Weeknotes: mutual aid, PPE, open hardware, safety, AI

It's been a week since my last weeknotes. It felt a long one, and by half way through I wondered if I already had more than enough notes for the week. Luckily a lot of what I thought I'd learned is already out of date; this is still quite long, but rest assured it's not all pandemic response here. Skip ahead if you want content about robots, AI and history instead.

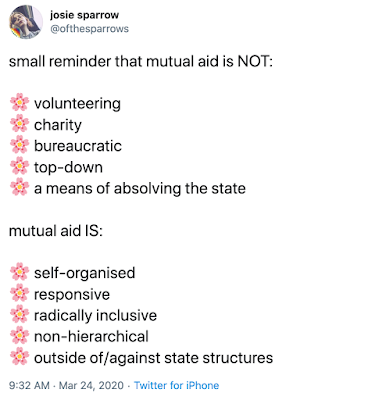

I hope I've been being somewhat useful this week; it feels like you should be useful now, if you can be. I've distributed parish council leaflets, because local mutual aid matters (or you can volunteer for the NHS or the national care force.) I've also been working online, hopefully in areas where I have some useful experience and skills.

It's such an incredible privilege to be able to stay home, to be able to

volunteer to do anything, to be connected online, when so many others

must work or care or struggle.

People need a lot of help right now. Here's the Citizens Advice dashboard with the dip showing when everyone was watching the PM's announcement on the 23rd March:

Luckily there are many people being kind; thanks to Mevan Babakar for collecting these.

There's echoes of the local humanitarian manufacturing which is the heart of Field Ready, just with none of the humanitarian response coordination you would normally get from UNOCHA and the established ways of working in crisis of the aid sector, across government and civil society and communities. (Thanks to Cat Ainsworth for outlining how this might look.)

The high level of demand for PPE in the UK is evident in all kinds of ways. This demand comes from hospitals of course, but also primary care, dentists, care homes and agencies, workplaces with a lot of people contact (essential shops, prisons) and high risk environments (undertakers), not to mention individual carers, plus households. And in the maker and manufacturing communities the enthusiasm to supply can be seen all over social media with people designing, making and experimenting with cloth masks, filters, face shields and more. How many projects to make things are actually connecting with the desperate pleas for supplies? There are also now more pleas for materials, as the volume of PPE required - even with unusually high levels of reuse or long wear - is very high.

The serious engineering projects happen behind the scenes, only being announced when they get good results - such as UCL's recent collaborative work on CPAP (non-invasive ventilators). Low tech PPE seems to be still out in the cold, with little visible active central coordination.

There are still a multitude of projects out there in this space - even if I look just at UK PPE. I decided a week ago to put some effort behind HelpfulEngineering.org, which was getting good momentum after only a couple of weeks of existence, with over 12,000 people from around the world in the Slack group when I joined. One interesting feature of this group is that it seeks to ensure designs are appropriately tested, and that claims made in comms and PR are reasonable. This more responsible engineering practice is appealing in such a noisy and fast-moving time. It's a very decentralised group, using swarm organising, and has all the challenges you would expect of such a thing in a rapid growth scenario, and whilst there are official projects and structures there's also a lot of chaos. I've spent some of the week trying to help, aggregating information on cloth face masks and for face shields, so these spaces are easier to navigate, and bridging between various communities working both locally in Cambridgeshire and nationally/internationally, as far as possible.

The lack of coordination in the UK, which has different challenges for demandside logistics than other countries, lead to a few of us bringing together a new group to try to see if there was anything we could do to smooth the paths of both those needing PPE and trying to make it here. We'll see whether this can be a useful effort. Mostly I've been moving small bits of information from one place to another - "if you don't get help here, try over there," or "you might want to think about the fit of that mask, here's some notes from other people who have been testing them." One challenge is to separate local from global more clearly. There will be a global set of, say, open source cloth face mask designs. Some will work better in some regions - primarily due to material availability, as much or more than manufacturing facility and skills availability. Specific hospitals or other specialist users will have their own requirements, based on national standards, and local setting needs (this might include issues of fit, cleaning/replacement, and so on, not just quality of filter or whatever). It's a lot harder to establish what organisations need what equipment, than to find a plethora of keen makers with 3D printers on standby, sadly. I doubt overloaded care homes are posting their needs on Twitter. Rough estimates of how much PPE might be needed in the UK get you to big numbers fast, whether you are following Matt Hancock's announcements, or doing back of the envelope calculations. We may well need microscale manufacture (when done with care, with suitable workspaces and precautions, such as is happening at Makespace) as well as repurposed factories.

It's hard to resist the urge to clutch at technical coordination solutions, when so much of supply chain work is about relationships. Vicki Boykis writes a bit about PPE and some of the US response and I was struck by this:

Via The Prepared community, a note that air freight costs are increasing as capacity drops. Also:

Nick Hunn writes about some of the UK manufacturing issues for ventilators:

Open hardware is coming into its own now. Via Tobias Wenzel, a preprint describing diverse free and open source scientific and medical responses to the crisis. HardwareX is putting together a special issue on open hardware for pandemic response too.

IP and coronovirus response - thanks to Frank Tietze for highlighting the need for new thinking around commercial intellectual property at this time. I was pleased to see moves to open standards for some products in Europe. There's also a pledge where companies can commit to opening up their IP during the crisis: opencovidpledge.org The Prusa 3D printed face shield design, which has proved very popular and certainly has excellent documentation and files available, is under a non-commercial licence, which might affect some users. It certainly deters some reuse. Don't use CC-NC, folks, unless you are really clear why you are doing it.

Kathryn Corrick has been thinking about video conferencing - and what a mess so many of the tools we are using today are, between privacy and security and pricing and access. She thinks we might need to look at open standards (again).

A helpful reminder from Lydia Nicholas at Doteveryone that we still need responsible technology, even amidst the crisis.

It's going to be interesting to see which companies and organisations can adapt to all of this. It's intriguing to see who is organising to respond, in whatever way, and which organisations seem silent.

Michael Feldstein at eLiterate has written about resilience in crisis; this is mostly driven by thinking about education, but I found the 2x2 in the middle really helpful as a way to structure the needs for other kinds of information resource, too:

David Runciman in the LRB on the timeliness or otherwise of political response, and how voters may judge today's leaders.

Starsky Robotics were trying to make software-driven trucks. It didn't work, and Stefan Seltz-Axmacher has written a terrific article on why.

In similar vein, Aaron Gordon writes in Vice on tech innovation and history, with lots of familiar historians quoted.

Via Christopher Markou, Jaron Lanier and Glen Weyl on AI. The details on Taiwan's participatory govtech work over the years and its impact now on coronavirus are particularly worth reading (although I'm not highlighting them here).

I appreciated Sentiers reminding me of just a year ago, and a Q&A with Jenny Odell about why doing nothing is the best self-care in the internet era. Seems timely, now.

For fun, you can now download the Boardgame Remix Kit for free, to make more entertainment from your existing game sets. Now Play This will take play next weekend online; different to the beautiful setting of Somerset House, but undoubtedly still creative and playful.

Last Friday a team of us took part in Coney's Back (after this break) which was super, and much to our surprise, we won. There will be future Remote Socials from Coney, too.

I hope I've been being somewhat useful this week; it feels like you should be useful now, if you can be. I've distributed parish council leaflets, because local mutual aid matters (or you can volunteer for the NHS or the national care force.) I've also been working online, hopefully in areas where I have some useful experience and skills.

|

| https://twitter.com/ofthesparrows/status/1242383687926329351 |

People need a lot of help right now. Here's the Citizens Advice dashboard with the dip showing when everyone was watching the PM's announcement on the 23rd March:

Luckily there are many people being kind; thanks to Mevan Babakar for collecting these.

There's echoes of the local humanitarian manufacturing which is the heart of Field Ready, just with none of the humanitarian response coordination you would normally get from UNOCHA and the established ways of working in crisis of the aid sector, across government and civil society and communities. (Thanks to Cat Ainsworth for outlining how this might look.)

The high level of demand for PPE in the UK is evident in all kinds of ways. This demand comes from hospitals of course, but also primary care, dentists, care homes and agencies, workplaces with a lot of people contact (essential shops, prisons) and high risk environments (undertakers), not to mention individual carers, plus households. And in the maker and manufacturing communities the enthusiasm to supply can be seen all over social media with people designing, making and experimenting with cloth masks, filters, face shields and more. How many projects to make things are actually connecting with the desperate pleas for supplies? There are also now more pleas for materials, as the volume of PPE required - even with unusually high levels of reuse or long wear - is very high.

The serious engineering projects happen behind the scenes, only being announced when they get good results - such as UCL's recent collaborative work on CPAP (non-invasive ventilators). Low tech PPE seems to be still out in the cold, with little visible active central coordination.

There are still a multitude of projects out there in this space - even if I look just at UK PPE. I decided a week ago to put some effort behind HelpfulEngineering.org, which was getting good momentum after only a couple of weeks of existence, with over 12,000 people from around the world in the Slack group when I joined. One interesting feature of this group is that it seeks to ensure designs are appropriately tested, and that claims made in comms and PR are reasonable. This more responsible engineering practice is appealing in such a noisy and fast-moving time. It's a very decentralised group, using swarm organising, and has all the challenges you would expect of such a thing in a rapid growth scenario, and whilst there are official projects and structures there's also a lot of chaos. I've spent some of the week trying to help, aggregating information on cloth face masks and for face shields, so these spaces are easier to navigate, and bridging between various communities working both locally in Cambridgeshire and nationally/internationally, as far as possible.

The lack of coordination in the UK, which has different challenges for demandside logistics than other countries, lead to a few of us bringing together a new group to try to see if there was anything we could do to smooth the paths of both those needing PPE and trying to make it here. We'll see whether this can be a useful effort. Mostly I've been moving small bits of information from one place to another - "if you don't get help here, try over there," or "you might want to think about the fit of that mask, here's some notes from other people who have been testing them." One challenge is to separate local from global more clearly. There will be a global set of, say, open source cloth face mask designs. Some will work better in some regions - primarily due to material availability, as much or more than manufacturing facility and skills availability. Specific hospitals or other specialist users will have their own requirements, based on national standards, and local setting needs (this might include issues of fit, cleaning/replacement, and so on, not just quality of filter or whatever). It's a lot harder to establish what organisations need what equipment, than to find a plethora of keen makers with 3D printers on standby, sadly. I doubt overloaded care homes are posting their needs on Twitter. Rough estimates of how much PPE might be needed in the UK get you to big numbers fast, whether you are following Matt Hancock's announcements, or doing back of the envelope calculations. We may well need microscale manufacture (when done with care, with suitable workspaces and precautions, such as is happening at Makespace) as well as repurposed factories.

It's hard to resist the urge to clutch at technical coordination solutions, when so much of supply chain work is about relationships. Vicki Boykis writes a bit about PPE and some of the US response and I was struck by this:

it’s interesting that Petersen discounts human relationships in the supply chain since it seems like the only way the city got those masks is because he reached out to the city.I've now been asked to help HelpfulEngineering with organisational design, perhaps as my skills might add more value there, so hopefully others in the community will be able to assist in the ongoing hour by hour labour of maintaining READMEs.

Via The Prepared community, a note that air freight costs are increasing as capacity drops. Also:

China has ramped up N95 mask production 2,000% since the beginning of February. This has put a lot of stress on the supply chain for melt-blown fabric, the synthetic textile used in the masks, raising wholesale prices from $6,000 to $60,000 per ton.

Nick Hunn writes about some of the UK manufacturing issues for ventilators:

There was a report this week from the High Value Manufacturing Catapult claiming that five design companies have been asked to write a specification and the best one will be chosen by PA Consulting. The Government currently has a policy of funding development through competitions, typically run by Innovate UK. This feels like a rerun of that approach. It doesn’t chime with the current imperative, which needs a cooperative effort which pools the best available talent. This should not be treated like an Innovate UK competition, but a collaborative national effort.There's a great thread on the different ways you might get more oxygen in a hospital setting, up to and including how invasive ventilators work.

Yesterday (Friday 20th March) BEIS published a specification for a “rapidly manufactured ventilator system”, with the intention of acquiring 30,000 units. Nothing indicates whether this is the “winner” of the process reported by the High Value Manufacturing Catapult, or an amalgam of inputs. It’s a good overview, with some very pragmatic requirements, such as:

It must be intuitive to use for qualified medical personnel, but these may not be specialists in ventilator use,

It must not require more than 30 minutes training for a doctor with some experience of ventilator use, and

Instructions for use should be built into the labelling of the ventilator, for example, with ‘connect this to wall’ etc.

These imply that BEIS realises that many of the people using it will have minimal background experience. The specification is obviously a little rushed, as it includes the statement “Need the advice of an electronic engineer with military/resource limited experience before specifying anything here. It needs to be got right first time.” However, it’s honest and has a sensible section on unknown issues.

Open hardware is coming into its own now. Via Tobias Wenzel, a preprint describing diverse free and open source scientific and medical responses to the crisis. HardwareX is putting together a special issue on open hardware for pandemic response too.

IP and coronovirus response - thanks to Frank Tietze for highlighting the need for new thinking around commercial intellectual property at this time. I was pleased to see moves to open standards for some products in Europe. There's also a pledge where companies can commit to opening up their IP during the crisis: opencovidpledge.org The Prusa 3D printed face shield design, which has proved very popular and certainly has excellent documentation and files available, is under a non-commercial licence, which might affect some users. It certainly deters some reuse. Don't use CC-NC, folks, unless you are really clear why you are doing it.

Kathryn Corrick has been thinking about video conferencing - and what a mess so many of the tools we are using today are, between privacy and security and pricing and access. She thinks we might need to look at open standards (again).

A helpful reminder from Lydia Nicholas at Doteveryone that we still need responsible technology, even amidst the crisis.

It's going to be interesting to see which companies and organisations can adapt to all of this. It's intriguing to see who is organising to respond, in whatever way, and which organisations seem silent.

Michael Feldstein at eLiterate has written about resilience in crisis; this is mostly driven by thinking about education, but I found the 2x2 in the middle really helpful as a way to structure the needs for other kinds of information resource, too:

|

| from https://eliterate.us/resilience-network-resources/ |

Starsky Robotics were trying to make software-driven trucks. It didn't work, and Stefan Seltz-Axmacher has written a terrific article on why.

There are too many problems with the AV industry to detail here: the professorial pace at which most teams work, the lack of tangible deployment milestones, the open secret that there isn’t a robotaxi business model, etc. The biggest, however, is that supervised machine learning doesn’t live up to the hype. It isn’t actual artificial intelligence akin to C-3PO, it’s a sophisticated pattern-matching tool.The diagrams are great, here.

The S-Curve here is why Comma.ai, with 5–15 engineers, sees performance not wholly different than Tesla’s 100+ person autonomy team. Or why at Starsky we were able to become one of three companies to do on-public road unmanned tests (with only 30 engineers).Highlights mine:

To someone unfamiliar with the dynamics of venture fundraising, all of the above might seem like a great case to invest in Starsky. We didn’t need “true AI” to be a good business (we thought it might only be worth ~$600/truck/yr) so we should have been able to raise despite the above becoming increasingly obvious. Unfortunately, when investors cool on a space, they generally cool on the entire space. We also saw that investors really didn’t like the business model of being the operator, and that our heavy investment into safety didn’t translate for investors.

....

While trucking companies don’t know how to buy safety critical robots, they do know how to buy trucking capacity. Every large trucking company does so — their brokerages buy capacity from smaller fleets and owner-operators, many of whom they keep at an arm’s length because they don’t know how much to trust their self-reported safety metrics. At Starsky we found 25+ brokers and trucking companies more than willing to dispatch freight to trucks they already suspected were unmanned. While this is a lower margin business than software’s traditional 90%, we expected to be able to get to a 50% margin in time.

It took me way too long to realize that VCs would rather a $1b business with a 90% margin than a $5b business with a 50% margin, even if capital requirements and growth were the same.

... No One Really Likes Safety, they like Features

.... The problem is that people are excited by things that happen rarely, like Starsky’s unmanned public road test. Even when it’s negative, a plane crash gets far more reporting than the 100 people who die each day in automotive accidents. By definition building safety is building the unexceptional; you’re specifically trying to make a system which works without exception.

Safety engineering is the process of highly documenting your product so that you know exactly the conditions under which it will fail and the severity of those failures, and then measuring the frequency of those conditions such that you know how likely it is that your product will hurt people versus how many people you’ve decided are acceptable to hurt.Doing that is really, really hard. So hard, in fact, that it’s more or less the only thing we did from September of 2017 until our unmanned run in June of 2019. We documented our system, built a safety backup system, and then repeatedly tested our system to failure, fixed those failures, and repeated.

The problem is that all of that work is invisible. Investors expect founders to lie to them — so how are they to believe that the unmanned run we did actually only had a 1 in a million chance of fatality accident? If they don’t know how hard it is to do unmanned, how do they know someone else can’t do it next week?

Our competitors, on the other hand, invested their engineering efforts in building additional AI features. Decision makers which could sometimes decide to change lanes, or could drive on surface streets (assuming they had sufficient map data). Really neat, cutting- edge stuff.

Investors were impressed. It didn’t matter that that jump from “sometimes working” to statistically reliable was 10–1000x more work.

In similar vein, Aaron Gordon writes in Vice on tech innovation and history, with lots of familiar historians quoted.

“Tech, historically, has been deeply uninterested in looking backwards,” said Margaret O’Mara, a history professor at the University of Washington and the author of The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America, a history of Silicon Valley. When tech companies do invoke history, she pointed out, it’s often closer to mythology. Consider the Tale of Two Steves of Apple in a garage. Otherwise, as she asked rhetorically in the book’s introduction, “Why care about history when you’re building the future?”

This anti-history bias is not merely a curious quirk of a group of people that has drastically shaped the modern world. It is a foundational principle....

But O’Mara argues that this altar of progress is a distortion of what really made Silicon Valley what it is. “When you actually study history,” O’Mara said, “things get really messy really fast.” None more so than the history of the tech industry itself.

... This is partly why O’Mara thinks we’re at the beginning of a shift in which Silicon Valley will start to care about history. ... The industry is now mature enough that parts of it are history itself.

But it’s not mere nostalgia—or, less charitably, a different form of hubris—that makes history important. Even historians disagree on why history matters. Some stress that its cyclical nature—“history doesn’t repeat itself but it rhymes”—is the business case for learning history, so one does not repeat the mistakes of the past.

There’s something to this, but history’s relevance runs deeper. Learning it can be almost spiritual, a kind of therapy. It’s oddly comforting to learn about times when people thought they were experiencing unprecedented circumstances, when they were scared out of their minds about what had become of their society, when they were afraid they had lost all control over events. Things may be different today, but not that different.

History does a lot of telling us what we don’t want to hear. It disposes of the progress myth we are taught in schools...that things just keep getting better, even as it feels like they are only getting worse.

Via Christopher Markou, Jaron Lanier and Glen Weyl on AI. The details on Taiwan's participatory govtech work over the years and its impact now on coronavirus are particularly worth reading (although I'm not highlighting them here).

After all, the term "artificial intelligence" doesn’t delineate specific technological advances. A term like “nanotechnology” classifies technologies by referencing an objective measure of scale, while AI only references a subjective measure of tasks that we classify as intelligent. For instance, the adornment and “deepfake” transformation of the human face, now common on social media platforms like Snapchat and Instagram, was introduced in a startup sold to Google by one of the authors; such capabilities were called image processing 15 years ago, but are routinely termed AI today. The reason is, in part, marketing. Software benefits from an air of magic, lately, when it is called AI. If “AI” is more than marketing, then it might be best understood as one of a number of competing philosophies that can direct our thinking about the nature and use of computation.Categorisation harms in 'tech 4 good' by Kate Sim and Margie Cheesman is a helpful short read. Categorisation is often harmful.

.... A clear alternative to “AI” is to focus on the people present in the system. If a program is able to distinguish cats from dogs, don’t talk about how a machine is learning to see. Instead talk about how people contributed examples in order to define the visual qualities distinguishing “cats” from “dogs” in a rigorous way for the first time.

.... Supporting the philosophy of AI has burdened our economy. Less than 10 percent of the US workforce is officially employed in the technology sector, compared with 30–40 percent in the then leading industrial sectors in 1960s. At least part of the reason for this is that when people provide data, behavioral examples, and even active problem solving online, it is not considered “work” but is instead treated as part of an off-the-books barter for certain free internet services. Conversely, when companies find creative new ways to use networking technologies to enable people to provide services previously done poorly by machines, this gets little attention from investors who believe “AI is the future,” encouraging further automation. This has contributed to the hollowing out of the economy.

.... Indeed, recent research has shown that without the human-created Wikipedia, the value of search engines would plummet (since that is where the top results of substantial searches are often found), even though search services are touted as frontline examples of the value of AI. (And yet the Wikipedia is a thread-bare nonprofit, while search engines are some of the most highly valued assets in our civilization.)

... gender assumptions are constructed and reinforced in the way that data is encoded in the system design. For example, users are asked to define their experience by selecting a category of violence from a prefigured list that includes categories like ‘sexual harassment’ and ‘verbal abuse.’ The implicit assumption here is that these categories are self-evident and well-defined. Yet, analysing users’ experiences searching for the ‘right’ category demonstrates how these reporting tools’ categories--as a constructed system of defining and sorting—fall short in capturing a range of users’ experience of sexual misconduct.

I appreciated Sentiers reminding me of just a year ago, and a Q&A with Jenny Odell about why doing nothing is the best self-care in the internet era. Seems timely, now.

For fun, you can now download the Boardgame Remix Kit for free, to make more entertainment from your existing game sets. Now Play This will take play next weekend online; different to the beautiful setting of Somerset House, but undoubtedly still creative and playful.

Last Friday a team of us took part in Coney's Back (after this break) which was super, and much to our surprise, we won. There will be future Remote Socials from Coney, too.