Weeknotes: mundane technology, commons based peer production, communities of co-operative practice

A great analysis from Apache, of the Apache open source way to reach sustainable open source success - breaking down the mission statement and looking at each piece in depth. A really important and useful clarifying piece, which also highlights how much it matters to be clear about what you are doing, for which community.

It's from 2007, and it's fascinating to see what is there, and what is not; and what made sense in terms of cardinals (real life vs web; practical vs intellectual). Wikipedia is a rare example of an interlinked system; most other parts are islands. That perhaps makes sense for IRC, say, but at least you knew there were islands with IRC. There were atlases, in the form of directories. I couldn't say what Slacks, Telegrams or Whatsapp groups there are now.

The 2010 version is quite different.

I was very taken with this piece which was mentioned in Patrick Tanguay's Sentiers 72 where it is introduced as: ... [Amber Case's] vision for a middle futurism. Imagined between shiny perfect forecasting videos, and demoralizing and not very useful dystopias. A middle future is: maintainable, transparent, “allows for both chronos (structured) and kairos (in the moment) time,” allows for empathy, and works for the long term.

My experience of working at AT&T Labs at the turn of the century (or, the peak/fall of the dotcom boom, depending how you look at it) means I feel a particular kinship with PARC. We too worked on very different kinds of technology system concept, which have mostly not been realised since. Amber writes:

Following on from last week's democratising the knowledge economy, this week sees the launch of a new book by Michel Bauwens, Vasilis Kostakis and Alex Pazaitis - "Peer to peer: the commons Manifesto." As a manifesto, you can grab the PDF from their site, and it has useful and accessible content; I confess I skimmed the more in-depth economics detail though.

The diagrams on p9-10 are helpful explanations of commons and peer to peer concepts. p15-19 talk about what entrepreneurship means in this context, and what this looks like within a commons/P2P ecosystem; this segues into case studies of some less well known commons ecosystems (eg Enspiral, Farm Hack). Later on, the book explores today's internet status quo of "cognitive capitalism" and some alternatives. Whilst I think "surveillance capitalism" is a great term, which captures the imagination with association with negative ideas, "cognitive capitalism" considers the extraction of value from our individual and collective thinking, creation and attention:

p39 onwards looks critically at localisation, and options for local, global and federated commons. p44 looks at production and "design global, manufacture local," very much the essence of what we did at Field Ready, along with other (referenced) projects such as OpenBionics, RepRap etc. I am not sure what perspective my experience of the challenges of making this vision actually work at a useful scale (anything greater than a single hyperlocal project) offers, other than that it's easy to have an engaging "TED talk" on this stuff, much harder to make it work in practice for all kinds of reasons. (It may be argued that by developing such a transformative and genuinely disruptive vision in the most brutally tough context of humanitarian aid we were making life unnecessarily hard for ourselves at Field Ready; on the other hand, the clear need for change and better solutions meant the drivers were more evident than in other, more stable situations.)

p55 gets to the heart of the thing - a commons transition strategy, built on ideas of:

I like this focus on building entrepreneurial communities and institutions, which I'm reading about after a week of talking and thinking about entrepreneurial support for co-operatives. This has been motivated by several things - talking with UnFound who are supporting platform entrepreneurs in the UK, catching up with Graham Mitchell of Platform6, and hanging out on the CoTech forum (if you don't know it, check out this recent thread which covers projects in Preston and Kirklees, community networks and more). I've also been thinking about whether I should put in a Mozilla Fellowship application this year, and if so what for. (Thanks to encouragement from lovely Mozilla staffers, following on from my grant from Mozilla last year, I've been pondering what form a fellowship might take. The initial application is extremely concise - feedback welcome, especially on how to shape a useful project which could be undertaken in a role as a practitioner, working on collaborative engineering and open IP, and therefore an active member of the community of practice at the same time.)

I'm not a hardcore co-operative person, and I think there's potential for other not-formally-co-ops to offer similar wins for the commons and for collective benefit. But all of these forms require business models and governance/incorporation structure that are not 'normal' for tech startups today. So much of our tech entrepreneurship narrative, support structures and resources (money, mentoring, training) are geared towards a very specific form of tech venture - one which takes investment capital motivated by growth and high returns. Supposedly this is also high risk, although the risk is often in marketing rather than technical risks.

How many potential or early stage entrepreneurs are aware there is an alternative path? If you are lucky you get to hear about social enterprises, which are still for-profit based on a similar investment (and generally exit) path, but with a mission stuck on the side. (I am exaggerating slightly here - there are many good social enterprises who have a depth of mission greater than profit+purpose - but the general tenor of a lot of enterprise support programmes is clear. You are basically following the same path - funding rounds, growth, exit, plus you may be working in a 'for good' market like health or education, or you may have some social benefit embedded perhaps giving a percentage of profits to a good cause.) And even if you know it's a possibility, you probably don't know how to go about it. You need resources (which do exist, somewhat, although they could be better signposted), and, as starting and growing a new venture is actually hard, you also need help - mentors, peers to encourage you along the way, and so on. Finding these is non-trivial, today, although networks such as the Zebra community help. There's no one specific business model or governance structure that is right; many challenges will be shared by co-ops, non-profits, hybrid enterprise structures, collaborative projects and commons initiatives - figuring out strategy, finding talent, securing resources. Whilst each of the specific communities may be starting out small it's especially important to nurture the fabric they exist within, making sure entrepreneurs can find the right support, even if it's not in the most relevant community. Networks and resources need porous edges so that frictions are minimised, and the overall movement can get started.

It feels like there is valuable work to be done:

There's some other good thoughts on platform co-ops, the need for replication rather than scaling, and the capital challenges for them, in a follow up to Nesta's event from Leo Sammallahti. Leo also identifies a need for "lighthouse" institutions to help with, in essence, marketing new platform co-ops.

If you are reading this soon after I write it, consider writing to your MEPs if you have them, and push back on Article 13 (content upload filters) and Article 11 (link tax).

More information on https://saveyourinternet.eu/act/ or https://action.openrightsgroup.org/our-last-chance-stop-article-13

Deb Chachra is also writing a book, and in the meantime has written a lovely twitter thread with inspirations about infrastructure and maintenance. Recommended.

A great article on end user programming, which can empower users by giving them more control over their tools (HT Martin Kleppmann), with some super insight into how to go about this practically (although it is very hard).

Richard Pope and James Darling reflect on ten years from the first ‘National Hack The Government Day’. I wasn't there in 2009 although many friends were. The diverse communities ( sharing, learning and challenging each other across boundaries) of those early efforts have evolved since, with many people moving into, and out of, key institutions.

I marched on Saturday with thoughts of revoking Article 50, taking some time to listen, reconnect and build bridges - within the UK as well as with Europe. The FT has a great piece tearing into a lot of the Brexit lines [paywall]; the New York Times has a piece about the nostalgia myths which got us here, on both sides.

I was struck mostly by the diversity of views and desires expressed on the march. A demand for a "people's vote" was, of course, well represented as a they had organised the day, but there were also main straightforward "remain" placards and banners, and quite a few "revoke Article 50" signs. Frustration with Theresa May, optionally the cabinet as a whole, or the Conservative Party, alongside frustration with Labour. I was also surprised by the number of local groups and communities who were marching together - towns and counties from around the UK, "votes for goths", scientists for EU, and so on. And the dogs - a lot of dogs against Brexit, broadly speaking.

Also in Sentiers this week, a link to this Vox piece on fashion in air pollution masks, as they become more prevalent in Western cities as well as Asia. After a day marching in London I was sneezing - which may be unrelated of course. I didn't spot any masks on the protesters - probably wise protest practice, although interesting given how many cyclists and others one usually sees in masks in London now.

The mission of the Apache Software Foundation (ASF) is to provide software for the public good. ....Investopedia defines a public good as "a product that one individual can consume without reducing its availability to another individual, and from which no one is excluded." On the surface, this is a good definition for our use of the term. However, there is a nuance in our use. Our mission is not to produce "public goods" but to "provide software for the public good".A lovely article from Ingrid Burrington on how the internet acquires the trappings of the nation state, with borders and mapping, and also on mapping the internet.

But perhaps the more familiar nation-state accouterment applied to the internet is the rebellious manifesto. The most literal and famous of these is J.P. Barlow's 1996 "Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace," which borrowed the rhetoric of Jeffersonian outrage to situate the net as beyond the purview of governments. If the network-as-nation had a fundamental character in the early days of the internet, it was an outlaw one—where Barlow and the cowboys of cyberspace could declare independence from the dunces of Davos, a Wild West conveniently lacking in genocidal baggage from the last time Americans attempted to manifest their destiny (though still infused with Orientalist aesthetics in cyberpunk culture). This Wild West was only stealing control away from fuddy-duddy benevolent technocrats, the federally funded squares who laid the foundation but lacked the cowboy's imagination.(Highlight mine. I was amused by this cultural take on the investment and development landscape of the early internet, and how it contrasts to now.)

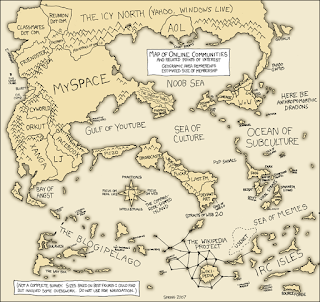

There is some irony to the mapping impulse of platform companies, insofar as they largely emerge from landscapes historically willfully in denial of their own spatial confines. As a place in public imagination, Silicon Valley is more often defined by its companies than its geography. This, in part, might be ascribed to the particular way most tech companies inhabit these suburban cities on the San Francisco Bay Peninsula: on campuses, enclaves set apart from the day-to-day of the cities they inhabit. To claim that Facebook has "offices" in Menlo Park doesn't really do justice to the experience of driving along its particular expanse of the Bayfront Expressway where its formerly-Sun Microsystems compound and its Frank Gehry-designed expansion loom in the distance.When I think of mapping the internet, I think of the poster which for a long time hung in the kitchen at Makespace - XKCD's map of online communities.

It's from 2007, and it's fascinating to see what is there, and what is not; and what made sense in terms of cardinals (real life vs web; practical vs intellectual). Wikipedia is a rare example of an interlinked system; most other parts are islands. That perhaps makes sense for IRC, say, but at least you knew there were islands with IRC. There were atlases, in the form of directories. I couldn't say what Slacks, Telegrams or Whatsapp groups there are now.

The 2010 version is quite different.

I was very taken with this piece which was mentioned in Patrick Tanguay's Sentiers 72 where it is introduced as: ... [Amber Case's] vision for a middle futurism. Imagined between shiny perfect forecasting videos, and demoralizing and not very useful dystopias. A middle future is: maintainable, transparent, “allows for both chronos (structured) and kairos (in the moment) time,” allows for empathy, and works for the long term.

My experience of working at AT&T Labs at the turn of the century (or, the peak/fall of the dotcom boom, depending how you look at it) means I feel a particular kinship with PARC. We too worked on very different kinds of technology system concept, which have mostly not been realised since. Amber writes:

Middle Futurism, by contrast, revives the PARC vision, describing a technological path that “takes into account the natural human environment”.I love the idea of mundane futures, where technology is integrated into the world, everyday. And the five principles are great - especially the first, of course!

- A middle future is maintainable. Not just by the company that built it, but by the individuals who use it. There should be a sense of personal pride in being able to fix a system, and a long term job associated with it.

- A middle future is transparent. When the processes going on behind the scenes are invisible, we experience a Kafka-esque reality. If a computer’s “AI” is coming to the wrong conclusions, we should know, and be able to help fix it.

- A middle future allows for both chronos (structured) and kairos (in the moment) time, with a focus on optimizing for human time, not machine time.

- A middle future allows for empathy. It optimizes the best of tech and the best of humans.

- A middle future works for the long term — when an organization adopts a new technology, it should be robust enough to last decades, not just the next OS update.

Following on from last week's democratising the knowledge economy, this week sees the launch of a new book by Michel Bauwens, Vasilis Kostakis and Alex Pazaitis - "Peer to peer: the commons Manifesto." As a manifesto, you can grab the PDF from their site, and it has useful and accessible content; I confess I skimmed the more in-depth economics detail though.

The diagrams on p9-10 are helpful explanations of commons and peer to peer concepts. p15-19 talk about what entrepreneurship means in this context, and what this looks like within a commons/P2P ecosystem; this segues into case studies of some less well known commons ecosystems (eg Enspiral, Farm Hack). Later on, the book explores today's internet status quo of "cognitive capitalism" and some alternatives. Whilst I think "surveillance capitalism" is a great term, which captures the imagination with association with negative ideas, "cognitive capitalism" considers the extraction of value from our individual and collective thinking, creation and attention:

This new form of capital directly exploits networked social cooperation that often consists of unpaid activities that can be captured and financialized by proprietary ‘network’ platforms. It sustains itself from the positive externalities created through human cooperation and the commons.So it feels like a useful term we should use more.

p39 onwards looks critically at localisation, and options for local, global and federated commons. p44 looks at production and "design global, manufacture local," very much the essence of what we did at Field Ready, along with other (referenced) projects such as OpenBionics, RepRap etc. I am not sure what perspective my experience of the challenges of making this vision actually work at a useful scale (anything greater than a single hyperlocal project) offers, other than that it's easy to have an engaging "TED talk" on this stuff, much harder to make it work in practice for all kinds of reasons. (It may be argued that by developing such a transformative and genuinely disruptive vision in the most brutally tough context of humanitarian aid we were making life unnecessarily hard for ourselves at Field Ready; on the other hand, the clear need for change and better solutions meant the drivers were more evident than in other, more stable situations.)

p55 gets to the heart of the thing - a commons transition strategy, built on ideas of:

- pooling resources wherever possible

- introducing reciprocity into relationships

- from "redistribution to predistribution" exploring the dynamics between the book's vision of productive communities; coalitions of entrepreneurs; and the for-benefit ‘management’ or ‘governance’ institution; and considers how these fit in local urban commons in particular

- subordinating the capitalist market with better, reciprocal links between the commons and the market, perhaps facilitated by 'copyfair' licences

- Organising at the local and global level

...platform cooperatives have been proposed as alternatives to exploitative sharing economy models. They offer a radical redesign of the ownership and control of online platforms, promoting democratic governance, solidarity and social benefit (Scholz and Schneider, 2016). Platform cooperatives create an enabling environment for employees, customers, and users of digital services and contribute positively to the commons. However, platform cooperatives still pose isolated alternatives designed to counter old forms of capitalism, prone to the frailties of traditional cooperatives.The book ends with the call to action, proposing that:

Open cooperatives aim to expand and interconnect to aggregate, support and protect collective knowledge, tools, and infrastructures. They produce locally but organize around global concerns to build a counter-economy that can deem CBPP to be a full and autonomous mode of production. They seek to create new types of vehicles, through which self-organized workers can realize surplus value and emancipate themselves from the confines of the dominant system.

• Commoners mutualize digital (e.g. knowledge commons, software, and design) and even physical resources (e.g. shared manufacturing machines). We need pooling wherever it is possible.and thus

• Commoners establish their economic entities and create livelihoods for productive communities. We need open cooperatives.

• These economic entities use commons-based reciprocity licensing to protect against value capture by capitalist enterprises. We need copyfair.

• Open cooperatives are organized in participatory business ecosystems that generate incomes for their communities. We need commons-oriented entrepreneurial coalitions.

• The creation of local institutions that give voice to commons-oriented enterprises that build commons and create livelihoods for commoners. We need Chambers of the Commons.p71-73 summarise these in nice diagrams.

• The creation of local or affinity-based associations of citizens and commoners, bringing together all those who contribute, maintain or are interested in common goods, material or immaterial. We need Assemblies of the Commons.

•The creation of a global association that connects the already existing commons-oriented enterprises, so that they can learn from each other and develop a collective voice. We need Commons-oriented Entrepreneurial Associations.

•The creation of global and local coalitions between political parties (e.g. Pirate Parties, Greens, New Left) in which the commons is the binding element. We need a Common(s) Discussion Agenda.

I like this focus on building entrepreneurial communities and institutions, which I'm reading about after a week of talking and thinking about entrepreneurial support for co-operatives. This has been motivated by several things - talking with UnFound who are supporting platform entrepreneurs in the UK, catching up with Graham Mitchell of Platform6, and hanging out on the CoTech forum (if you don't know it, check out this recent thread which covers projects in Preston and Kirklees, community networks and more). I've also been thinking about whether I should put in a Mozilla Fellowship application this year, and if so what for. (Thanks to encouragement from lovely Mozilla staffers, following on from my grant from Mozilla last year, I've been pondering what form a fellowship might take. The initial application is extremely concise - feedback welcome, especially on how to shape a useful project which could be undertaken in a role as a practitioner, working on collaborative engineering and open IP, and therefore an active member of the community of practice at the same time.)

I'm not a hardcore co-operative person, and I think there's potential for other not-formally-co-ops to offer similar wins for the commons and for collective benefit. But all of these forms require business models and governance/incorporation structure that are not 'normal' for tech startups today. So much of our tech entrepreneurship narrative, support structures and resources (money, mentoring, training) are geared towards a very specific form of tech venture - one which takes investment capital motivated by growth and high returns. Supposedly this is also high risk, although the risk is often in marketing rather than technical risks.

How many potential or early stage entrepreneurs are aware there is an alternative path? If you are lucky you get to hear about social enterprises, which are still for-profit based on a similar investment (and generally exit) path, but with a mission stuck on the side. (I am exaggerating slightly here - there are many good social enterprises who have a depth of mission greater than profit+purpose - but the general tenor of a lot of enterprise support programmes is clear. You are basically following the same path - funding rounds, growth, exit, plus you may be working in a 'for good' market like health or education, or you may have some social benefit embedded perhaps giving a percentage of profits to a good cause.) And even if you know it's a possibility, you probably don't know how to go about it. You need resources (which do exist, somewhat, although they could be better signposted), and, as starting and growing a new venture is actually hard, you also need help - mentors, peers to encourage you along the way, and so on. Finding these is non-trivial, today, although networks such as the Zebra community help. There's no one specific business model or governance structure that is right; many challenges will be shared by co-ops, non-profits, hybrid enterprise structures, collaborative projects and commons initiatives - figuring out strategy, finding talent, securing resources. Whilst each of the specific communities may be starting out small it's especially important to nurture the fabric they exist within, making sure entrepreneurs can find the right support, even if it's not in the most relevant community. Networks and resources need porous edges so that frictions are minimised, and the overall movement can get started.

It feels like there is valuable work to be done:

- in raising awareness of co-operative and other forms of venture in entrepreneurial communities (at the earliest stages, because once you have incorporated or taken investment, you are pretty locked in).

- in making sure resources are available and findable, and which explain things to people who may not know anything about co-ops, or about charities/non-profits etc, and also which go into enough practical detail that you can find your way forward

- in connecting people with others who are figuring these issues out, or have done it before. Building the mentor network and communities of practice.

There's some other good thoughts on platform co-ops, the need for replication rather than scaling, and the capital challenges for them, in a follow up to Nesta's event from Leo Sammallahti. Leo also identifies a need for "lighthouse" institutions to help with, in essence, marketing new platform co-ops.

If you are reading this soon after I write it, consider writing to your MEPs if you have them, and push back on Article 13 (content upload filters) and Article 11 (link tax).

|

| https://twitter.com/debcha/status/1109801060196118528 |

Deb Chachra is also writing a book, and in the meantime has written a lovely twitter thread with inspirations about infrastructure and maintenance. Recommended.

A great article on end user programming, which can empower users by giving them more control over their tools (HT Martin Kleppmann), with some super insight into how to go about this practically (although it is very hard).

Richard Pope and James Darling reflect on ten years from the first ‘National Hack The Government Day’. I wasn't there in 2009 although many friends were. The diverse communities ( sharing, learning and challenging each other across boundaries) of those early efforts have evolved since, with many people moving into, and out of, key institutions.

That critical voice went quiet with the arrival of GDS, and it’s not clear what the equivalent platform is today.

It’s easy to see why. The word ‘innovation’ is rightly problematic in government.We could argue - as Lee Vinsel and Andy Russell over at The Maintainers, who I had a great call with this week, do - that it's problematic everywhere, right now. But back to Richard and James:

It is apparent more than ever in 2019 that the challenges digital presents are no longer limited to government. As a country, we need to invest in the digital renewal of the whole of our civil society — healthcare, unions, consumer rights organisations — any organisation that help people hold power to account or build genuine community and solidarity. We need to make them fit for the digital age. ....

The question we need to be asking ourselves in 2019 is: will a gradual, Fabian style approach get the UK to where it needs to be quickly enough? Probably not. 2019, more than ever, is not a time for patching.

I marched on Saturday with thoughts of revoking Article 50, taking some time to listen, reconnect and build bridges - within the UK as well as with Europe. The FT has a great piece tearing into a lot of the Brexit lines [paywall]; the New York Times has a piece about the nostalgia myths which got us here, on both sides.

I was struck mostly by the diversity of views and desires expressed on the march. A demand for a "people's vote" was, of course, well represented as a they had organised the day, but there were also main straightforward "remain" placards and banners, and quite a few "revoke Article 50" signs. Frustration with Theresa May, optionally the cabinet as a whole, or the Conservative Party, alongside frustration with Labour. I was also surprised by the number of local groups and communities who were marching together - towns and counties from around the UK, "votes for goths", scientists for EU, and so on. And the dogs - a lot of dogs against Brexit, broadly speaking.

Also in Sentiers this week, a link to this Vox piece on fashion in air pollution masks, as they become more prevalent in Western cities as well as Asia. After a day marching in London I was sneezing - which may be unrelated of course. I didn't spot any masks on the protesters - probably wise protest practice, although interesting given how many cyclists and others one usually sees in masks in London now.