Fortnightnotes: environmentalism, the left, information literacy

So many discussions of inclusion and diversity seem to ignore class, so I appreciated this -

| |||

| https://twitter.com/Anna_Colom/status/1327348323330764800 |

A great article by Tim Carmody covering two different ways people have written about pandemic risks/decisions:

Maddow has constructed a universe where she is a tiny satellite orbiting a much larger planet, whose continued health and existence is the central focus of her concern. Manjoo has drawn a map with himself at its center, where anyone beyond the reach of his telephone falls off the edges.

Maddow is also explicitly pleading with her viewers to learn what they can from her experience, and adjust their behavior accordingly. Manjoo is performing his calculus only for himself; he implicitly presents himself as a representative example (while also claiming he and his circle are extraordinarily conscientious and effective), but each reader can draw their own conclusions and make their own decision.

At this point the balancing dominoes tip over. Maddow’s position, her argument, and her example are clearly more moral and more persuasive than Manjoo’s. His essay is worth reading, but the conclusion is untenable. It doesn’t do the work needed to arrive there or persuade anyone else to do the same. And at a time when many people are spinning conspiracies about the pandemic, or claiming that it’s no big deal, and in turn influencing others, it’s irresponsible.

The larger moral tragedy here is that because our leaders have failed, and too often actually worked to damage the infrastructure, expertise, and goodwill accumulated over generations, we have no consistent, authoritative guidance on what we should and should not do. We do not know who to trust. ... We have no sense of what rules our friends and neighbors, colleagues and workers, are following when they’re not in our sight, or would even admit to or deny embracing.

Lockdowns for thee, but not for me - a collection of examples of powerful people ignoring the rules. HT John Naughton.

Computational thinking considered harmful. Interesting idea from Jon Crowcroft.

Version control for machine learning - replicate.ai. Nice and open source, but did we really not have this sort of thing already?

A review of Envision glasses, which are based on Google Glass, and can read text, describe a scene or find an object. (Link thanks to Terence Eden who was rightfully excited about this; similar to the impressive audio/hearables stuff mentioned last week, it feels this tech has just been coming along nicely without anyone paying attention.)

Adrian McEwen reviews Lo-TEK Design by Radical Indigenism

by Julia Watson.

I had mixed feelings reading this, but I think that's because I'm not really the target audience. I grew up in the countryside, with plenty of exposure to farms. It was really interesting to read about these alternate systems from round the world, and plenty seem under threat from Western ideas about how to "do farming/conservation right" or just the endless appetite of capitalism. If it helps protect any of it, then that's more than enough good for the book. I'm less convinced that there's lots for the UK, for example, to take from it specifically, as our environment is very different—it felt a bit like it was fetishizing the indigenous technologies a bit, and I think we should also be looking to similar traditional, in-touch-with-the-land, long-term tacit knowledge from our own cultures too.I've seen similar fetishisation of indigenous tech before, and the UK context does feel very different; if only that we have no convenient shorthand for the older knowledge in our culture.

A depressing thread about vaccine access and big pharma and intellectual property - thanks to David Palfrey for sharing:

|

| https://twitter.com/nickdearden75/status/1318149953257091072 |

Nick Dearden's full article is worth a read.

Ouch:

|

| https://twitter.com/RussInCheshire/status/1325371673336557568 |

N K Jemisin has some thoughts on what is needed in this long thread

|

| https://twitter.com/nkjemisin/status/1325545838500843524 |

| Plus: |

|

| https://twitter.com/JKSteinberger/status/1313026089489436673 |

Then there's Graeber in a super short provocative video:

|

| https://twitter.com/DoubleDownNews/status/1323930039101128704 |

Whither higher education? Michael Feldstein writes (wrote - earlier this year) about the third wave of Covid hitting universities:

We cannot commit ourselves to the ideal of equal access to quality education for a global population of 7.8 billion people and simultaneously remain committed to the ideal of small in-person seminars as the paragon of quality education. The two are simply incompatible. I am not suggesting that we lower our standards. Rather, I am suggesting—and I believe Paquette is suggesting—that we take a good hard look at how much our standards may be influenced by hidden assumptions of privilege. Why should a “quality education” for the 21st-Century masses look identical to the “quality education” of the 19th-Century elites? Where do these ideas of quality come from? Whose goals do they serve? And what trade-offs do they entail?

The article also quotes Gabriel Paquette:

It is easy enough to conjure a vision of a lost academic paradise where philosopher-kings served as presidents, and departments were semiautonomous cantons. This paradise, the myth continues, was decimated by the irruption of centralized authority, the eclipse of academic [sic] by corporate values, and the corruption brought by private philanthropy and athletics. The only chance for redemption, according to this view, is a restoration of the prelapsarian idyll.

If such an idyll ever existed, its heyday coincided with an age when universities were bastions of race-, gender-, and class-based privilege, with a minute fraction of the population enrolled in higher education. This scholastic arcadia could not withstand the pressures brought by the expansion of access to (and democratization of) higher education, the conversion of universities into vehicles of social mobility, the administration of enormous government contracts and grants, and universities’ newfound status as economic bulwarks of entire communities. The resulting transformation gradually made traditional modes of academic organization obsolete. What replaced this beloved anachronism was not necessarily superior to it. But it was a form of management better suited to the complex, large-scale multiversity.

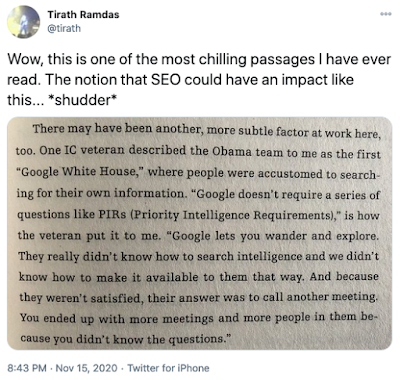

|

| https://twitter.com/tirath/status/1328076285122289664 |

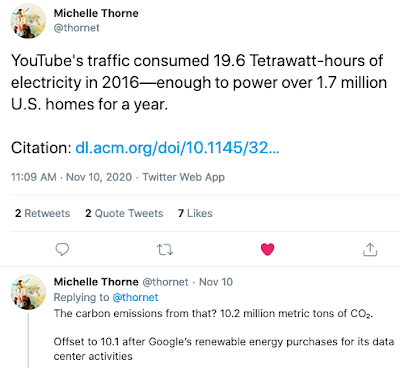

Check the small print - the tiny reduction from Google's data centre renewables buy:

|

| https://twitter.com/thornet/status/1326119739924615170 |

Michelle links to a super article on Parametric Press describing the various carbon consumptions of different online activities.

Charlie Loyd categorises types of environmentalism:

I want to lay out a way I’ve been categorizing kinds of environmentalism. It’s not surprising or clever, and it doesn’t replace any other schemes (like ecocentrism/anthropocentrism, dark/light/bright, or ecomodernism/degrowth). It’s a straightforward retelling of a history that many people know by heart. Plus, it only covers certain movements in mainstream American discourse.

... The first of three categories in this taxonomy might be called the surveyors, to suggest understanding and drawing straight lines from a distance, but also casting a grand kind of gaze, as one surveys an inspiring vista. The surveyor tradition is rooted in romanticism, transcendentalism, and manifest destiny.... Surveyism is concerned with visible purity. ...Surveyism was the dominant kind of published environmentalism (avant le lettre) until about 1960; other kinds of ideas about nature usually posed either as surveyism or as not ideas about nature at all. Because of its long history, its compatibility with established forms of power, and its easily pictured worldview, surveyism remains the primary approach to nature in US culture and law. ...

Another group we might call the neighbors, for their networked worldviews and emphasis on caring and mutualist relationships. As an identifiable movement, the neighbors started in the intersection of the postwar countercultures with biological breakthroughs: in short, second-wave feminism and ecology. One of its hallmarks is a respect for indigenous (i.e., very long-term) human practice, which the surveyor worldview more or less definitionally lacks. This is partly because the neighbors’ philosophy of time is far more sophisticated than the surveyors’ is. The neighbors neither see a philosophical border, nor want a physical border, between human and other-than-human life on Earth. ... Where surveyors are interested in conserving nature by keeping it apart from human space and time, neighbors are interested in sustainable relationships within nature, where individuals, some human, live and die but patterns continue and transform beyond reckoning.

... And finally is an equally loosely connected set of people we might call the stoichiometrists, who only care about carbon. For a stoichiometrist, the surveyors may have delivered us national parks, and the neighbors might have a wonderfully practical solarpunk utopia in mind, but by far the most important environmental issue is that we’re a few years of steady carbon emissions away from a mass extinction that the biosphere will only recover from on geological timescales.

Surveyors and neighbors are arguing about whether parks should allow sustainable wildcrafting while we’re looking at a fair chance that half the species in every park will be wiped out by heat waves and poaching during climate-driven famines. Who cares if a port city plants local trees along the sidewalk? We’re on track for them to be killed by saltwater by the time they’ve each fixed a fraction of a car-year worth of carbon. Surveyism’s estheticization of landscapes and its categorical, deontological, theology-like approach to ethical questions is useless in this crisis. Neighborism’s cozy communities and its caring and virtue ethics are pointed in the right direction but at a fundamentallly smaller scale than the crisis. We are in an emergency. We’re not approaching or planning for an emergency; we’re in it. To address it we need raw, often ugly or philosophically unsophisticated but effective utilitarianism. The only way out is to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere as quickly as possible.

... It should be clear that while I think there are some philosophical valuables worth cutting off surveyism’s corpse, and we could be grateful we got the national parks instead of nothing at all, its main use today is to explain why everything is so badly tainted by colonialism. ... Between the neighbors and the stoichiometrists, I’m more torn. The stoichiometrist argument is simply true as stated. We must quickly retool the global economy or the climate will be a serious disaster everywhere at once. ... You can use both frameworks to think, but when you want to do something, neighborism is ready for you in a way that stoichiometry is not. Neighborism has ideas for things you can do today: build solidarity, improve your own ecological relationships, share knowledge, listen to the marginalized, deepen your understanding of your surroundings, join coalitions to accomplish local goals and build them into regional projects – neighborism doesn’t just suggest responsibilities like these; it starts from them. Will it work in time to save the world? No one knows what that question means. Neighborism is the answer to a different question: What will we do with our opportunities?

|

| https://twitter.com/guyshrubsole/status/1326236178832613376 |

Nick Hunn describes the shocking state of the UK's smart meter programme (and thanks Nick for continuing to call out the dreadful ads from Smart Energy):

Parliament keeps on forcing BEIS to produce updated Impact Assessments, which show the escalating cost of the GB Smart Metering Programme. What these don’t do is ask whether it’s worth stopping and starting again. The current meter specifications were started around the time that Steve Jobs stepped down from Apple, back in 2010. Technology has moved on since then. We are probably at the point where the most cost-effective approach would be to abandon the current smart metering project and replace it with Chinese smart meters for electricity. That would give us a working solution which could be installed by 2025 (especially if the installations were performed by the DNOs and not the energy suppliers) and which would have a 10 – 15 year working life. It will give our cellular network operators the incentive they need to install a country-wide NB-IoT network, which will benefit a host of other connected applications and industries, including Britain’s future in the IoT. We can ignore gas meters, as if we want to hit our net-zero targets, we need to start phasing out gas boilers and replacing them with electric heating, so gas needs to go away within the lifetime of the new smart meters.

This will all cost less than trying to complete the current deployment and mean that we don’t have to keep on paying through the nose for fake news campaigns from Smart Energy GB.

Thanks to Harriet Truscott for bringing more poetry into my Twitter feed:

|

| https://twitter.com/ClaraDaneri/status/1329482875180376068 |