Weeknotes: climate, algae, planning, hearables, fun

The wonderful denizens of ClimateAction.Tech have collaborated on a new magazine, because:

According to Nature, even before we pivoted to our screens so fully in 2020, uptake, information and communications systems accounted for two per cent of the world’s carbon emissions. The authors point to the music video for the hit song “Despacito” by Luis Fonsi feat. Daddy Yankee, which has five billion views on YouTube, and argue that to generate this kind of energy would take either 850,000 barrels of oil or 93 wind turbines running for an entire year. In the first quarter of 2020, Facebook reportedly removed 2.2 billion fake accounts, with each active profile estimated to account for 281 grams of CO2 – the same carbon footprint as a medium latte. And in 2019, the average user living in Europe scrolled the equivalent of 180 meters a day, exposing themselves on average to 1,700 carbon intensive – but ultimately ineffective – banner ads a month.

Branch is about a sustainable internet for all; the editors write: We believe that the internet must serve our collective liberation and ecological sustainability. We want the internet to help us dismantle the power structures that delay climate action and for the internet itself to become a positive force for climate justice. Recommended.

I had not heard (or had forgotten) about POUR - a really useful summary of how to design things for everyone (albeit seemingly ignored in many phone/tablet interfaces these days, thanks Apple and friends):

|

| https://twitter.com/mrchrisadams/status/1321061500811956226 |

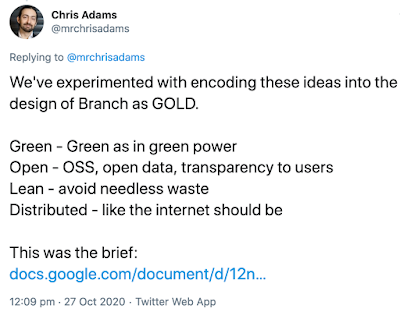

I'm delighted to see Branch and friends pushing this thinking:

|

| https://twitter.com/mrchrisadams/status/1321061507040497665 |

I heard an advert for the Woodland Trust in a podcast this week, which mentioned that tree planting was still our best hope. This seems to elide over a lot of detail - you need to look after the trees, not just plant them, and plant the right kinds in sensible spaces, and so on. So many of the twig-like saplings around new buildings and roads seem more of a cheap gesture towards carbon capture or landscaping than a serious attempt to replace the mature trees destroyed in the earlier stages of work. Anyway, I was interested to read about algae - Benjamin Cooley writes for Parametic Press:

At Davos earlier this year, the World Economic Forum announced a plan to plant one trillion trees over the next decade. The campaign received widespread approval and enthusiasm from attendees, and even received backing from President Trump through a recent executive order to promote tree planting. (This may seem surprising coming from the man who notoriously withdrew the US from the Paris Agreement on global climate action.)

But as we’ll see, the possibility of even planting a trillion trees may be more of a political pipedream than an achievable reality.

... Trees, and plants in general, are very good at the removing CO₂ part of our fight against irreversible climate change. Many people categorize this as a viable carbon sequestration method. But there’s a problem with planting a trillion trees: we first need the amount of land to do it. We also need to keep them alive long enough to help us.

... Best case estimates show that it will take around 25 years before the amount of carbon sequestered matches the amount of carbon emissions for a single person’s share on a single flight (some trees can take up to 100 years to mature fully). So while the strategy may be effective, it won’t help us much in the ~10 years estimated by the IPCC that we have left to prevent irreversible changes to the climate.

... The United Kingdom has pledged to reach net zero emissions by 2050. A report this year found that in order to reach that goal, the UK would need to commit 20% of its current farmland to dedicated carbon capture and storage uses. And to have a chance at reaching their targets, they need to start doing that, more or less, right now.

Converting farmland is not an isolated effort either: Reducing traditional crops by around 20% means the government will also count on people to adopt low-carbon farming practices, reduce food waste, and make diet changes described as “a 20% shift away from beef, lamb and dairy to alternative protein sources.”

... On top of all this, if somehow we did find the 1.7bn hectares of suitable land to plant these trees, we would also need to protect them. When trees die, they release all the CO₂ they have eaten up back to the atmosphere. Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest rose by nearly 30% in 2019. On the other side of the globe, bushfires in Australia emitted nearly half of the country’s annual emissions—and that’s on top of Australia’s usual CO₂ output.

... You’ve probably seen algae before—it’s floating about on ponds and washing up on shores as kelp seaweed. It takes many different forms, though. Algae can be as small as 0.2mm in picoplankton and as large as 60m long in the form of giant sea kelp. And incredibly, when you take all the types of algae together, this family of flora produces about half of all oxygen on the planet.

... Due to its size and composition, algae excels at a special type of carbon removal method called bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). This means that researchers are studying two things: 1) how we can use algae to remove carbon and 2) how we can use the captured carbon for something else, such as fuel, food, and heat. ... Regardless of being a less-developed research solution, scientists agree that in the long term BECCS is no longer an optional piece to solving the climate crisis.

The article goes on to describe the benefits of algae as a carbon removal techology, albeit one at an earlier research and development stage - but algae work fast, grow in all kinds of places, and don't need the land or water commitment of trees.

Hmm:

|

| https://twitter.com/agentGav/status/1321791184335970304 |

Dan Stone from the Centre for Sustainable Energy writes (in July) about a review of Local Plans:

Nearly 70 % of local councils have now declared a climate emergency, and many have set 2030 as a date for going zero-carbon, 20 years ahead of central government’s 2050 target.

The planning system has crucial role to play in delivering effective action on climate change: it is the gatekeeper that allows renewable energy projects to go ahead and regulates how our built environment is constructed. It is also the only mechanism through which the spatial aspects of decarbonisation and climate adaptation can be addressed. So while the Climate Change Act legally commits us to net zero emissions by 2050, this will be achieved only if we plan for it; hence the question: are Local Plans actually planning for the zero-carbon future we need?

... most of the Local Plans we reviewed needed significant changes in order to address the climate crisis adequately. Most Local Plans do not acknowledge quite how radical and challenging the 2050 zero-carbon commitment is for planning and place-making. Indeed, the implications for planning beyond binding zero-carbon standards for new builds are dramatic enough to warrant listing here, and include:

- A significant modal shift (and reallocation of road space) to cycling, walking and public transport, and a significant overall reduction in vehicle miles – this will require a wholescale re-imagining of development patterns and layouts based on presumed access on foot, by bike and by public transport, rather than by car. (See, for example, the research CSE undertook for Bristol City Council.)

- Widespread electric vehicle charging networks, to allow petrol or diesel vehicles to be phased out.

- A quadrupling of renewable energy capacity.

- Energy efficiency upgrades to nearly all our building stock, including listed and historic buildings, public and private.

- The removal of gas boilers, to be replaced with district heating network connections and heat pumps.

Climate change declarations targeting net zero emissions by 2030 necessitate doing all this in the next ten years.

... Only two plans that we saw were carbon audited and set out carbon budgets. Fewer than half of the others mentioned carbon emissions at all. Where they did so, it was in general rather than specific terms, and the councils involved did not set out a carbon budget for their district, or quantify the impact of their policies on their emissions. This is important because you can only know your progress in reducing emissions if you are measuring them in the first place.

... Only a third of the Local Plans reviewed (all from ‘core cities’) had binding zero-carbon policies or objective standards for energy efficiency or carbon dioxide emissions. The remainder either had no policies at all for reducing emissions from buildings, or merely supportive policies, encouraging ‘high levels of energy efficiency’... many rural authorities just don’t have these resources and are struggling to keep up.

Interesting in this context is the Future Homes Standard, which threatens to remove the discretion of local authorities to go beyond building regulations and impose zero-carbon policies – as many core cities have. National regulation is clearly the way to go, but only if it is strong enough and actually requires new development to be net zero-carbon. The Future Homes Standard should be a floor for those authorities struggling to keep up, rather than a ceiling constraining what the most ambitious authorities are doing to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from new development.

... In the majority of Local Plans, climate adaptation related predominantly, or even solely, to flooding. Only half contained an overheating policy, and not all of these set out criteria and a specific methodology against which overheating was to be assessed. Only half of the Local Plans made the link between flooding or overheating and the provision of green infrastructure, and only a couple committed to increasing tree cover.

The FT this weekend[paywall] reviewed Google's latest wireless earphones (earbuds? I dunno) the Pixel Buds and reckoned that the simultaneous translation of maybe 40 languages was 80-95% good. That's a startlingly high level of usability to my mind - I hadn't realised consumer audio in/audio out translation had got that good. Nick Hunn's latest review of the hearables space notes that wireless headphones are really booming this year, but also that hearing aid sales are desperately low

Thinking of and reasoning about plausible and useful futures is hard. I like the simplicity of some of the work from the Near Future Laboratory - I have a lovely catalogue from some years ago - which manages to be very thought-provoking in unexpected ways. Another example is the transport map of Geneva described in this talk write up by Fabien Girardin.

Building real stuff is hard:

|

| https://twitter.com/iotwatch/status/1321526648383115265 |

Thought-provoking thread from Katja Bego (especially the bits with Tom Forth) about tech jobs, pay, access, and tech for good - or bad.

Research into young people’s attitudes to democracy - and the role of populists around the world - in a fascinating edition of Talking Politics podcast. I usually think I don't like podcasts, and perhaps I don't, but I am enjoying TP lately. Maybe its signal to noise ratio is better than most others I've encountered.

Is the thing people miss when stuck at home fun? The highlights here aren't the most amusing bits of Rachel Sugar's piece in Vox I'm afraid. Finding unexpected moments of playfulness has been, well, fun, in lockdown for me.

“Are you fun?” I wonder, staring at focaccia recipes on the internet. Is Emily in Paris fun? Is a Zoom birthday party fun, is ordering a pizza fun, are jokes fun, is wine fun? Have I ever experienced fun? Seven months into the Covid-19 pandemic, I have lost track.

... There is surprisingly little research about the precise nature of fun, given how much we all apparently enjoy it. There is robust and growing literature on overlapping topics — happiness, pleasure, leisure, flow — but fun itself is rarely discussed as such, except in books for children.

... He loves heavy metal rock concerts, and his wife loves reading in solitude, and both of them are experiencing what Rucker would classify as fun. “What’s so awesome about fun,” he explains, quite seriously, “is that it’s unique to the individual,” which may explain the dearth of literature about it. “Happiness has been boiled down to these survey instruments, where we can fill out bubbles on a Scantron, and then the positive psych gurus of the world can tell us whether or not we’re happy. But fun is meant to be owned by you.”

... Unless you really put some muscle in (take a bubble bath?), nothing is conveniently novel, nothing is effortlessly social, and very little is spontaneous, which is another factor in Oh’s theory of fun.

... Until mid-March, I hadn’t realized how much of what I did was possible because I had the freedom and resources to get out of the house. I would have said I didn’t do much, but in fact, I did things all the time. I went to the gym and sat in coffee shops and browsed in bookstores and in drugstores and in stores selling “home goods,” and so much of what read to me as fun was in fact commercial leisure, which I’d depended on for formal permission not to work.

A long read on deep friendships by Rhaina Cohen.

How normal am I? A nice illustration of the scary potential of facial systems. Belated thanks to James Smith!