistent, to show up when you said you would, to do what you said you would do. That’s how trust and relationships deepen. That’s how we are really there for one another.

Which reminds me of this mention of the lesson of Voltaire - better to be honest than to be good.

Comakery is a platform to help you find people to work with on projects. I remain skeptical of many of these token projects, but this one is at least tackling an interesting problem space.

A new paper from Nesta (well, from last month) on data and trust. The "new framework for data governance" diagram helpfully sets out a little more structure for 'data trusts' and gets us to more accessible and clear language. This builds on lots of other work, such as Stefaan Verhulst's 'data stewards' (data collaboratives as noted here). I liked this bit of clarity:

An important challenge in any discussion of data is to use the right terms. Some widely used terms may impede rather than illuminate the choices. A key example is the use of a language of ownership and property. These terms seem intuitively clear and relevant, and lead some to want arrangements in which data is monetised—so if I agree to share personal data I should be paid for it.

But the language of ownership is not very meaningful upon closer inspection. In contrast to oil or other physical goods, data is everywhere, virtually infinite and non-rivalrous. It is more like an element than an object and just as factual information and abstract ideas can never be ‘owned’ by any single individual, neither can data—it exists conceptually separate from authorship. In a similar vein many have argued that data is really more like a public good than a private one...

The value of data tends to grow less through accumulation than through linking and analysis. Its value is determined not by the strength of boundaries around it but by the number of links it has. What matters is who is collecting the information, who is controlling it, and who is using it. The important analytical point becomes differentiating between ‘holding ownership of data’, and the ‘rights to access and control data’.

But even ‘rights over data’ can be ambiguous, both from a legal and ethical standpoint (e.g. what rights do I have over personal health data that might help the world stop an epidemic?). As we have attempted to show in the above framework, the answers will always depend on the specific context and uses.

|

| https://twitter.com/KateLeeCEO/status/1237827422361473027 |

A great thread from Jeni Tennison about how 111 could be supported with tech.

This is a nice change from the many poorly thought out hacker projects suddenly emerging at the moment, especially some of the "let's make a ventilator, how hard can it be" variety.

As Hannah Stewart astutely notes:

|

| https://twitter.com/Freerange_Inc/status/1239477107698413573 |

A good overview of how maintenance for electric vehicles is different to that for petrol ones, from Reilly Brennan.

A UK co-op for electric car charging in your local area is seeking investment.

From Sophie Sampson, a BBC blog about chatbots and creativity, and lots of interesting ideas about interactive storytelling (even though I didn't do very well at Catfish).

You should hire Tom Armitage. He makes things, this week including https://voipcards.tomarmitage.com/ for which the amusing advert is here.

Rachel Coldicutt writes about smart cities, and related topics.

What do I mean by “Just enough Internet”?Of course. I have the T shirt (actually a hoodie)

It’s a Goldilocks test: just enough to make services run more efficiently, not too much to deepen existing inequalities, not so much that it turns us all into algorithm-driven zombies. The idea is inspired by my search for a digital equivalent to Michael Pollan’s famous mandate: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

... as well as being a quest for moderation, Just enough Internet is also a rebellion against the notion that governments and corporate tech platforms need to defer corporate tech platforms to define “good”.

Don’t collect the data if you don’t need it. Don’t digitise it if it works better offline. Don’t force users to upgrade their technology to use your service. Don’t make your service look like a magic trick.

It’s a plea for common sense.

I can’t think of a single smart city meeting I’ve been to that has also involved people who run playgroups or food banks, or people from charities that support older people or young offenders; I can’t remember anyone who organises a carnival or a street party or a local football game, or faith leaders, or support workers from domestic violence charities. I’ve mostly heard from businessmen and people who think the Internet is really cool.The Collective Action Labs will be addressing this:

Civil society organisations have a mass of, often-neglected, expertise on how life is really lived and the kind of society people want to live in. As Lucy Bernholz says (similar to Catalyst’s mission), “Civil society must create or call for digital systems that reflect civil society’s values”, not just be expected to tidy up when tech goes wrong or take part in performative post-it noting.

I’ve been wondering what other kinds of intelligence the breadth of civil society organisations can and should bring to discussions about technology, and how to build confidence in, and support that.

The space between the market and the state is vulnerable in the technology landscape: it gets squeezed by big organisations, tight timescales and incomprehensible jargon. The Collective Action Labs offer a chance to nurture and invite other organisations in to help build digital civil society.

... culture, politics and people shape a smart city as much as the technology.And so to thoughts from Ed Mayo about co-ops and charities:

For instance, Gebeid Online is a decentralised social network for Amsterdam, owned and managed by the communities that use it, that is more a product of the place and the people than it is of its (fairly generic) software. Sidewalks Labs in Toronto is the gateway to the Googleverse; it is full of fancy technology, corporately owned and lacking transparent governance.

The Toronto project might appear to be “smarter”, but it definitely lacks “urban intelligence”. Gebeid Online, meanwhile, is made of urban intelligence. A liveable city is more than a technocratic vision of just-in-time bus distribution, targeted ads or on-demand rubbish collection. It’s a place for people, shaped by people

For the charity sector, co-ops are business clubs focused on private gain – values-based, open and entrepreneurial. That is seen as in contrast with a wider public purpose – indeed charity law tends to test public benefit negatively, through the absence of private benefit.

For the co-operative sector, philanthropy is about the public works of private people – generous with their time and money, prosperous, often establishment. That is seen as in contrast with the working class roots of the self-help movement – participatory and emerging out of need.

Each probably think the other is in some way the status quo – charities representing a more traditional, paternalistic approach to service delivery, co-operatives being part of markets that still leave people in need.

In reality, each has always aimed higher, at transforming society through values.

..... Charity is associated in the public mind with the call for new money. Yet there are billions of pounds of charitable assets that lie dead and dormant rather than being used to challenge and change society: beautiful paintings; wonderful halls in city centres; legacy foundations administered by banks and accountants. I am told that one penny in every pound traded on the stock exchange is on behalf of the charitable sector.

.... One of the great innovations in the co-op sector recent years, thanks in part to solicitors such as Anthony Collins, has been the development of a robust model of what we might call a ‘multi-stakeholder’ governance. If you are a worker co-operative, what about the customers? If you are customer-owned co-op, what about the workers? The multi-stakeholder model, still one member, one vote but within weighted constituencies, operates as a 360 degree co-operative.

In Wales, one of the leading social care charities, Cartrefi Cymru, has converted to a multi-stakeholder charitable co-op, because giving a voice to users, people with learning disabilities, carers and to staff can give them back their dignity. As Adrian Roper, Chief Executive of Cartrefi Cymru says, decrying the marketisation of care based on competition and a race to the bottom:

“if you feel that behaving like rats in a sack is a deeply inappropriate and resource-wasting way for social care providers to act, and you see no evidence that charitable status is any guard against rat-like behaviour, then co-operative principle 6 (co-operation amongst co-operatives) calls to your soul.”

In Italy, this model – multi-stakeholder social co-operatives providing care, health and employment services – has grown from 650 in 1985 to seven thousand today, with 244,000 staff and 35,000 volunteers.

....the community benefit society model has been a ‘game changer’ in that it is a model that encourages communities of people to come together to support charitable projects, through their time and fiscal investment, on a democratic one-member one vote basis. This uses traditional co-operative models of equity capital raising from members in a new setting, called ‘community shares’. Over the last decade, around 150,000 people have co-invested over £150 million in over 500 community businesses through this approach.

Equity like this is what most social ventures need – patient over time, asset-locked equity capital that can be crowd-funded from your supporters. It is not a pushing of expensive short-term debt, which is sadly what a fair amount of social investment passes for. As a member, you don’t see capital gains and your money is at risk, but you can be paid interest on your investment and you benefit as a member from the success of the society...

Finding positive things - I couldn't justify the cost or carbon of travel to New York and so had assumed I'd have to miss this year's Open Hardware Summit. But when they shifted to an online event, I was happy to buy a ticket and had a great day of talks, chatter and community. Thanks everyone who made that happen, so smoothly, on a terribly tight timescale.

Trees as Infrastructure is a lovely long essay from Dark Matter Labs about ways we could better support urban trees. A lot of the model reminds me of CoFarming.

A reminder of some fine 1990s comedy on The Day Today, for Britain in crisis.

A terrific commercial.