Monthnotes: carbon removal, COP26 IP, corporate culture

DW has a great article about the sustainability of wind power - covering all the aspects from recycling turbines, to bird fatalities, to mitigations such as "a ring of tiny air bubbles used during construction activities that dampens noise by around 90%". Thanks to Joanna Bryson.

Laurie Macfarlane writes about land. Highlights mine.

Although there is much hype around the promise of impressive Negative Emissions' Technologies (NETs), such as carbon capture and storage, to date the only proven NET is the restoration of forests, peatlands and other natural carbon sinks. ... In the case of carbon emissions, the approach enables those who invest in projects that will sequester carbon from the atmosphere to claim carbon credits (or carbon ‘offsets’), which can either be ‘netted off’ against the owner’s emissions, or sold on to other emitters via emissions-trading schemes.

... over the past decade, a number of large-scale emissions-trading schemes have been established or expanded upon, including the United Nations’ REDD+ program, the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism and the EU’s Emissions Trading System. To date, however, these schemes have largely failed to reduce emissions on the scale that was envisaged.

... At COP26, new rules were agreed to establish a unified international carbon market... And corporate and financial investors are quickly realising that profiting from this modern gold rush requires one thing above all else: access to land – and lots of it. As a result, global investment in rural land markets is soaring... few places are attracting as much interest as Scotland... Scotland has a large rural land area: 98% of the country’s landmass is classified as either ‘remote rural’ or ‘accessible rural’. One-fifth of the country is peatlands... More than eight in every ten Scots live in the 2% of the landmass that is urbanised.

Significantly, however, ownership of this land is highly concentrated. As with the UK as a whole, the archaic patterns of land ownership that were in other nations swept aside by revolution and revolt survive largely intact in Scotland to this day. ... just 432 individuals own 50% of Scotland's privately held land....Land markets across the UK also remain notoriously lightly regulated, meaning that anyone in the world can buy land with little scrutiny.

... According to critics, however, enabling companies to offset their emissions in this way amounts to little more than greenwashing on an industrial scale. The fact is, they argue, there is simply not enough land in the world to offset global emissions, so allowing companies to boost their green credentials by investing in carbon offsets acts as a dangerous diversion from the immediate need to reduce emissions ... If the entire global energy sector was to set similar net-zero targets, an area of land nearly the size of the Amazon rainforest would be needed, equivalent to a third of all farmland worldwide – which would risk pushing millions deeper into food poverty.

... Behind the flowery rhetoric about ecology and sustainability, there are growing concerns that the rapid growth in land purchases for carbon offsetting will push up land prices and rents, displacing local communities while exacerbating an already highly financialised land market. In many cases, this appears to be an explicit part of the business model. ... As Peter Peacock, a former Highlands and Islands MSP and veteran land reform campaigner, recently put it:

The Highlands are once again being sold from under the feet of local people to external forces who can out-compete other interests for land, forcing up land prices, and undermine communities in their ability to take a lead in tackling the climate emergency while also promoting wider social and economic benefit under local democratic control.

... The Land Reform Act of 2003 introduced the Community Right to Buy in Scotland, which empowered local communities by giving them the first option to buy land when it was put up for sale. To date it is estimated that around 560,000 acres (or 2.9% of the total land area of Scotland) have been taken into community ownership. Despite this relatively small footprint, many of these communities have pioneered innovative and inclusive approaches to tackling the climate emergency.

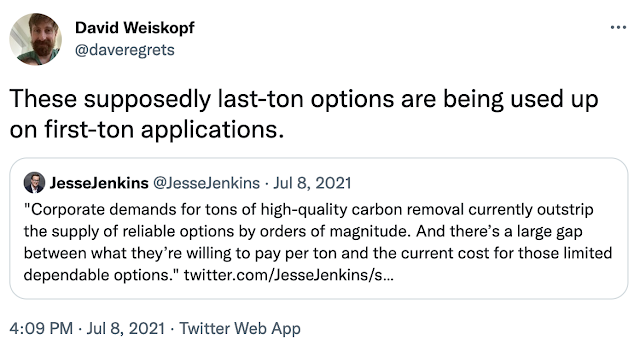

I ended up following tweets and reached -

|

| https://twitter.com/daveregrets/status/1413153262321102860 |

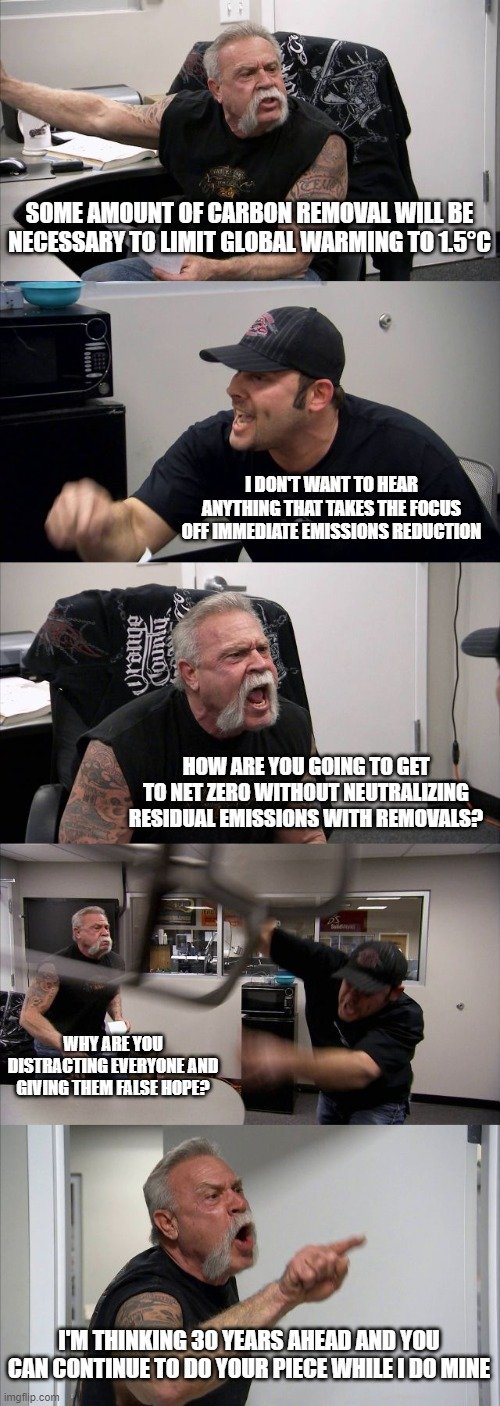

and thank you Richard Waite for this tweet with a lovely meme:

Which brings us back to the original tweet that got me thinking on this:

|

| https://twitter.com/mrchrisadams/status/1463532345072492547 |

Such useful terms:

|

| https://twitter.com/daveregrets/status/1413153206524203013 |

Also enjoyed this on carbon neutrality of luxury items:

|

| https://twitter.com/daveregrets/status/1408075302060756997 |

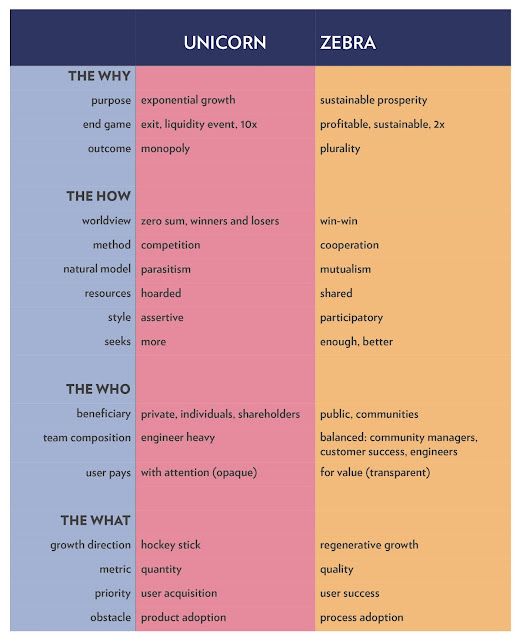

I finally got around to formally joining Zebras Unite - I've been in the community practically since the start, but only just joined the co-op. The groups on alternative capital, co-owned digital infrastructure, and exit-to-community are really special and interesting. Very excited to see what we can build - here's the vision, compared to the 'classic' tech venture 'unicorn':

|

| https://twitter.com/Zebras_Unite/status/1469367704398319621 |

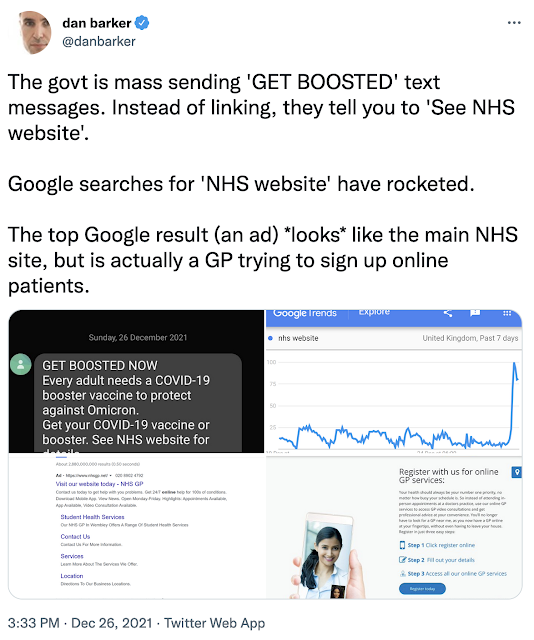

A fascinating thread about what people search for about the NHS (eg one popular set of searches are about NHS staff benefits! who knew), inspired by:

|

| https://twitter.com/danbarker/status/1475127632350093318 |

Why aren't we doing more to improve air quality and ventilation, to reduce infection spread (aside from any other wellbeing benefits)? This BMJ editorial notes that we may be starting to add 'ventilation' to Covid policy documents, but there's not much practical change happening around actual air.

While keeping your distance, wearing a mask, and getting vaccinated have provided much protection, one intervention that would have a significant impact is adequate indoor ventilation. Healthcare, homes, schools, and workplaces should have been encouraged to improve ventilation at the very beginning of the pandemic, but tardy recognition of the airborne route by leading authorities in 2020 stalled any progress that could have been made at that stage.91011

Another major compelling reason that air quality has been side lined is cost. Most buildings are neither designed nor well operated from the air quality aspect, with energy conservation and thermal comfort at the top of the list of requirements.1617 Pumping in adequate amounts of fresh outside air, however engineered, will challenge running costs as well as carbon status.18 Outdoor air generally differs from indoor air in terms of temperature and humidity, and conditioning outdoor air needs significant energy.

Additionally, ventilation is usually controlled by building operators and owners, not necessarily individuals, and the former are not yet mandated by law to improve ventilation in public venues.18

Ventilation and air cleaning systems are noisy, drafty, and require fine tuning and regular maintenance.19 Even simple window opening invites discussion over chill, airflow, and security. ... existing ventilation standards hardly consider the risk of airborne infection in non-specialist public spaces at all.

... Clearly, better ventilation requires planning and investment, but who is going to ensure this and how should it be done? Upgrading internal air quality for billions of indoor environments in the world needs solid research, funding, and mandated standards. Those that we have are variable or are applied inconsistently. We have established public health strategies for foods and water and even pollution, but air quality inside most public venues in our communities resembles nothing more than miasmic uncertainty.1415

|

| https://twitter.com/natematias/status/1474146321523253258 |

|

| https://twitter.com/Sean_ORiain/status/1475518779442577412 |

A thread of depressing stats about the inequality in Cambridge. Even before the pandemic, over 33 thousand children living in poverty in the city, and so on. I remember muttering about the shocking state of local inequality and poverty to a Pro Vice Chancellor at the university in 2018, when there was much enthusiasm about the benefits Cambridge research could supposedly bring to other parts of the world, and the Cambridge Global Challenges initiative was being set up. I suggested we ought to show we could address our own problems first...

Indeed, inequality in Cambridge has been a thing for a while. The University perhaps has not made as much difference as it might like to think; here's a recent Ars Technica article "Medieval skeletons tell story of social inequality in Cambridge":

The research stems from the After the Plague project at Cambridge University's Department of Archaeology, which explores how historical conditions influence health and how health, in turn, shapes history. The project particularly focuses on the Black Death period (1347-1350 CE) in later medieval England, which wiped out between a third and a half of Europe's population.

"By comparing the skeletal trauma of remains buried in various locations within a town like Cambridge, we can gauge the hazards of daily life experienced by different spheres of medieval society," said lead author Jenna Dittmar, a paleopathologist at Cambridge. "We can see that ordinary working folk had a higher risk of injury compared to the friars and their benefactors or the more sheltered hospital inmates."

By the 13th century, Cambridge was a thriving market town with an active river port and a rural agricultural component on the outskirts of town. Its famed university had only just been founded. "Although a small town by today's standards, Cambridge presented a varied social landscape," the authors wrote.

Diane Coyle was interviewed by Ruth Ben-Ghiat. Highlights mine:

Obviously, inequality has been long in the making, and weakened enforcement of labor laws, weakened unions, the erosion of minimum wages, and facilitations of illicit financial flows have all contributed to it. It is quite interesting that a lot of the very wealthy are now in effect illegal people. They're using money laundering techniques and stepping outside the boundaries of what most jurisdictions legally allow.

... The current framework of measurement was devised during and after World War 2. That matters because we are kind of reaching the end of the road in how much we can take nature for granted in our own economic and other activity, whether that's climate change, tipping points in ecosystems, or lack of clean water. There's also the issue of unpaid women's work in the home. That's been excluded, along with all other non-market activities, even though these are fundamental to our lives.

Digital activity presents a similar problem, because some of the categories of digital activity are not easily handled by markets: they've got the characteristic of public goods. Data would be a great example. We've got to put in the work to measure all those previously unmeasured things, just as we did in the decade after World War 2.

You can buy a beautiful poster to Honor Domestic Work "This poster is a way to show our appreciation to the people in our lives who do the work that goes unrecognized— caring for our children and loved ones, keeping our homes clean, managing household details like grocery lists, cooking, repairs, appointments, and the everyday essential that we need to care for ourselves, our families and communities." Check out the (US) stories too.

Some great news:

|

| https://twitter.com/Petercampbell1/status/1467787705362878465 |

Frank Tietze was at COP26, and wrote up a long article about the experience. It was an interesting perspective, both in that he was at some of the 'real' negotiations, and also that he was looking for Intellectual Property aspects in it all.

Attending COP26 on behalf of our IPACST project and as steering group member of Cambridge Global Challenges (also for Cambridge Zero and CISL), I was not sure what to expect, really. I had the slightest suspicion that IP would not be discussed very much, at least not mentioned often explicitly. This does not come much as a surprise, even though IP underpins almost any aspects of our daily lives and industrial activities in our economies.

... One panel member said “scale up is incredibly important… deploy, deploy, deploy”. When it comes to accessing technologies that are already available it seems from an IP perspective we should be asking which licensing models can help to accelerate the deployment and adoption processes. Would patent pools possibly play a role here or patent pledges, such as the Low Carbon Pledge? Alternatively, should governments maybe consider supporting or guaranteeing royalty payments at a certain rate? Do we need specific templates and guidelines for IP licensing of green technologies? Almost certainly, whether existing or not yet developed technologies, these are all likely to still have to go on a development trajectory to improve efficiencies, which probably involves a set of cumulative, incremental improvements, so inventions that might be protectable by IP rights. Hence, we might need to be getting more creative about this.

... CTCN is a technology transfer organisation that seems to be running 350+ technology transfer projects dedicated to climate change mitigation and adaptation technologies supporting 100+ countries. As with any technology transfer project, I would strongly suspect that CTCN somehow needs to face and address IP issues, maybe with contractual arrangements. ... I had a quick look at the latest CTCN annual report searching for “intellectual property” related terminology, but the search returned no results. However, with a bit of searching I found this CTCN report from 2021 that actually defines the receiving technologies as endogenous technologies and the capabilities being transferred into the receiving country as endogenous capabilities. As it turned out, across three surveys IP actually was mentioned as challenging. While it did not come out on top, it comes out amongst the top challenges. The report also concluded that “the importance of intellectual property rights depends on the nature of the technologies involved.”

The NDEs and TNAFPS put intellectual property rights for modifying existing technologies in the top half of the most important measures, while IPRs for developing new technologies was ranked much lower.

Overall, the lack of mentioning of IP in CTCN related discussions turned out to be a bit puzzling.

... This reminds me of the idea that I wanted to suggest already to the colleagues of Lens.org .... that one should include a simple search function (maybe just a switch to flick) in public patent databases that allow to easily and quickly (so for the non patent expert) to find technical solutions that are not protected in a certain country or are off patent (e.g. more than 20 years old or for which the owners have stopped paying renewal fees).

In Frank's follow-up article, I love this note on UN language :)

I went on to attend more “informals”, which are the meetings where the negotiations actually happen. ... Because of a possibly deadlock, the session head to break for a few minutes so the delegations could have some informal-informal discussions (yes, right! No mistake. The sessions are called informals, so the short breakout discussions are then called accordingly informal-informals).

I also learnt more about the different COP parties and understood what RINGO is, i.e. the party of Research and Independent Non-governmental Organisations. I had picked up that RINGO has a briefing session each morning... When I arrived to the session the discussion was all about innovation. I even got to ask a question... I wanted to find out whether there is existing work going on about the IP issues that are specifically concerned with adaptation, respectively mitigation technologies. The response I got from RINGO was “This sounds as an excellent research question”.

Ah :)

... One topic that I seem to miss not only in the reports, but also from what I heard so far is the acknowledgments that also LDC and LMIC can be innovative and contribute to the development of adaptation or even mitigation technologies. Occasionally, I read it was acknowledged that poor countries can adapt technologies to local needs. I suspect this might lead to modifications and possibly to some, probably mostly incremental innovations. However, that’s certainly not all. I strongly suspect that LDC and LMIC are capable of developing what might be called frugal innovations (see the literature on frugal innovation, e.g. by colleagues Tiwari and Herstatt of TUHH), but also social innovations. So if this is the case, certainly local inventors should be rewarded for their ingenuity. This might be where IP would also play a role.

It feels like there must be a lot of potential here to get technologies to where they can be useful, and IP is a key part of that given how the world works today. Covid vaccine IP may or may not be a useful example...

Huh - kind of predictable maybe when you think about it, but still:

|

| https://twitter.com/nicoleperlroth/status/1474275566572347393 |

Ah, corporate lawyers:

|

| https://twitter.com/mer__edith/status/1471935457839796224 |

Yup:

|

| https://twitter.com/natematias/status/1468002942393503751 |

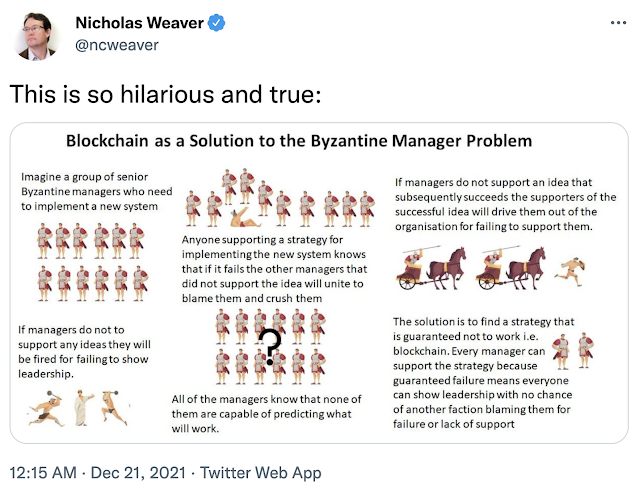

Large organisations are often like this:

|

| https://twitter.com/ncweaver/status/1473084555976273924 |

Thanks to Skyler Adams for leading me to this GarbageDay email newsletter stats post, which includes the following gem:

Though, perhaps the most interesting takeaway from this — beyond American social media users’ insatiable need to laugh at and ridicule and dissect viral clips of unwell people having some kind of crisis on an airplane, even if those clips turn out to be scripted — is how jarring Facebook-optimized content is to the wider internet. After a decade of algorithmic tweaking, content that does well on Facebook is now so completely insane looking that it continually causes moral panics and knee-jerk outrage when it’s viewed by users not accustomed to it.And with that I have caught up with things I read in 2021, with the exception of a bunch of things about DAOs that I have saved up.

It’s also very interesting that as this cat breastfeeding video was going viral, Facebook/Meta announced that the top publications on its newsletter product Bulletin have around 5,000-10,000 readers, which is very low for a platform Facebook’s size. But we know what kind of content does well on Facebook. It’s not a newsletter written by Malcolm Gladwell, it’s a 15-minute live video of Taylor Watson [Vegas stage performer] slowly revealing the results of her breast augmentation surgery that ends in a punchline that she has chicken breasts taped to her chest.