Weeknotes: resilience, urban manufacturing, co-op investment, video calls

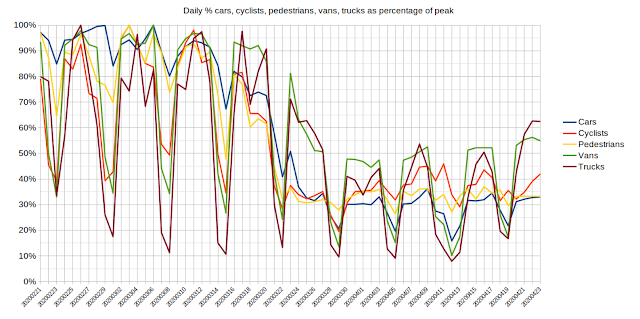

Ian Lewis, who in normal times occupies the office next to mine at the Computer Lab, works on SmartCAMBRIDGE and so has access to fascinating data about how things have changed since early 2020 in the city:

Dave Birch wonders whether this might be an opportunity to build an appropriate digital identity infrastructure. There are four categories of pandemic response digital tool: three from the Economist, and one more:

The Bennett Institute, who do some great thinking, produced some interesting papers in lieu of its planned annual event.

Geoff Mulgan writes about collective intelligence, government and more:

Heather Leson gave me a great selection of guides and tips for looking after volunteer communities responding to crisis. Tips for humanitarian self-care from info4disasters and a super zine by Katie Falkenberg, from 2016, to help humanitarians to look after themselves, were particular highlights.

There are lots of juicy ideas in “A Crowdsourced Sociology of COVID-19” by Jenny L. Davis and many others. (This bitesize selection appears amongst other sociology perspectives on the pandemic.)

Matthew Taylor has written an article about what change might come about - the three conditions that make it most likely that the crisis will have long-term intentional impacts seem fairly obvious:

Janet Gunter shared two great lists of emergency pandemic funding sources - for social enterprise and for charities.

In Vaughn Tan's latest newsletter, there's an exploration of resilience for hospitality businesses:

The main group I've been working with is refocussed on matchmaking and trying to help share information and connections on request, with a more accessible and personal touch (support requests going to a team, rather than forms to populate a database). It feels like this should be useful both for those in need of PPE who want advice or links to possible sources, as well as projects looking to scale up their manufacturing or formalise their processes. We'll see.

Hannah Stewart shared a thread from Cory Doctorow highlighting how networks and sharing have supported pandemic response - "Neoliberalism's imperative to look only at how things work (not how they fail) created lean, overstretched supply chains that allowed investors to extract huge surpluses from companies."

On similar themes, Bill Janeway gave a seminar for the Trust&Technology Initiative about economics and trust. The main takeaway for me was about supply chains; technology has removed frictions, and the pace of business has eroded standby stocks and systems, so previously resilient supply chains have become fragile. Supply chains may become a greater concern for company leadership, with chief risk officers engaging in supply system approvals. However, whilst it may seem obvious that 'just in time' supply chains have caused problems during the pandemic, and that companies should move to 'just in case' supply chains (second sources, holding buffer stock etc), this change may not happen. Doing this, and (re)building capacity for resilience, would hit profits, and we should not believe that enlightened self-interest will be enough for for-profit entities to change how they work - there will need to be external drivers to force this.

A reminder via Rachel Coldicutt that campaigns to change things take a long time - often a decade or more.

"the thing that’s lacking isn’t knowledge, but the courage to exercise it."

Kettle's Yard Open House residency this year takes the form of the campaign for empathy, which is a fascinating idea. There's already some fun conversation menus and more. I'm mostly experiencing this via instagram.

Thanks to Nathan Schneider and Danny Spitzberg for raising the profile of the recent Indie VC investment in Savvy.coop - an unusual/pioneering investment as co-ops do not usually raise venture capital, and traditional models on both sides of the table needed some adjustment to make this work. I think this is really exciting as it demonstrates how scale-up capital can be accessed by user-owned co-operatives who want to operate sustainable, valuable businesses and not just get to an exit. There was a good event (now a video) earlier this week showcasing the deal.

Jennifer Brandel (one of the co-creators of the Zebra movement) writes about organisational shifts:

Admire the exhibits in the Museum of the Fossilized Internet: highlighted delightfully in Michelle Thorne's thread of images.

It's always good to catch up with Chris Adams and be reminded that work continues on other issues such as climate. His activities with ClimateAction.tech and the Green Web Foundation are super illustrations of how different communities can take action today even in areas not obviously related to climate. This week's FT Moral Money looked at localisation which may be in vogue again now that Covid-19 makes local supply chains look better, and has some great figures from Bank of America about potential side effects here on carbon. Rio Tinto's CO2 intensity varies from 2tCO2e/tn in US hydro-powered plant to 17 when coal-fuelled in Australia; “shipping canned tomatoes cross-border has 5 times [the level of] CO2 emissions versus locally farmed and loosely packed”.

Chris has also been thinking about video conferencing solutions with sustainability and open source lenses, as well as privacy (well covered by Mozilla).

On a related note, I'm grateful to Terence Eden (thread) for sketching some ideas about ways video meetings can be better than in person (in response to the various people writing about how exhausting video meetings are - such as this piece). Ultimately people vary and any kind of meeting can have pros and cons, and perhaps exercising some empathy will be helpful. There are all kinds of reasons why one type of meeting will be better than another based on people's health, personal circumstances, personality, mood and more.

Vicki Boylis has been looking at Google Docs and collecting all kinds of uses - payment system, chat platform, file access control, budgets, workflows.

Ultimately though these are collective action challenges, not individual ones, as I've noted here before.

On a related note, is collective.tools what I hoped the Digital Life Collective might be - a user-owned co-operative offering useful digital services?

It was lovely to be reminded via Paul Williams of one of my favourite bits of learning fluid dynamics, back in the day:

|

| https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~ijl20/cambridge_lockdown.html |

The first is documentation: using technology to say where people are, where they have been or what their disease status is. The second is modelling: gathering data which help explain how the disease spreads. The third is contact tracing: identifying people who have had contact with others known to be infected.

... A fourth category... demonstrating that people have the COVID-19 antibodies and are thus no longer susceptible to infection.It's a good outline including some of the social and ethical challenges, but overall recommending:

Dealing with the pandemic has brought issues of security and privacy to the fore and made many of us rethink some of the issues. It is time for serious and informed national debate about building a digital identity infrastructure that will support not only government and business but also society in an interconnected age.

The Bennett Institute, who do some great thinking, produced some interesting papers in lieu of its planned annual event.

Geoff Mulgan writes about collective intelligence, government and more:

This experience convinced me of the practical and theoretical task of better understanding government as a system of cognition, and one that is constantly in a struggle not to be deceived, diverted and deluded.

Apart from everything else that requires better metaphors. Government is often imagined as like the COBRA room – a command centre with a single brain and the Prime Minister at its heart - and there are a few moments when this is true. But a much more accurate picture of government accords with the contemporary view of neuroscience which sees the brain more as a network of sometimes cooperating and often competing modules, constantly jostling for primacy, rather than as a neat pyramid. Within governments multiple different ways of thinking combine and collide. They include the three types of thought that Aristotle described: techne – the practical knowledge on how to build a hospital in a week or distribute emergency loans, which is closest to engineering; episteme – the more analytic knowledge of macroeconomics, or evidence on what works, or the modelling of pandemics, closer to what we call science; and phronesis – the practical wisdom that comes from experience, and hopefully includes an ethical sense and an understanding of contexts.

They also include the kinds of knowledge owned by different professions with government:

The crucial point is that there is no metatheory to tell which you should pay most attention to at which time. Faced by an epidemic it’s wise to lean on your scientists – but they can’t tell you whether it will turn out to be socially acceptable to ban human contact, close the schools or arrest people for leaving exclusion zones, and in most cases the different types of knowledge will point in conflicting directions.

- Statistical knowledge (for example of unemployment rises in the crisis)

- Policy knowledge (for example, on what works in stimulus packages)

- Scientific knowledge (for example, antibody testing)

- Professional knowledge (for example, on treatment options)

- Public opinion (for example quantitative poll data and qualitative data)

- Practitioner views and insights (for example, police experience in handling breaches of the new rules)

- Political knowledge (for example, on when parliament might revolt)

- Economic knowledge (for example, on which sectors are likely to contract most)

- ‘Classic’ intelligence (for example on how global organised crime might be exploiting the crisis)

So any government badly needs the integrative intelligence of phronesis, or wisdom. That means being fluent in many frameworks and models and having the experience and judgement to apply the right ones, or combine them, to fit the context.Geoff concludes:

While business has dramatically shifted so that the best capitalised are the ones founded on data and knowledge – there has been no comparable shift in the public sector. More common is either misplaced faith in the intuitions of a single leader; or variants of the British tradition of the ‘clever chaps’ theory of government, that if only you could put a few smart people in No 10, any problem could be solved. Meanwhile the digital teams in governments are much more focused on the admittedly useful work of applying the lessons of online services in business rather than addressing how government could think more intelligently.

Yet it’s not too hard to describe a more ideal kind of government: one that attends to the various elements of intelligence it needs, from observation to empathy to prediction; one that links them together in intelligence assemblies for all the tasks that matter most; and one that is led by officials and politicians with sufficient integrative skills that they can make sense of complex systems and the messages that come from very different ways of seeing and knowing.Tanya Filer writes (highlights mine)

Palantir holds major Covid-19 response contracts, but it is providing some services without charge, sidestepping the slow proceduralism —and accountability structures —of government technology procurement and contracting. Much has been made of the temporary powers accrued to the state in the current emergency in return for providing us with greater security. But state capacity for crisis management may at least partly now depend upon technology-sector volunteerism.I appreciate her points about digitisation in government too:

There are stand-out exceptions. Under its previous administration, Barcelona adopted a co-created digital identity focused on technological sovereignty and collective decision-making, linking innovation to the values of social and economic justice, solidarity, and gender equality. Singapore, markedly different in approach and political organisation, encourages innovation within pellucid, state-set parameters, premised on the belief that ‘otherwise either the country moves backwards or the private sector takes over the role of the government.’ In both cases, technology providers are not invited to disrupt governance models of their own accord but to implement clearly articulated visions of collective, digital futures that enjoy at least some support from citizens.

In the UK, new models and experiments are materialising. A way forward may be emerging in the current crisis from an unlikely source: the push for a virtual parliament. The idea is to engage technology to maintain friction in the system. A lot will ride on implementation, but this digitalisation is clearly intended to refresh, not upend, the commitment to oversight built into Westminster-style democracies.

Heather Leson gave me a great selection of guides and tips for looking after volunteer communities responding to crisis. Tips for humanitarian self-care from info4disasters and a super zine by Katie Falkenberg, from 2016, to help humanitarians to look after themselves, were particular highlights.

There are lots of juicy ideas in “A Crowdsourced Sociology of COVID-19” by Jenny L. Davis and many others. (This bitesize selection appears amongst other sociology perspectives on the pandemic.)

Matthew Taylor has written an article about what change might come about - the three conditions that make it most likely that the crisis will have long-term intentional impacts seem fairly obvious:

First, where this is a pre-existing demand and capacity for change.Some of the examples are good, along with the reminder that it is not hope that leads to action as much as action that leads to hope.

Second, where the crisis not only strengthens that demand but prefigures alternative mindsets and practices.

And third, where there are political alliances, practical policies and innovations that are ready to be deployed in the period after the crisis when people and systems are more open to change.

Janet Gunter shared two great lists of emergency pandemic funding sources - for social enterprise and for charities.

In Vaughn Tan's latest newsletter, there's an exploration of resilience for hospitality businesses:

Though Covid-19’s ramifications are still unfolding, the pandemic has already highlighted three things that make a business resilient to uncertainty.

- The flexibility to change business model quickly,

- Loyal customers who trust the business even when it switches to a new offering,

- A deep understanding of what customers need and want.

... I have a weakness for small, owner-operated businesses that pursue a particular idea of quality.The RSA's Cities of Making programme has made their final publication - Foundries of the Future (more information; download the book). Cities need manufacturing for 4 reasons:

To be clear, not all small businesses choose to be small or quality-focused. On the contrary, nearly all small businesses are trying to become big but aren’t competent enough to do so—they’re just not very good businesses to start with.

This may be why business schools (and nearly all businesses) seem to have forgotten about the value of pursuing quality for its own sake by staying small. It seems impossible that it can be viable to do so because pursuing profit and growth has become deeply ingrained in the culture of doing business. There is deep suspicion about how businesses that pursue quality over profit can live long, let alone prosper.

Yet, quality-focused customers can almost always find quality-focused businesses—if they care to look. These businesses are the exception not the rule. They often choose to stay small so they can continue to offer quality, and are rewarded with modest but robust economics built on loyal and trusting customers.

Until now, modern business thinking and media has treated these kinds of small, quality-focused businesses mostly as makers of cool stuff—it hasn’t valorised them as good businesses to run. What gets talked up instead is the unicorn startup and the Fortune 500 company.

But the reality is that small, quality-focused businesses don’t just make cool stuff. They also have an enormous competitive advantage in a time of uncertainty and continual change. They are flexible enough to keep changing their offerings to adapt as the business environment changes, they are more likely to have good ideas about what offerings to change to, and their customers trust them enough to buy these new offerings.

1. The need for innovationBusiness innovation is mentioned here alongside product ideas.

Manufacturing sectors have material intelligence and knowledge of production which, when combined with the design, engineering and science communities, can support the development of innovative solutions – such as the development of the folding Brompton bike in London.

2. The need for environmentally sustainable futures

Cities face a host of environmental challenges. As we increasingly need to find ways to reduce carbon emissions, improve biodiversity, ensure cleaner air and lower waste and pollution, manufacturing can offer key capabilities. Skills in repair, maintenance, and the repurposing of materials and resources can unlock circular economy approaches with the aim of lower material footprints and cycling resources within urban areas.

3. The need for a thriving foundational economyLocal production of energy, food, printed materials etc, and manufacturing-related services such as waste management, infrastructure maintenance, are all mentioned, and seem particularly pertinent now we are all more focussed on key workers and essential services.

From printing to tooling to food production, manufacturing provides services and products which are foundational to the economy. These services are crucial to the functioning of other sectors within the city, from finance to healthcare services.

4. The need for inclusive employmentThe book is worth scanning just for the photos showing what modern manufacturing looks like in an urban context.

Finally, the diversity of jobs and skills within the manufacturing sector provides a key route into and through employment for many people and communities within cities.

For example, a cabinet maker buys wood from a local forester and sells furniture to a local boutique. All three will spend their profits at local food markets, visit local hairdressers and doctors, all the latter invest their profits in buying furniture from the cabinet maker. In other words, for every currency unit invested, there is an additional value produced as currency is circulated from business to business or consumer.

There is a noticable difference between the multiplier effect of tradable sectors (such as manufacturing) compared to non-tradable sectors (such as the public sector or restaurants).11 In the US, a study found that each dollar invested in a locally manufac- tured product supported $1.33 in additional output, which was more than twice that of sectors like retail ($0.66) and professional and business services ($0.61).

... Protecting the local economy from external shocks is commonly referred to as raising autarky and fits into a very different concept for the economy than the financially oriented value-added drivers. Local producers may be less efficient compared to importing goods, but they may be necessary to deal with sudden changes in supply networks, to implement new policy (such as climate change adaptation) and also to allow local industries to change or adapt.Urban manufacturing (defined on p23) is a particularly interesting one - and it is this, as much or more than making, that has been playing a role in making PPE in recent weeks. Some of the early small scale projects have now closed, as larger scale production has come online. Other projects are considering what happens next, as initial crowdfunding will be used up and volunteer effort may diminish as and when workplaces start to reopen. The initial rush of new designs seems to be calming now in favour of designs which can go through regulatory approval and be made in larger volumes; also I suspect initial volunteer energy is tailing off.

The main group I've been working with is refocussed on matchmaking and trying to help share information and connections on request, with a more accessible and personal touch (support requests going to a team, rather than forms to populate a database). It feels like this should be useful both for those in need of PPE who want advice or links to possible sources, as well as projects looking to scale up their manufacturing or formalise their processes. We'll see.

Hannah Stewart shared a thread from Cory Doctorow highlighting how networks and sharing have supported pandemic response - "Neoliberalism's imperative to look only at how things work (not how they fail) created lean, overstretched supply chains that allowed investors to extract huge surpluses from companies."

On similar themes, Bill Janeway gave a seminar for the Trust&Technology Initiative about economics and trust. The main takeaway for me was about supply chains; technology has removed frictions, and the pace of business has eroded standby stocks and systems, so previously resilient supply chains have become fragile. Supply chains may become a greater concern for company leadership, with chief risk officers engaging in supply system approvals. However, whilst it may seem obvious that 'just in time' supply chains have caused problems during the pandemic, and that companies should move to 'just in case' supply chains (second sources, holding buffer stock etc), this change may not happen. Doing this, and (re)building capacity for resilience, would hit profits, and we should not believe that enlightened self-interest will be enough for for-profit entities to change how they work - there will need to be external drivers to force this.

A reminder via Rachel Coldicutt that campaigns to change things take a long time - often a decade or more.

"the thing that’s lacking isn’t knowledge, but the courage to exercise it."

|

| https://twitter.com/seanmmcdonald/status/1253289308070567936 |

Kettle's Yard Open House residency this year takes the form of the campaign for empathy, which is a fascinating idea. There's already some fun conversation menus and more. I'm mostly experiencing this via instagram.

Thanks to Nathan Schneider and Danny Spitzberg for raising the profile of the recent Indie VC investment in Savvy.coop - an unusual/pioneering investment as co-ops do not usually raise venture capital, and traditional models on both sides of the table needed some adjustment to make this work. I think this is really exciting as it demonstrates how scale-up capital can be accessed by user-owned co-operatives who want to operate sustainable, valuable businesses and not just get to an exit. There was a good event (now a video) earlier this week showcasing the deal.

Jennifer Brandel (one of the co-creators of the Zebra movement) writes about organisational shifts:

The skill set needed for the post-pandemic economy is rooted in deep listening, public-powered processes, and mobilizing networks. We’re being called on to dust off, or to learn these skills anew.I particularly like the idea of new metrics for resilience:

... So how do we shift these institutions from churning out information to instead supporting informed and coordinated communities in designing and strengthening the public interest, when the public interest has shifted overwhelmingly to survival, fellowship, mutual aid, shared ownership, community, transparency, and public-powered processes?

...One of the most critical investments is in teaching listening techniques to the people who are in position to help. It sounds obvious, but time and again when we ask our clients, “What process do you have for listening to the people you serve?” and “How does what you hear inform your strategy and execution?” the answer is most often, sheepishly, “We don’t.”

Digging deeper, it always comes down to lacking time, resources and the know-how to listen. Which makes it no surprise when there’s no follow-through on implementing listening processes that can surface insights from stakeholders to decision-makers. Now is the time to finally make that investment.

In order for technology to truly be useful, first people need to get the mentality and techniques down.

... Now more than ever, institutions have the opportunity, and a mandate from the public and their stakeholders to operationalize listening and create feedback loops and systems so they can hear, respond to, and co-create with their community. That means creating clear ways, driven by teams trained in these techniques, and leveraging technology, to hear a community’s call and, with them, organize a coordinated, agile response.

As organizations look to adjust “what success looks like now” and funders look to invest in community response approaches, here are some useful questions to ask. Rather than measure the input of the information, this framework captures community capacity building and the formation of new foundations:

Who was heard, and how often? Occasional focus groups and stakeholder surveys are no longer enough. How will the organization develop a deep, defensible and continual dataset of ever-evolving needs to substantiate the response?

Who designed and deployed the response? How are those who are heard being elevated to designers, decision makers, and those who deploy the strategy? Are they given power beyond providing feedback? How does that increased capacity help strengthen your organization?

Who was helped? How were direct needs served through this new model of deep listening and mutual aid? What new ways of helping were discovered in the process of this experiment? How can that mutual aid be sustainably scaled?

What new techniques and technologies were adopted? How did a team increase their capabilities and capacity to serve? What new techniques and technologies were used? This could be anything from using a simple Google form for the first time to scaling up to bespoke team-training or enterprise software. How has the institution made strides in instilling a culture of continual learning and education to better serve the evolving needs of its members?

Admire the exhibits in the Museum of the Fossilized Internet: highlighted delightfully in Michelle Thorne's thread of images.

It's always good to catch up with Chris Adams and be reminded that work continues on other issues such as climate. His activities with ClimateAction.tech and the Green Web Foundation are super illustrations of how different communities can take action today even in areas not obviously related to climate. This week's FT Moral Money looked at localisation which may be in vogue again now that Covid-19 makes local supply chains look better, and has some great figures from Bank of America about potential side effects here on carbon. Rio Tinto's CO2 intensity varies from 2tCO2e/tn in US hydro-powered plant to 17 when coal-fuelled in Australia; “shipping canned tomatoes cross-border has 5 times [the level of] CO2 emissions versus locally farmed and loosely packed”.

Chris has also been thinking about video conferencing solutions with sustainability and open source lenses, as well as privacy (well covered by Mozilla).

On a related note, I'm grateful to Terence Eden (thread) for sketching some ideas about ways video meetings can be better than in person (in response to the various people writing about how exhausting video meetings are - such as this piece). Ultimately people vary and any kind of meeting can have pros and cons, and perhaps exercising some empathy will be helpful. There are all kinds of reasons why one type of meeting will be better than another based on people's health, personal circumstances, personality, mood and more.

Vicki Boylis has been looking at Google Docs and collecting all kinds of uses - payment system, chat platform, file access control, budgets, workflows.

But I haven’t seen much press at all about how much of a problem it is that a company has not only managed to embed itself into our consciousness with search, but now also lives inside our companies as a complete production system that people rely on to track revenue, run databases, manage vendors, and, yes, distribute billions of dollars.A superb article from Tactical Tech on the difficulty of choosing technologies to use day to day.

I’m not saying that all of this is going to come crashing down, mostly because many of thse systems operate through security by obscurity, but maybe we (and Jack) should back our stuff up at least every once in a while, and maybe take some of these docs out of production.

In this time of crisis we are at a technology crossroads. We are facing trade-offs between what seems efficient and quick versus what seems ethical and safe. In either case, we have to deal with the long-term political and social consequences — giving up on our values or investing in equitable tech.If you have time to grow your own, the article goes on to list a range of tools and a framework for evaluation, which I broadly agree with, although I might replace "trusted (audit)" with "trustworthy (audit, governance)". It's one of the most helpful such lists I've come across.

...

we are often asked for alternatives to the most commonly used tools. Many people ask us to recommend communication, collaboration and networking tools that are designed with users’ rights and privacy principles as their primary design choice – and that work without the big data-hoarding complexes of Facebook, Alphabet or the like.

These questions have become much more frequent during the current coronavirus pandemic. The expectation is that we, or other entities working with technology and society, will recommend the ultimate infallible toolbox of ready-to-use tools. People want the list of tools they should install and they might not want to work through the questions about why to use them or why not, which are in truth difficult. There is an urgency to the situation and people are concerned about the choices they make, so we often end up suggesting some easy-to-use alternatives that demand less investment in skills, resources and time. But it’s not – and shouldn’t be – that simple.

... The idea that there are tools that would always work for everyone, everywhere; require no extra knowledge and zero additional infrastructure; are fair and just, and protect users at all times, is a dream that has not yet come true.

... These two models describe the situation we are in: either we have to eat fast food or grow our own. The former is convenient but not very healthy; the latter is better for us but is time and skill intensive.

Ultimately though these are collective action challenges, not individual ones, as I've noted here before.

On a related note, is collective.tools what I hoped the Digital Life Collective might be - a user-owned co-operative offering useful digital services?

It was lovely to be reminded via Paul Williams of one of my favourite bits of learning fluid dynamics, back in the day:

|

| https://twitter.com/eddedmondson/status/1252970817291538434 |