weeknotes: machine intelligence beyond deep learning, slogans and demos

Everyone following machine learning / AI stuff will probably have already read these and the inevitable twitter threads, but I thought there was an interesting common thread between Gary Marcus’s piece about the problem with deep learning and Beth Singler’s about AI, storytelling and social intelligence. Marcus questions “the notion that deep learning is without demonstrable limits and might, all by itself, get us to general intelligence, if we just give it a little more time and a little more data” and Singler takes a different angle on what today’s focus on data-driven AI might be lacking. The potential power of symbolic AI, unlocked by the level of processing we have access to today, seems to have been forgotten.

In the “tech world” there’s so much hype around machine learning, and the incredible benefits it is supposed to bring, that it’s easy to forget that you need good data to feed such systems, there need to be useful insights in that data, and then you have to have a way to realise value from those insights. It seems all to easy to forget that just adding machine learning to a domain won’t necessarily unlock lots of utility, so I’m glad to see more people talking about the limits of the current bubble.

(What is “tech” anyway? It used to be the industry I thought I worked in, but I’m not so sure now. “Big tech” is Amazon, Google, Facebook, Apple these days; big tech used to include Arm, Intel, AT&T, IBM, and so on. Some of these are still big, still necessary for today’s world (Arm are everywhere, still) but less visible consumer brands seem to count for less now. Is Arm a tech company? Or is ‘tech’ increasingly just ‘consumer tech’? What should we call all the rest of it? Especially the bits which aren’t enterprise IT, or semiconductors, or telecommunication networks…)

Whatever ‘big tech’ is, it’s good at persuading people that it is a force for good. Maria Farrell looks at tech slogans, and the way they both describe and shape what is done in businesses:

Google knows that organizing all the world’s information is creepy as hell. But it is driven to keep trying, whatever the cost. The slogan simply makes visible the company’s DNA.…

Why can’t powerful organizations seem to avoid slogans that are actually quite chilling? Partly because language is multivalent, and meanings multiply.

Tech likes demos, as well as slogans. My most interesting conversation last week was with a historian. Simon Schaffer helped me build a different perspective on technology development through the ages (since the 18th century, when the world of investment shifted): the invisibility of the engineering brains in the backroom, the showmen and their proofs of concept supporting their efforts to raise capital. The line between proofs of concept (or demonstrators, or prototypes) which actually prove something, demonstrating a technical capability that didn’t exist before, and smoke and mirrors pieces to persuade investors (private or state) or customers or the market at large, is a blurry one. I was left thinking that I don’t know enough history, or even enough about how history as a discipline works.

And in terms of showmen, this week’s concerns about Facebook shouldn’t be a surprise, as all these partnership deals were showcased when they were set up — for instance, at Facebook’s big developer event F8 in 2011. Which opened, oddly, with a skit, about user growth and people sharing information. (HT Stratechery)

Is tech too easy to use? Nice to see this NY Times piece echoing something we’ve talked a lot about at Doteveryone. One common bit of frictionless design in tech design is the “click to agree to the terms and conditions” — where it’s all too easy to just click through. Consent doesn’t work anyway, as Martin Tisné argues in this article about data rights — making good points about the need for future-proofing what we design and require today. A good counterpoint to the excess focus on today’s concerns in the personal data space, without thought to tomorrow’s.

Will people leave Facebook in large numbers after this latest set of scary headlines? Probably not. We all use systems we don’t trust, and the value of sharing with friends and family is too great, especially when you realise the limited privacy gain which stopping doing so gets you. Brian Krebs summarises this nicely:

Reality #1: Bad guys already have access to personal data points that you may believe should be secret but which nevertheless aren’t, including your credit card information, Social Security number, mother’s maiden name, date of birth, address, previous addresses, phone number, and yes — even your credit file.

Reality #2: Any data point you share with a company will in all likelihood eventually be hacked, lost, leaked, stolen or sold — usually through no fault of your own. And if you’re an American, it means (at least for the time being) your recourse to do anything about that when it does happen is limited or nil.

Marriott is offering affected consumers a year’s worth of service from a company owned by security firm Kroll that advertises the ability to scour cybercrime underground markets for your data. Should you take them up on this offer? It probably can’t hurt as long as you’re not expecting it to prevent some kind of bad outcome. But once you’ve accepted Realities #1 and #2 above it becomes clear there is nothing such services could tell you that you don’t already know.

Once you’ve owned both of these realities, you realize that expecting another company to safeguard your security is a fool’s errand, and that it makes far more sense to focus instead on doing everything you can to proactively prevent identity thieves, malicious hackers or other ne’er-do-wells from abusing access to said data.

Highlighting mine — we need to think more about preventing bad outcomes and abuses of use, rather than access.

Security isn’t easy for big firms, either, and maybe insurance isn’t the reassurance it once was: a big insurer argues that NotPetya was a hostile or warlike act by a government or sovereign power, and is therefore excluded from coverage. Ouch.

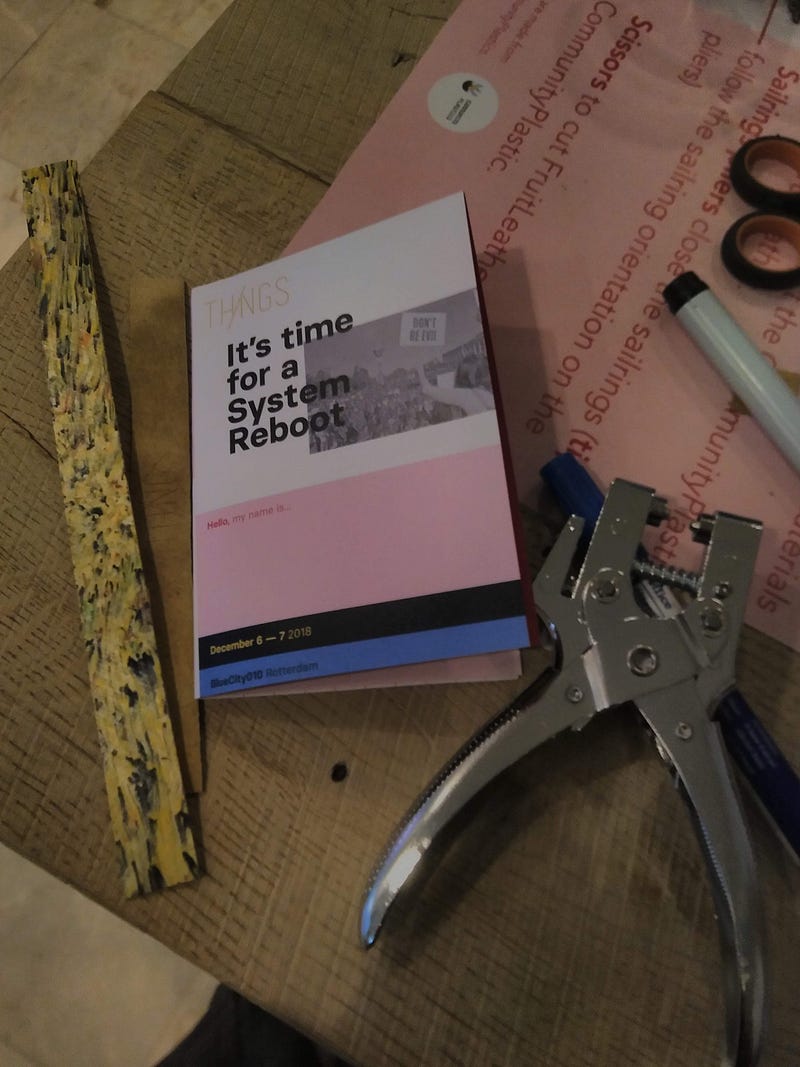

I had a great time at Thingscon in Rotterdam, catching up with folks working on the internet of things around Europe. Highlights included designing and making my own badge, and one of the better panels I’ve encountered discussing what responsibility means for technology. It stands out for me as an event because of the diverse attendees (designers, developers, researchers, policy people, even police and government workers), combined with a fairly clear sense of shared cultural purpose (even if there were also different views about how that purpose might be realised). The European flavour was also novel for me outside an academic context — this was not a global tech event, nor an American-dominated one. (You can watch me talk too quickly about responsibility in tech here.)

Phil Gyford writes about how no one today would invent post boxes and the postal service, or public libraries. I think I’m a little less pessimistic — whilst our current government is not up to serious public investment in this sort of thing, there are other ways we can create public goods. I think we have new organising powers and information sharing capabilities which will/are enabling entrepreneurial types to create new community ventures which can happen locally, but be interconnected usefully. Just this morning I was talking to one of them :) It’s harder, to build community value and public goods; you don’t get to follow the nice playbooks of the tech startup community for instance, but have to seek out new business models and structures.