Weeknotes: resistance, microCOVIDs, tinkerers, agrivoltaics

This week saw the launch of "exit to community" - congratulations to everyone involved for making this strong case for a new way for startups to, well, exit, but in a decent way that supports users and workers and makes more sustainable businesses. I also love that it's showcased in a zine. Nathan Schneider writes in Noema (and moots on Twitter that maybe users should seek to buy out TikTok, now :) and even Techcrunch has a nice article about it. At the launch event, there was a great comment about B Corps which I'll be using, because so many people see them as the ultimate solution to less than ethical businesses today: B Corps allow mission to exist, but they don't protect it. Alternative ownership structures do that.

The tale of the FT's investigations into Wirecard[paywall?] is astonishing. Thank goodness we have investigative journalists backed by the funds for the lawyers needed to push through this sort of thing.

I also attended (most of) the 4th annual symposium on the digital person. As usual, this had some excellent provocations, and I enjoyed the networking in yet another online event networking tool (Remo, this time). I think part of the value of the Symposium is that it brings together the legal side and the economics alongside the tech. Some of the best bits:

- We need to switch the question from "what does big tech mean for democracy" to "what does democracy demand from big tech."

- A hypothesis: liberal democracy cannot take on the tech giants, because it would take decades, and there is no appetite for this. So our hope for addressing big tech lies instead with the authoritarian regimes, and we have a model for that in China.

- The outsourcing culture in government has grown over the last 30-40 years. And this seems to have no repercussions.

- Julia Powles asked whether

we are falling into a trap of always saying "if there were to be privacy

requirements on this thing, what might they be?" instead of thinking about

something else, challenging the momentum of the status quo.

- Legal changes from scratch will demand such long timescales, that instead we must reform (including enforcement) and make the best use we can of the legal tools available, because otherwise it's too slow

- My former officemate Heleen Janssen noted that transparency is not the solution, it's part of the problem. You regulate behaviour - that has not changed over time.

I also spotted this new paper about the complexity of data processing in smart homes, by Jiahong Chen, Lilian Edwards, Lachlan Urquhart, Derek McAuley. It's way too long for me but the key issues are really interesting.

Defence Against Dark Artefacts (DADA) addresses smart home cybersecurity risks by identifying strategies for providing security threat management at the edge of the network. This is achieved by screening the behaviour of devices on the network, and detecting when activity is abnormal.

... Edge computing for smart homes holds great promise with its architecture designed to keep the use of personal data inside the home, but it remains unclear whether using such technologies would turn homeowners into liable joint controllers.

Sarah Milstein in LeadDev on how harrassers are often nice to people.

|

| https://twitter.com/F_Kaltheuner/status/1300744233222107136 |

Gig workers work around the system, writes Spencer Soper:

A strange phenomenon has emerged near Amazon.com Inc. delivery stations and Whole Foods stores in the Chicago suburbs: smartphones dangling from trees. ...Who can blame them? Amazon surveills them too, even on social media.

Someone places several devices in a tree located close to the station where deliveries originate. Drivers in on the plot then sync their own phones with the ones in the tree and wait nearby for an order pickup. The reason for the odd placement, according to experts and people with direct knowledge of Amazon’s operations, is to take advantage of the handsets’ proximity to the station, combined with software that constantly monitors Amazon’s dispatch network, to get a split-second jump on competing drivers.

... Much the way milliseconds can mean millions to hedge funds using robotraders, a smartphone perched in a tree can be the key to getting a $15 delivery route before someone else.

... An Uber-like app called Amazon Flex lets drivers make deliveries in their own cars. ... with joblessness rising and unemployment payments shrinking, competition for such work has stiffened, and more people rely on it as their primary income source. Adding to the pressure, fewer people are using ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft, so more drivers have to deliver online shopping orders to make money. As a result, some Whole Foods locations have come to resemble parking lots at Home Depot Inc., where day laborers have long congregated to pick up home repair gigs.

Unlike hourly employees who get paid even when work is slow, gig workers only get paid by the job. So securing a route through the smartphone app is the key first step to making money. Most Flex routes last from two to four hours and can be scheduled in advance. That system can be gamed as well. Drivers download apps on their smartphones that constantly monitor the Amazon Flex site and automatically take any routes that become available, as CNBC reported in February.

... What’s happening at Whole Foods in the Chicago area is different. Drivers are competing for fast-delivery Instant Offers, which require an immediate response and typically take between 15 and 45 minutes to complete. Instant Offers are dispatched by an automated system that detects which drivers are nearby through their smartphones, according to two people familiar with the technology. When drivers see an Instant Offer, they have only a few minutes to accept the delivery or lose it to someone else.

In an urban area with good cell tower coverage and plentiful WiFi hotspots, the system can detect a smartphone’s location to within about 20 feet, one of the people said. That means a phone in a tree outside Whole Foods’ door would get the delivery offer even before drivers sitting in their cars just a block away.

... One reason Flex contractors do this is to get around the requirements for being a driver, such as having a valid license or being authorized to work in the U.S., according to a person familiar with the matter. In such cases, someone who meets the requirements downloads the Flex app and is offered a route earning $18 an hour. He or she accepts the route and then pays someone else $10 an hour to do it, said the person, who requested anonymity to discuss a private matter.

I liked this short thread:

I was pleased to see this funding call prioritising "surveillance and resistance" - the Human Data Interaction Network takes a good stance here, looking at subversion and resistance.

Sarah Gold at Projects by IF is interviewed about new models of collective consent:

At Projects by IF we work with organizations that hold, or are about to hold, lots of data. It’s clear to us that more public value could be derived from commercially held data. But right now that’s hard to do. A big blocker is the way consent works, or rather, doesn’t work. It’s individualized, opaque and tends to be done to people rather than with them.

This is part and parcel of how individualized the world around us, including our technology, has become. Individualism has been the major design principle since the 1970s. It’s even seeped into our data protection frameworks. For example, the European Union’s GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation] provides individualistic rights around data. But data rarely represents just one person.

... Data often represents many people. For example, your DNA represents not just you, but also your family members. ...If you’re a parent, your location data might not be just your location but also your kids’. After all, we’re not fundamentally individuals. We live through relationships with others. So, it shouldn’t surprise us if data about ourselves often represents others too.

… one person is often responsible for managing the thermostat, energy data, and bills, but the energy data represents the activities of a whole household.... Even when data is collected with individual consent, its value is how it can be used for public value. Collective consent is a way to enable greater participation by the communities that are affected by those decisions based on the combined data that’s been collected about them. We think it makes sense for teams working on AI too. Individual models of consent that ask for just-in-time consent aren’t adequate for teams developing machine learning models. Collective consent offers a way to continually innovate with machine learning models and be confident your customers and communities approve of what you’re doing.

In health care they talk about “social licenses” entered into with a community that clearly state what data can be collected, and what it can be used for and why.

This makes the giving of consent a much more deliberative process. Consent would no longer be about an individual facing an “I agree to the terms and conditions” button, but would instead be a conversation with your values, what’s important to you, and what benefit you and others will get from the collection of that info in that way. It brings voices of the community into that process.

... Participation up until now has largely been about round-table discussions. For example, citizen juries. Citizen juries are a tool for engaging citizens on different issues. Typically they involve randomly selected citizens coming together over a number of days to discuss and come to consensus on an issue. In other situations, as an example, consent may require a religious leader to agree that this is a route they should take; permission from the imam might be really important. These participation models need to be culturally competent.

Cultural competence is really important, because you’re more likely to get a diverse, representative cohort if you design with that in mind. Representative cohorts are crucial to design out racism, sexism and ableism from technology.

At IF we’ve been asking what it would look like to have a non-profit group to serve as an intermediary between communities and the organizations that are using their data. The nonprofit might receive a privacy-preserving summary of data from a commercial organization. It could share that summary with the collective which then comments on that data. That could happen through in-app features or in-person activities such as citizen juries that make decisions about how that data can be used.

These are all nascent ideas and need testing.

Calculate the risk of different activities in microCOVIDs (background white paper). 1 microCOVID is a one-in-a-million chance of getting COVID.

Matt Webb also summarises micromorts, and notes that one question about the microCOVID calculator is whether that's for one person or a household.

But there are three distinct reasons why I follow the government lockdown advice:

- risk to my personal/household, which is the focus of the microCOVID project

- risk to others I might meet. I don’t want to accidentally infect my mum, for example

- society a.k.a. public health – we beat this pandemic through collective action, by bringing down Re, the effective reproduction number.

Re isn’t a measure of prevalence. It’s a measure of how easily the virus spreads. It spreads more easily when people are meeting lots of other people without masks; it spreads less easily when social contact is reduced.

If Re is below 1, prevalence decreases; above 1, and it goes up.

I think of society as a whole having an Re budget. The figure I heard, at the beginning of lockdown, was that we needed to reduce in-person social interactions by 75%. I assume that social interactions are the key factor in Re (or at least, were believed to be at the time). Other factors might be: % people wearing masks; proportion of unique vs repeat people encountered.

There are some people we need to spend against the Re budget: health workers, anyone involved in the grocery supply chain, and other key workers. I am happy to reduce my in-person interactions by, say, 90% if that means that key workers need to reduce by only 60%.

Is there a translation between microCOVIDs and Re? I don’t know. Maybe +100 microCOVIDs/week/person in a region with a population density of such-and-such contributes +0.1 to Re.

I’d love to have that connection between personal activity and social good.

... For example, an outdoor restaurant is only 30 microCOVIDs vs 500 indoors. A significant difference! Especially against my weekly budget of 200. Commuting via public transport is out if I want to do anything else.

Useful for figuring out your personal risk options anyway, which is good, because it's hard to keep track of what the legal situation is if you're in a local lockdown area...

Dignity in Dying is calling for a Parliamentary inquiry into end of life choice.

|

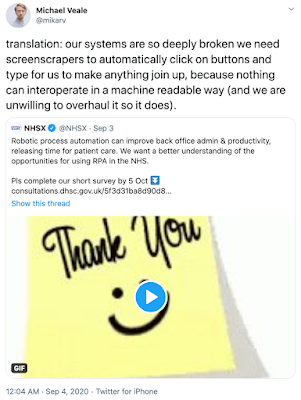

| https://twitter.com/mikarv/status/1301657405126848512 |

A thread about how affordable homes don't always (often?) materialise.

An interesting thread from David MacIver on what roles are currently missing from many (tech) companies.

Tom Spencer on how care and maintenance is your most productive work:

When I was starting out in local government, I used to get frustrated with the people that said, “we did that 10 years ago.” Now I think I am one of those people, and I’m ok with it. ... There seems to be a common belief that to be successful we are required to innovate and change things. I am now beginning to question how true this is, and whether we need to spend a more time caring for and nurturing what we already have.

... Last month a report from the children’s commissioner recommended that the government “develop ‘a national infrastructure’ of children and family hubs that provide a gateway to wraparound support services.” This sounds a lot like the Children’s Centres that were closed up and down the country over the last 10 years. But we cannot now say “let’s invest in Children’s Centres” because Children’s Centres are no longer see as innovative. It would also mean that many local authorities would have to admit that we got it wrong by underinvesting in the ‘old things’ that acted as the cornerstone of the national approach to the early years.

... I am not here to argue that there is no place for innovation. What I will argue is that we overvalue ‘innovate’ ideas and undervalue the care and maintenance required to turn these ideas into real change.

In the same way that we neglect our infrastructure, we too often do not care for and maintain our innovative ideas. We love them when they are new but they get old very fast, especially if they do not deliver change at pace or if there are bumps in the road. We know success is not a linear process but we are too quick to abandon ideas as soon as we are presented with a new shiny idea that has not disappointed us yet and promises to get us to the destination faster.

Turning ideas into meaningful change is mostly about hard work. Your innovation might have planted the seed of an idea, but this is when the real work needs to start.

... Like everyone, I spend a huge chunk of my time doing maintenance and care work. Having 1-to-1s with my team, monitoring the budget, reading internal communications, responding to emails, making sure everyone has done their mandatory compliance training. These are all vital parts of my job but I often feel like I am missing out if I just do ‘maintenance’. It can feel like I am not proving my value or showing my true worth.

On reflection, the work we have done as team to support and maintain the wellbeing of each other is some of the most important work we could have done. We have done innovative work, especially thinking about how we support learning in a virtual environment, but it has been looking after each other than has felt the most vital.

We all do a lot of maintenance work. Do not begrudge it, celebrate it. Make sure you are bringing it up at your 1-to-1s (both as manager of at member of team) and shine a light on the work of the maintainers in your team meetings and other forums. We are all the maintainers!

|

| https://twitter.com/suepritch/status/1300741774202335233 |

A nice article about research into growing crops under Polysolar's mostly-transparent solar panels - agrivoltaics. This work was starting when I worked at Polysolar, and it's exciting to see the paper finally published.

The Cambridge Independent writes about CoFarm.

A useful reminder about how choosing a cloud provider has a notable impact on carbon:

I actually disagree with quite a bit of this article by Luis Perez-Breva - I'm not sure we need more 'tinkerers' or that that is a helpful framing; I suspect the focus on 'capitalist goals' is also unhelpful. But I appreciated his distinction between 'entrepreneurship' and 'speculate-ship' (HT CIVIC Square)

There are now at least three ways to play “entrepreneur,” but not all lead to the economic progress we now need. I call them: industrialist or businessperson (let’s call it Entrepreneur 1.0); Speculate-ship, as I mentioned at the beginning; and Tinkerer—the newest one and the basis for the society of tinkerers. Tinkerer is only now emerging. It longs for entrepreneurship with meaning. It fulfills our ambition for wealth that is sustainable.Luis proposes that tinkerers work on something different:

... an Entrepreneur 1.0 culture that includes today nearly everyone who dares launch a business—a technology company, restaurant, consulting firm, law firm, or whatever—or who evolves a work of art, movie, or book into a business.

The key characteristic these Entrepreneur 1.0 people share is that they are driven to work on something they are curious about, care about doing, or think they are good at. Extreme Entrepreneur 1.0 people are further defined by a problem they have an itch to solve — typically a problem that looks intractable to others.

... Most prevalent in the past few decades has been doing a startup — or more accurately Speculate-ship.

The goal: found a startup born to be sold — and exit before it exits you.

Speculate-ship is fueled by Lean Startup, Design Thinking, the 24 steps of Disciplined Entrepreneurship, and the Startup Owner’s Manual. It’s driven by evocative buzzwords (shown here in italics): have a product or service idea; talk to lots of relevant people to validate it; give the high growth speech; do some inexpensive experimentation about the features of a single would-be product of a single-product startup; and measure success by number of users, not dollars. If it doesn’t work out, start again with a new idea for a new product.

To tackle the problems traditional approaches to venture finance or philanthropy have put out of reach, these new professionals are in need of a community, instruments, a method, and jobs in which to deploy their talents for problem solving. ...

We don’t need more minimally viable products.

We need more maximally viable organizations attacking big problems with a tinkerer’s mindset and a capitalist’s goals.

... I envision a new kind of investment and development firm set on exploring problems that matter, building bold organizations that fail to fail, recycling insights and technologies to arrest the innovation waste, and making instruments for problem-solving broadly available to propel a Society of Tinkerers committed to addressing problems that matter.

I do agree on viable organisations attacking big problems - potentially new institutions growing out of the ones that work - and I do agree these need to be sustainable if at all possible - they can't live on grant money. But I'm not sure it's viable, or sensible, to focus on the wealth generation aspects. I wonder whether Luis has encountered movements like the Zebras. The community and tools are critical to support this new way of doing things.

David Graeber, whose work I came to rather late, died this week. Some highlights of his work are over here.

Originally via David Bent, although it's doing the rounds more now:

|

| https://twitter.com/James_BG/status/1302173118258188291 |