Monthnotes: Feminine power, disruption, hope and care

It's been too long, and so these notes are too long, but my excuse is that I was wrapping up at lowRISC.

On feminine power:

Onto technology stuff.

Benedict Evans's 2020 Davos deck on the state of tech manages to present a nice balanced overview.

How can you have confidence in third party code? I particularly like the data on Stack Overflow here. As well as code snippets with bad security, there's good advice to be found. Sadly a lot of the code reused in Android apps is problematic.

Martin Weller writes about disruption:

Let's make disruption a dirty word again. (Who said this recently?)

Invention vs innovation - a perspective from Clare Reddington at Watershed:

The evolving use and design of household spaces, via Kneeling Bus:

A call for low-tech, 'dumb' cities which are greener than smart ones. Whatever smart might mean, of course.

Shared by quite a few people I follow on Twitter: depressing GDPR point:

(You too can support enforcement in Europe by becoming a member of noyb, which brings privacy cases.)

Via Patrick Tanguay, some hope at the end of this article about the "toxic hellscape" of the internet:

And so to climate.

Also via Patrick Tanguay, Anne Galloway writes about designing for more than just humans:

Alex Steffen tweets (check the thread) that the climate emergency is an era, not a crisis.

The NHS is working out how to get to net zero carbon emissions.

Via Noel Sharkey, a Wired article on the energy consumption of AI (well, machine learning), some of the scary headlines, plus the efforts to improve energy efficiency and raise awareness of this in research and developer communities.

An intriguing but long article from Don Goodman-Wilson about the various ways open source is broken. I also came across this list of challenges with open source.

A very timely - for me! - and excellent review of the state of open source licensing, thanks to TideLift. Starting with some thoughts on the ethical licences movement:

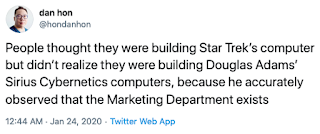

Via Dan Hon -

Can good work improve UK productivity? A great summary from Matthew Taylor of a new set of essays. Tackling bad work is one of the recommendations - I wonder if this includes the bullshit white collar jobs from Graeber's talk [last notes post].

The two-part David Runciman / Azeem Azhar podcast on the future of technology, intelligence and politics was fascinating (Talking Politics / Exponential View). I was particularly struck by David's thinking about the generation gap, and the power landscape of states and corporations.

I finished Clarke's Tipping Point, feeling a new appreciation for national security matters. Now there's this:

Haydn Belfield tweets about the Doomsday Clock, now at its closest ever to midnight (doom). Haydn is at the Centre for Existential Risk at Cambridge so is something of an authority on these things.

Making your living online can be quite risky. This tale of a fairly tech savvy mid-scale YouTuber getting hacked shows you how quickly reputation and content can be lost, and how hard it is to regain.

Via Bruce Schneier, tree code.

Cat and Girl speak the truth, as ever:

On feminine power:

But the more I acted the Strong Female Lead, the more I became aware of the narrow specificity of the characters’ strengths — physical prowess, linear ambition, focused rationality. Masculine modalities of power.That article came via Cassie Robinson, who writes separately about her new job. What I love most about her post is her description of leadership:

....

It’s difficult for us to imagine femininity itself — empathy, vulnerability, listening — as strong. When I look at the world our stories have helped us envision and then erect, these are the very qualities that have been vanquished in favor of an overwrought masculinity.

...

I don’t believe the feminine is sublime and the masculine is horrifying. I believe both are valuable, essential, powerful. But we have maligned one, venerated the other, and fallen into exaggerated performances of both that cause harm to all. How do we restore balance? Or how do we evolve beyond the limitations that binaries like feminine/masculine present in the first place?

...the things I really believe good leadership entails — authenticity, allyship, developing and championing people’s strengths, providing clarity and a strategic vision, valuing everyone’s voice and contribution, being a buffer and having people’s backs, removing arbitrary hierarchy, and paying care and attention to people.

Onto technology stuff.

|

| https://twitter.com/hondanhon/status/1220507599386243072 |

How can you have confidence in third party code? I particularly like the data on Stack Overflow here. As well as code snippets with bad security, there's good advice to be found. Sadly a lot of the code reused in Android apps is problematic.

Martin Weller writes about disruption:

I think to give it fair credit, the initial idea of disruptive innovation was both powerful and useful. Coming as the digital revolution really began to impact upon every sector of our lives, people were looking for theories to explain the new logic of these businesses that seemed to arise from nowhere and achieve global domination overnight. How could Kodak disappear? Why did Microsoft become bigger than IBM? The concept of sustaining and disruptive technologies offered a means of explaining what was happening. ...Martin goes on to detail a variety of reasons why disruption has become a problematic idea.

But some time around the web 2.0 boom, disruption shifted from being one possible explanatory theory to a predictive model, and then to a desirable business plan. These are very different things and they carry with them different responsibilities. Every start-up wanted to ‘disrupt’ an existing business. It shaped Silicon Valley thinking more than any other theory, and in 2020, I think we can review that and say it was almost entirely harmful in our relationship with technology.

Let's make disruption a dirty word again. (Who said this recently?)

Invention vs innovation - a perspective from Clare Reddington at Watershed:

That doesn’t mean we don’t do unusual, brave, audacious things – it just means we are often making them harder to spot, to cherish and to nurture BECAUSE of our metrics. We pin bright ideas down before they can fly. In an attempt to understand and plan for the uncertain times we live in, we CLAIM certainty where it doesn’t belong, and I believe this is partly because we are confusing innovation and invention:

Invention is magic. It is the spark of an idea, it is a new way of doing something, it is the unknown.

Invention thrives in non commoditised conditions of trust, inclusivity, joyfulness and care.

It is revealed over time and is hard to predict.

Innovation is how we grow that idea, the systems needed to make it scale-able, replicable, stable. Its systems are easier codified and its impact is easier modelled.

When we use the measures of innovation to pin down invention, we get caught in the certainty trap and stifle the new ideas and new talent we desperately need. I am not anti reporting, or being repsonsible with public funding or even counting impact - but if we define our outputs before we begin and then constantly reference them in meetings, perhaps we will only achieve exactly what we have predicted.

How then can we programme in both – embrace the uncertainty and magic of invention and the potential for impact of innovation?

If we concentrate on spaces, tools, dreams and behaviors alongside money and measures, perhaps we will get what we actually need.

The evolving use and design of household spaces, via Kneeling Bus:

Last week, Taylor Lorenz wrote about the explosion of videos filmed in the bathroom on TikTok. “Videos shot in the bathroom consistently outperform those shot elsewhere, many creators say,” because bathrooms have mirrors, good lighting, and favorable acoustics, among other qualities. People have been performing in front of their bathrooms long before that was “content”—before there was a platform for sharing it with the world—but TikTok has finally turned the bathroom inside out, transforming that most private and solitary domestic enclave into a public stage, the most important room in the Hype House. A week before that piece, John Herrman similarly analyzed Ring, describing how the Amazon doorbell cameras have turned the suburban front porch into another kind of stage where the creepy and the whimsical commingle. Paired with Lorenz’s piece, Ring seems like TikTok’s evil twin, and together the platforms repurpose two traditionally mundane and functional parts of the house that have suddenly become symbolic loci in a despatialized internet galaxy.English housing developments could do better at design - here's a recent audit. The points around shared outdoor space seem very pertinent, given recent developments I've seen.

...

if the bathroom is the most porous and connected room in the house, at least for now—the foyer where you welcome your online friends to come inside—then the physical entryways are being correspondingly fortified and we won’t even answer the door. Herrman describes Ring footage in which a neighbor knocks on a door, locked out of her house and freezing: Instead of being invited inside or even encountering another human, an unseen entity simply summons the police. The porch is bigger than it needs to be while the bathroom is too small.

A call for low-tech, 'dumb' cities which are greener than smart ones. Whatever smart might mean, of course.

Shared by quite a few people I follow on Twitter: depressing GDPR point:

|

| https://twitter.com/airavn/status/1219948751428771843 |

Via Patrick Tanguay, some hope at the end of this article about the "toxic hellscape" of the internet:

The same things that give me panic, that quite literally lay me out, also give me hope. They’re the same things that inspire me to open my eyes, stand up, and tell nihilism to go fuck itself. […]We need to keep hold of hope.

If everything we believe about journalism is true, then why has none of it been working? The healthy response to this question is anxiety; paradigms hurt when they shift. […]

The kind of anxiety I’m describing is the north star guiding ships onward. At least it can be, when the worry itself is reframed and harnessed toward the common good. Because what is it, other than an awareness of consequence and connection? What is it, other than the recognition that things should be different? There is no yearning for a better world when there are no guiding stars. They are a necessary precondition for meaningful change.

|

| https://twitter.com/volansjohn/status/1220753096281817088 |

Also via Patrick Tanguay, Anne Galloway writes about designing for more than just humans:

Agriculture is also one of humanity’s most heavily designed activities, which should remind us that it can be re-designed, and needs to be re-designed when it stops working for all of us.These very different ways of thinking and being are so surprising when you are used to Western/Northern business and technology processes and ideas.

But I’m not a believer that technology under capitalism will be the planet’s salvation, and I tend to part ways with (commercial?) designers and technologists who aim to design more “precision” agriculture through “intelligent” machines, and I’m constantly watching for bad omens. The ethos of the More-Than-Human Lab draws on Donna Haraway’s “staying with the trouble” and tries to go beyond the design of human-nonhuman interactions to reimagine human-nonhuman relations. For me, this means not trying to “fix” the world, and resisting both purity and progress to live well together through uncertain and difficult circumstances.

The deep irony (?!) is that indigenous cultures all around the world and many non-Western religions have always understood that nature and culture aren’t separate, and that humans aren’t superior in our abilities or experiences. Western intellectual history and industrial capitalist societies have not allowed this kind of thinking to take hold except for amongst a fringe few, and I think this has played a pivotal role in the current climate crisis and the impoverished range of corrective measures on offer.

Alex Steffen tweets (check the thread) that the climate emergency is an era, not a crisis.

The NHS is working out how to get to net zero carbon emissions.

Via Noel Sharkey, a Wired article on the energy consumption of AI (well, machine learning), some of the scary headlines, plus the efforts to improve energy efficiency and raise awareness of this in research and developer communities.

An intriguing but long article from Don Goodman-Wilson about the various ways open source is broken. I also came across this list of challenges with open source.

A very timely - for me! - and excellent review of the state of open source licensing, thanks to TideLift. Starting with some thoughts on the ethical licences movement:

Other licenses have taken up this torch as well. During the year, the OSI saw requests for comments on the Working Class License and a license “respecting European values” like privacy, both of which are roughly what they sound like on the label. There is also now an anti-carbon license, and I’m sure others I have not yet seen. We should expect to see more of the same in 2020.

....

Inevitably, as open source has “won,” money has become ever more central to how it functions. It turns out it is hard to sustain the entire software industry on a part time basis! Licensing has not played a central role in this discussion, but 2019 gave several examples of how licensing and money are entangled.

....

Open source has, in many important ways, won. Virtually everyone who writes software uses it. But that also means that everyone who writes software has a stake in what open source is and can mean.

In a politically charged moment (spanning the gamut from Chinese labor to global carbon extraction to Silicon Valley VC), that growth in open source is inevitably going to lead to contestation of what the term should mean—and what our licenses should do. So expect more of the same in the year to come, as we continue to argue about what our legal tools can and should do.

Via Dan Hon -

via Tim Maughan, Sara Yasin’s tweet about a grocery store throwing a 1st birthday party for a security robot, and Adrian Short’s cutting question about whether the store ever holds a birthday party for the actual security guard.Oxfam launched their Time To Care report, describing care labour around the world:

Economic inequality is out of control. In 2019, the world’s billionaires, only 2,153 people, had more wealth than 4.6 billion people. The richest 22 men in the world own more wealth than all the women in Africa. These extremes of wealth exist alongside great poverty. New World Bank estimates show that almost half of the world’s population live on less than $5.50 a day, and the rate of poverty reduction has halved since 2013.

This great divide is based on a flawed and sexist economic system. This broken economic model has accumulated vast wealth and power into the hands of a rich few, in part by exploiting the labour of women and girls, and systematically violating their rights.

At the top of the global economy a small elite are unimaginably rich. Their wealth grows exponentially over time, with little effort and regardless of whether they add value to society.

Meanwhile, at the bottom of the economy, women and girls, especially women and girls living in poverty and from marginalized groups, are putting in 12.5 billion hours every day of care work for free, and countless more for poverty wages. Their work is essential to our communities.

It underpins thriving families and a healthy and productive workforce. Oxfam has calculated that this work adds value to the economy of at least $10.8 trillion. This figure, while huge, is an underestimate, and the true figure is far higher. Yet most of the financial benefits accrue to the richest, the majority of whom are men. This unjust system exploits and marginalizes the poorest women and girls, while increasing the wealth and power of a rich elite.

This is not just an issue for poor people elsewhere. In the UK, the Centre for Aging Better says (emphasis mine):

Around 7.6 million people work as unpaid carers for a family member or friend. Around a quarter of people aged 45-64 are carers, and even that’s an underestimate.A fascinating history of the big firms of management consultancy in the Atlantic, via Steve Song. The focus here is how companies previously able to promote from within, resulting in a good proportion of managers who knew life on the shopfloor (or equivalent), instead cut their management, and removed links and mobility throughout the layers of staff. The result is more powerful executive elites with exceptional pay. Perhaps also more bullshit jobs, as what management remains has reduced skills or abilities to wield them.

...

The Care Act 2014 was revolutionary in introducing new rights for carers in England, including a focus on promoting wellbeing, a right to a carers’ assessment based on appearance of need, and a formal right for those needs to be met. But carers still face serious inequalities in accessing essential services, maintaining social connections and enjoying the support network these things provide.

It’s crucial that local authorities take account of the results of carers’ assessments and deliver on support where it’s needed, both on an individual and a systemic basis.

Can good work improve UK productivity? A great summary from Matthew Taylor of a new set of essays. Tackling bad work is one of the recommendations - I wonder if this includes the bullshit white collar jobs from Graeber's talk [last notes post].

The two-part David Runciman / Azeem Azhar podcast on the future of technology, intelligence and politics was fascinating (Talking Politics / Exponential View). I was particularly struck by David's thinking about the generation gap, and the power landscape of states and corporations.

I finished Clarke's Tipping Point, feeling a new appreciation for national security matters. Now there's this:

|

| https://twitter.com/STS_News/status/1219352003320647682 |

Hmm.

Making your living online can be quite risky. This tale of a fairly tech savvy mid-scale YouTuber getting hacked shows you how quickly reputation and content can be lost, and how hard it is to regain.

Via Bruce Schneier, tree code.

Cat and Girl speak the truth, as ever:

|

| http://catandgirl.com/up-and-up/ |