Late weeknotes: emoji, surveillance capitalism, etc

On communications online...

Two articles about online gratitude (thanks to Nathan Matias, whose wisdom around people and communities online will be moving to Cornell later this year): Wikipedians thanking each other, and gratitude and the dangers of it in social technologies. (reminding me of notes on kindness from November)

Although we have a lot of images to communicate with, sometimes words are clearer. This article talks about common tasks, and the popularity of updating user interfaces for such tasks to follow fashion, at the expense of accessibility. I think digital design needs to be more respectful of our cognitive capacity to learn, understand and adapt to new interfaces; we all use a lot of digital tools and each change is a burden on our minds. It's worse for older people and those who are already under strain of other kinds. We can do better, in maintaining existing systems, or doing more up front work in design and good practice so that tools don't need endless reworks.

Emoji are changing pictorial language - a discussion of the change in recent years from ambiguous emoji, to very specific ones, and the changes in use that entails.

Counterintuitively, all these emoji are less applicable because they contain more information.

... they offer more evidence that emoji are transforming into a large catalog of fixed portraits, rather than a smaller set of flexible ideograms. That shift doesn’t just add to emoji; it also changes how they work.

The awkwardness of the interfaces used to access emoji amplify that change. Overwhelmed by choice, we’ve become more tempted to type in a word and have the device offer matches, as some emoji interfaces allow. That’s also how some text-entry systems for nonalphabetic languages work. But unlike logograms—pictures that represent a word or phrase, like those used for Chinese characters—ideographic emoji thrive when their meanings remain ambiguous. Matching icons to words encourages fixity of meaning, especially as it becomes harder to find any single emoji by scrolling.

Emoji are transitioning from pictograms to pictures. That change offers some obvious benefits, like the ability to create images that better represent a broader set of individuals and their experiences. It also shifts emoji’s function toward specificity and away from abstraction. Emoji is humankind’s weirdest and most successful ideographic language. If it is to become an illustrative one instead, that’s a revision worth discussing with words, not just celebrating (🎉), or lamenting (🙅), with pictures.

... It makes sense that emoji should strive to cover the gamut of human experience; more than half of human beings menstruate at some point in time, so that’s a good place to exert effort. But more specificity means less flexibility. That is, an emoji that shares other possible meanings, among them menstruation, is assumed by Palus and others to be a less desirable design choice than one with a singular, fixed meaning. That idea might or might not have political merit, but it does represent a shift in the way emoji have been conceived, approved, and used since the iPhone made them globally popular in 2010. The assumption that more numerous, more specific emoji are automatically better seems to be spreading, too.

An interview with Donald Knuth, one of the old guard of computer science, about how he manages to do scholarly work in the digital age (by avoiding email and electronic communications).

On his website, Knuth offers the following explanation for his refusal to use email: “Email is a wonderful thing for people whose role in life is to be on top of things. But not for me; my role is to be on the bottom of things.”Food for thought whilst I'm back in academia for a bit, and seeing the conflicting demands on researchers, and how communications and organisation works (in contrast to other settings I've experienced). I am acutely aware of my continuing status as a young man in a hurry (as featured in Microcosmographia Academica), though, so my thoughts on how the University could do better are probably not helpful.

Tim Harford wrote in December in the FT about finding a better level of tech usage - cutting back, slowing down, reflecting on what's necessary.

since social media is supposed to be about connecting with far-flung people, and since Christmas was looming, I decided to start writing letters to include with Christmas cards. I couldn’t write properly to everyone but I did manage to write serious letters to nearly 30 old friends, most of whom I’d not seen for a while. ... The letters were the antithesis of clicking “Like” on Facebook.I've written Christmas notes/letters for many years, so I can't adopt this practice. I'm continuing to noodle at ideas around cadence and types of interaction on and offline, though, and I'm making a conscious effort to have tea (in person, or more often, over Skype or similar) with people I don't see very often.

I realise I am tweeting less, possibly because interesting tweets end up in weeknotes with some attempt at commentary or synthesis. As my Twitter readers (at least, in terms of the people who sometimes 'engage' with likes or retweets, and who therefore I'm aware of) are a pretty diverse lot, this perhaps makes sense - a retweet doesn't tell you much about why an article or idea about a field you aren't in yourself. When I'm scanning twitter I'm not usually thinking with any depth and so adding a thoughtful comment isn't always straightforward. Increasingly I don't read articles I find via Twitter straight away - I just note the links for later reading. On the other hand, more people probably see my tweets than bother to read weeknotes, so perhaps my "bridging" activity is less effective now? Perhaps I am overthinking this sort of thing.

Crossing sectors and fields is hard work, but useful in giving me a rich sense of the complex landscape of things and where plans, ideas and strategies might fit. And of course it is always fascinating to get insights into how different groups/communities/disciplines work. Perhaps I should have been an ethnographer.

Two random reminders of how easy it is to be unaware of hugely popular things, or even of categories of popular things: a YouTube fashion star with 14 million followers visited Birmingham and caused gridlock and millions attended a virtual concert by Marshmello in Fortnite.

------------------------------------------

Like others, many of whom have been working on this for much longer than me (and even I was doing it before it was cool), I'm getting a bit tired of the hot air filled 'tech ethics' discourse. Not enough tech in it and not enough ethics, and not much of it doing more than skimming the surface. Projects like the revised ACM Code of Ethics, which involved actual ethicists as well as computer scientists, and sought a pragmatic result which could actually be useful, or like Doteveryone's forthcoming TechTransformed, are all too rare. There's no question that there are some tough questions about how far you go in working out what good looks like. What kind of data uses are OK? Do we need to ban all targeted advertising? Are we screwed unless we make radical changes to the world of finance, investment and markets, or reform what it means to be a business? Only with a sense of how far we want to go can we work out what interventions might be worth trying. And that requires an awareness of the pressures in the opposite direction - the inevitability of people who want to amass money and power, people who won't care about ethics until the bottom line is seriously affected. So I was glad to find a very different perspective on this.

|

| https://twitter.com/sabelonow/status/1083373318483464192?s=19 |

Ethics is not missing in technology. Our ethics and values are always present in the creation and use of technology. The technology society creates and chooses not to create is a window into the ethics and values of the powerful. The technological feats and the business models that sustain them are a mirror to the priorities of the few who hold the capital and capability to create technology.....Ethics is applied through power. When technology companies, for instance, in the process of amassing power, harm society (socially, economically, politically), it is not just an oversight, it is an insight into their ethics – It is an insight to power at work under individualistic values.

A lecture from Danny O'Brien on the way internet regulation has got where we are today, and the values underpinning it all - fascinating stuff, and a good example of the history so much of the current debate seems unaware of. This ITU presentation from Geoff Huston also highlights the history of the underlying technology architecture of the internet itself, and how that has shaped the business models and market dominance we see in the Big Tech companies now. Another piece of useful context for understanding the regulatory landscape, and the tools available to us - which go far beyond the surface of content interventions.

More from Anand Giridharadas, this time on AI:

I think the conversation around AI is like talking about icing in the absence of a cake. The problem is that society is not working for most people. Society rewards the views of Exxon Mobil more than the people who don’t want dirty rivers. AI arrives as this new-fangled thing and all it’s going to do is accentuate and aggravate the existing problems. ....Shoshana Zuboff spoke at a Cambridge event hosted by the Trust&Technology Initiative in early February. She was a compelling speaker, and her icebreaker of asking the audience to shout out single words which described why we were there was intriguing.

There’s a false story at the moment about the easiness of making change now, this notion that what used to be done by fighting on issues of power, justice and rights, can now be achieved by a social enterprise or an app.

I haven't properly read the much discussed Morozov review of her book; I came across a more structured scholarly critique. The curse of very long books is that it's much more appealing to read the reviews than heft all the paper around. I think Zuboff's popularisation of the surveillance capitalism framing and attention-raising around the issue is useful, regardless of the quality of the book itself; as ever, I'm interested in exploring other models for internet services, which avoid this, and which also avoid structures exacerbating inequalities between rich and poor. I did enjoy the James Bridle review in the Guardian though:

Zuboff recasts the conversation around privacy as one over “decision rights”: the agency we can actively assert over our own futures, which is fundamentally usurped by predictive, data-driven systems.Agency is perhaps a more compelling focus for digital rights campaigning than privacy, which hasn't got traction with most people despite the efforts of many over the last couple of decades.

But then, reading Diane Coyle's review of Cass Sunstein's On Freedom - maybe nudges can be a form of freedom? (I do read books, not just reviews, honest.)

We also have surveillance humanitarianism -

|

| https://twitter.com/seanmmcdonald/status/1092863127438454786 |

The World Food Programme's engagement of Palantir has been strongly criticised by civil society groups this week. It is perhaps not surprising that the world of humanitarian aid is following in the footsteps of 'best practice' from big business and tech business - the drive to gather and use data, to scale projects, to optimise efficiency, to innovate (whatever we think that means). Are we sure this is the best way to do aid? Is a business mindset - especially one from our current form of capitalism - the right way to think about social change?

Blitzscaling has been a Silicon Valley concept for a while - taught at Stanford since 2015. It's encouraging to see Valley insider Tim O'Reilly criticising it, especially as ventures outside the capital-rich environment of the Valley are encouraged to adopt it. As O'Reilly says, sometimes it may be an appropriate approach, even for non-profits, but it is perhaps oversold.

------------------------------------------

Inc magazine has an article where Peter Drucker tears down the delusion of American dominance in entrepreneurship. He also has some great points about social entrepreneurship.

In this country we by and large still believe that entrepreneurship is having a great idea and that innovation is largely R&D, which is technical. Of course we know that entrepreneurship is a discipline, a fairly rigorous one, and that innovation -- an economic not a technical term -- has to be organized to create a new business. That's not news. In fact, it's what made Edison so successful more than a century ago. But American businesses with few exceptions -- Merck, Intel, and Citibank come to mind -- still seem to think that innovation is a "flash of genius," not a systematic, organized, rigorous discipline.

.... [Non profits] need more not less management, precisely because they don't have a financial bottom line. Both their mission and their "product" have to be clearly defined and continually assessed. And most have to learn how to attract and hold volunteers whose satisfaction is measured in responsibility and accomplishment, not wages.

... Inc: I suppose it depends on one's definition of entrepreneur.

Drucker: There is only one definition. An entrepreneur is someone who gets something new done.

------------------------------------------

Bits and pieces.

Steve Song on affordable internet access - and how local services contrast with global ones. I love the photo - the next big thing will be a lot of small things. Maybe we are approaching a tipping point, where scaling (let alone blitzscaling) isn't the be all and end all of so many initiatives, not just tech startups.

Logic Magazine on a theory for how cities die, which has proven dangerously influential - and inspired SimCity.

Largely forgotten now, Jay Forrester’s Urban Dynamics put forth the controversial claim that the overwhelming majority of American urban policy was not only misguided but that these policies aggravated the very problems that they were intended to solve. In place of Great Society-style welfare programs, Forrester argued that cities should take a less interventionist approach to the problems of urban poverty and blight, and instead encourage revitalization indirectly through incentives for businesses and for the professional class. Forrester’s message proved popular among conservative and libertarian writers, Nixon Administration officials, and other critics of the Great Society for its hands-off approach to urban policy. This outlook, supposedly backed up by computer models, remains highly influential among establishment pundits and policymakers today.

SustainableUX happened - a fully online conference. This is good for the planet - fewer flights - and good for people who have caring responsibilities at home.

It's not often you see senior business executives reflecting openly about the experience of losing your job. Marie Claire has a feature on Beth Comstock, and I was particularly struck by her comments on networks.

She noticed social changes too. “People who were your friends, certainly your work friends, they vanish,” she says. “That’s sad, right? They only liked me because they thought I was going to get them business or that I could get them here or there.” Logically, she says, that made some sense to her—“Time is short,” she explains—but emotionally, “some of the people did surprise me because I thought we had a different kind of relationship.”

... “No matter where you are in your career, try to make sure you’re developing your own story,” she says. “I was the face and voice of GE for so long, yet I had to work to establish my personal network. It served me well, post-GE, that people knew me in a broader context.”

Comstock began to feel that her new position—or non-position—was freeing. When she attended a cocktail party with a friend, he paused before going in. “He’s like, ‘How do I introduce you? I can’t just say, Here’s Beth Comstock.’” But I am Beth Comstock, she thought to herself. She now makes a point of not discussing work roles with new acquaintances.

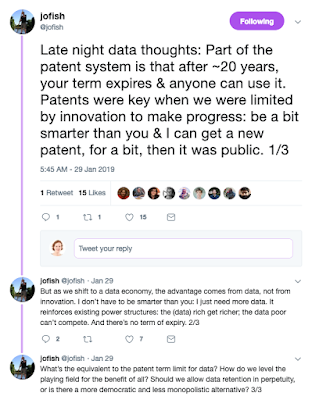

I liked this thought about data and innovation equity from jofish:

|

| https://twitter.com/jofish/status/1090123785620008960?s=19 |