Weeknotes: commons, negative capability, events

I updated my website. I'm on the lookout for my next main job, and in the meantime available for short term consultancy projects.

(Many thanks to Ira Bolychevsky for some of the motivation to get that done, and Liminal people for ideas and feedback :)

It was fascinating to get a sense of the corporate response to climate risks (especially those of finance and insurers) at the Business Risk from Climate Change event last week. There's more business readiness to respond than might be apparent from the outside. Banks, for instance, are now seeing climate change as a financial/operational risk, not just a matter of reputational risk and CSR. I liked the idea of talking about "disruption days per year" as a different way of assessing climate risk than "once in a century floods."

On the opposite end of the spectrum, I met the Cambridge Carbon Map team who are working at a grassroots level to create a public map of carbon emissions in the city. They are part of Cambridgeshire Climate Emergency, which has a super collaborative, community power-building ethos.

Ignoring the specific technologies, this is an interesting exploration from Venkatesh Rao of text as a medium online (HT Patrick Tanguay).

I also wonder whether the podcast boom idea is focussed on a certain listener demographic. I seem to encounter quite a lot of people in, well, low-cognitive-demand work, who are not listening to podcasts. Cleaners, for instance, who are on the phone with friends and family.

I've been gradually moving newsletter subscriptions over from email (where they get in the way of things needing actions or replies) to RSS, using Kill the Newsletter. This means I can read them when I'm doing slower reading, or at least, reading rather than processing email, which is useful.

I'm interested to see whether Fraidycat could help me manage things to read/watch better (HT Sam Elliott). It aggregates feeds from multiple platforms and presents views of who has been active recently. I'm unclear how much of what I follow is oriented around people, rather than things. Pondering this reminded me of unreliable social networks, and also my longstanding wish for aggregators and services that don't fixate on what's popular, but what's a little less popular. (I'll see the popular news many times anyway, without it needing extra emphasis; but the link shared by only one person in my network is probably the weak signal that will help me understand trends better.)

Via Adrian McEwen, Doc Searls article about the commons and the internet seemed mostly interesting for the list of types of enclosure at the start. It's easy to fixate on one or two things - big tech platforms, personal data control, say - and to miss the other structural factors that have changed internet dynamics.

It seems to be the year to question open tech. Via Azeem Azhar, a thought-provoking paper by Balázs Bodó about whether the open knowledge commons is a "curse":

Via Andrew Sleigh on Twitter - the idea of negative capability.

The Festival of Maintenance will run on Saturday 10th October 2020, in Liverpool.

This was a week in which I attended an event where an organiser commented that the corporate attendance was low, as many were already being hit by reduced travel policies related to coronavirus.

What are the best ways to run an online event? Janet Gunter prompted me to wonder about this, as did my conversation with Cambridgeshire Climate Emergency. Zoom has quite a lot of in-built support for smaller events but there must be other options out there. (I still recall remotely attending the 2008 Sakai conference, with University of Michigan support for Second Life so we had a 'corridor track' as well as live video streams from the sessions. Second Life is less of a thing, now; it would seem sad if we've regressed in terms of remote event tech though!) I'll be collecting some ideas for this with ClimateAction.tech in the coming weeks.

A bit late, as it's been 2020 a while now - I finished reading the Well's State of the World and wrote up some notes. Some of the bits that stood out for me were Bruce Sterling's thoughts on the world at large; some the state of making.

"Boris" is the equivalent for setting goals of the "negotiated joining" method of hiring for uncertain situations (mentioned last week).

A nice readable paper from two thoughtful Cambridge institutions - the Institute for Manufacturing, and the Bennett Institute for Public Policy - about how we may be misunderstanding manufacturing levels in the UK because of the way industry is counted and classified.

It's hard to disprove some fears about technology surveillance. Via a convoluted Twitter thread, an academic study into whether Android phones are listening to their users.

Precious Plastic's recycling system has launched their v4 system, a big step forward with

It's fifty years since the first national women's liberation conference in Oxford; papers on childcare, women's employment, etc, still relevant today.

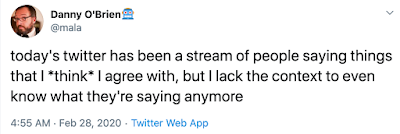

And finally Danny O'Brien with a lovely little thread that I very much relate to.

(Many thanks to Ira Bolychevsky for some of the motivation to get that done, and Liminal people for ideas and feedback :)

It was fascinating to get a sense of the corporate response to climate risks (especially those of finance and insurers) at the Business Risk from Climate Change event last week. There's more business readiness to respond than might be apparent from the outside. Banks, for instance, are now seeing climate change as a financial/operational risk, not just a matter of reputational risk and CSR. I liked the idea of talking about "disruption days per year" as a different way of assessing climate risk than "once in a century floods."

On the opposite end of the spectrum, I met the Cambridge Carbon Map team who are working at a grassroots level to create a public map of carbon emissions in the city. They are part of Cambridgeshire Climate Emergency, which has a super collaborative, community power-building ethos.

Ignoring the specific technologies, this is an interesting exploration from Venkatesh Rao of text as a medium online (HT Patrick Tanguay).

Email today is now less a communications medium than a communications compile target. It’s a clearinghouse technology. It’s where conversations-of-record go, where identity verification happens, where service alerts accumulate, and perhaps most importantly for publishers, where push-delivered longform content goes by default.I mostly agree with this, but it also hints at the challenge of email for many people. Service alerts do fill inboxes - I see this and it shocks me, because mine have been filtered away to a never-looked-at folder for so long. How do people stand getting email alerts about, say, Twitter mentions, when they already have a beep and a counter on their app icon and often a popup alert too?

The podcast boom (and to a lesser extent, the video boom on YouTube) currently exists almost entirely as an artifact of two social phenomena: commuting and low-cognitive-demand chores, both of which call for a low-information-density ambient background information flow.I can see this up to a point. I struggle with podcasts - in fairness I tend not to struggle long, because I give up. The signal to noise ratio is all too often too low; the hosts too full of themselves. Was I ruined by BBC Radio 4 being my "low-cognitive-demand chore" listening for so long?

I also wonder whether the podcast boom idea is focussed on a certain listener demographic. I seem to encounter quite a lot of people in, well, low-cognitive-demand work, who are not listening to podcasts. Cleaners, for instance, who are on the phone with friends and family.

I've been gradually moving newsletter subscriptions over from email (where they get in the way of things needing actions or replies) to RSS, using Kill the Newsletter. This means I can read them when I'm doing slower reading, or at least, reading rather than processing email, which is useful.

I'm interested to see whether Fraidycat could help me manage things to read/watch better (HT Sam Elliott). It aggregates feeds from multiple platforms and presents views of who has been active recently. I'm unclear how much of what I follow is oriented around people, rather than things. Pondering this reminded me of unreliable social networks, and also my longstanding wish for aggregators and services that don't fixate on what's popular, but what's a little less popular. (I'll see the popular news many times anyway, without it needing extra emphasis; but the link shared by only one person in my network is probably the weak signal that will help me understand trends better.)

Via Adrian McEwen, Doc Searls article about the commons and the internet seemed mostly interesting for the list of types of enclosure at the start. It's easy to fixate on one or two things - big tech platforms, personal data control, say - and to miss the other structural factors that have changed internet dynamics.

It seems to be the year to question open tech. Via Azeem Azhar, a thought-provoking paper by Balázs Bodó about whether the open knowledge commons is a "curse":

The knowledge commons, as we implemented it through the free and open source software licenses, and through those creative commons licenses that many of us worked on in different jurisdictions were a mistake, because they rest on the wrong assumptions, and are permeated by the wrong ideologies.

...

The open commons idea was also compatible with the nature of digital information. If digital information is infinitely copiable, if the core of the problem is that it is both hard and undesirable to limit the circulation of digital files, if there is no scarcity in the digital world, then the open commons logic works the best, as it also aims to remove artificial legal barriers from the circulation of creativity.

...

Commons based peer production was the ultimate prize, the practice of utopia... It was marketed by Benkler (Benkler 2006) and others as the third alternative, which can peacefully co-exist with the market and the bureaucratic control. The commons, and the peer production logic was so attractive, because we though we didn’t need to worry about the tragedy of commons, because the resource it produced, and the resource it relied on for its survival was inexhaustible, it was knowledge, it was imagination, and even if it was taken in bulk by others, that could not upset the commons itself.

And this proved to be the fundamental error we made. We though knowledge commons were inexhaustible, and therefore we would not need to think about their use. ...

But this double blindness of not thinking about its use, because the commons was open, and keeping the question of extrinsic motivations away, because they did not fit the ideal of peer production resulted in a huge blind spot: that of value. One of the key questions that we very consciously did not address was the question of value, of value extraction, and value redistribution. We failed to conceptualize the relationship between individuals, their motivations, the value of their labor with which they produced, and maintained the commons, the aggregate value of the shared resource pool, and the necessity of material resources to maintain that pool.

Via Andrew Sleigh on Twitter - the idea of negative capability.

Negative capability is such a tantalizing juxtaposition. Keats fanned the flames of intellectual curiosity for many philosophers/designers/org theorists [a group to which I’ll now add systems thinkers] when he described it as a state in which a person ‘is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason’. (Keats, 1970: 43.) I think it was the “without irritable reaching” that has us most intrigued. Reducing irritability or reaching is liberating as a goal in and of itself.Via Lee Vinsel, a paper: "a stupidity-based theory of organizations" by Mats Alvesson and André Spicer.

....

Negative capability, as it’s been widely interpreted, suggests a uniquely human capacity for living with and tolerating ambiguity and paradox and opens a space for counterintuitive non-action.

So, what is this capability that is negative and yet a source of ‘tolerance’, ‘openness’, acceptance of mystery, uncertainty and doubt. Is it a skill, a gift, an ability or something altogether different?

Donella Meadows, the doyen of systems dynamics speaks of it indirectly in her paper Dancing with Systems, when she urges us to stay humble and stay a learner in the face of complexity and uncertainty; “the uncertainty exposed by systems thinking is hard to take. If you can’t understand, predict and control, what is there to do”? and “in a world of complex systems it is not appropriate to charge forward with rigid, undeviating directives. “Stay the course” is only a good idea if you’re sure your on course”.

In this paper we question the one-sided thesis that contemporary organizations rely on the mobilization of cognitive capacities. We suggest that severe restrictions on these capacities in the form of what we call functional stupidity are an equally important if under-recognized part of organizational life. Functional stupidity refers to an absence of reflexivity, a refusal to use intellectual capacities in other than myopic ways and avoidance of justifications. We argue that functional stupidity is prevalent in contexts dominated by economy in persuasion which emphasizes image and symbolic manipulation. This gives rise to forms of stupidity management that repress or marginalize doubt and block communicative action. In turn, this structures individuals’ internal conversations in ways that emphasize positive and coherent narratives and marginalize more negative or ambiguous ones. This can have productive outcomes such as providing a degree of certainty for individuals and organizations. But it can have corrosive consequences such as creating a sense of dissonance among individuals and the organization as a whole.

... We think that the term ‘functional stupidity’ might be evocative and resonate with the experiences of researchers, practitioners, citizens and consumers. Thus, our approach may help to illuminate key experiences of people in organizations, that often are masked by dominant modes of theorizing which emphasize ‘positive’ themes, such as leadership, identity, culture, learning, core competence, innovation and networks. It should open up space for further in-depth empirical investigation of this topic.

The Festival of Maintenance will run on Saturday 10th October 2020, in Liverpool.

This was a week in which I attended an event where an organiser commented that the corporate attendance was low, as many were already being hit by reduced travel policies related to coronavirus.

What are the best ways to run an online event? Janet Gunter prompted me to wonder about this, as did my conversation with Cambridgeshire Climate Emergency. Zoom has quite a lot of in-built support for smaller events but there must be other options out there. (I still recall remotely attending the 2008 Sakai conference, with University of Michigan support for Second Life so we had a 'corridor track' as well as live video streams from the sessions. Second Life is less of a thing, now; it would seem sad if we've regressed in terms of remote event tech though!) I'll be collecting some ideas for this with ClimateAction.tech in the coming weeks.

A bit late, as it's been 2020 a while now - I finished reading the Well's State of the World and wrote up some notes. Some of the bits that stood out for me were Bruce Sterling's thoughts on the world at large; some the state of making.

"Boris" is the equivalent for setting goals of the "negotiated joining" method of hiring for uncertain situations (mentioned last week).

If the environment changes in unpredictable ways, inherently static goals don’t work. If the aim is to create something no one has created before, realistic and achievable goals don’t work.This focus on tradeoffs reminds me of some of the aspects of TechTransformed, Doteveryone's responsible innovation programme for tech businesses. (If you are trying to set up an organisation or product team or accelerator to create digital technologies right, you should be calling Doteveryone and getting the right processes in place with their help.)

Organizations need a fundamentally different way to think about setting and managing goals if they’re facing uncertainty from the environment or from their pursuit of innovation.

So Boris begins from a fundamentally different place.The foundational difference is acknowledging that innovation and uncertainty make it impossible to predict in advance what the “correct” goals for an organization will be. ...

Boris does this by forcing people in teams to talk about the tradeoffs they are (or aren’t) willing to make, instead of focusing on figuring out concrete goals in advance as conventional goalsetting does.

A nice readable paper from two thoughtful Cambridge institutions - the Institute for Manufacturing, and the Bennett Institute for Public Policy - about how we may be misunderstanding manufacturing levels in the UK because of the way industry is counted and classified.

It's hard to disprove some fears about technology surveillance. Via a convoluted Twitter thread, an academic study into whether Android phones are listening to their users.

Precious Plastic's recycling system has launched their v4 system, a big step forward with

It's fifty years since the first national women's liberation conference in Oxford; papers on childcare, women's employment, etc, still relevant today.

And finally Danny O'Brien with a lovely little thread that I very much relate to.

|

| https://twitter.com/mala/status/1233254419833094150 |