last-month Notes: voting, health and tech, ruggedising

David Runciman in the Guardian argues for lowering the voting age - to six:

There is now a set of vicious circles at work. Once politicians representing older voters start winning elections time and again, the young are discouraged from voting, which only makes the political imbalance worse. If young people pursue social mobility by moving to places where other young people are, they increase the likelihood that older voters will dominate electoral outcomes everywhere else. The result will be governments and policies that work against the sorts of social mobility that younger voters tend to favour. This has been the pattern in Britain for the best part of a generation. Pensions will get protected while student debt goes unaddressed. The interests of mortgage payers will be prioritised over the interests of renters. A country in which more than 70% of the under-30s voted to remain in the EU will still choose to leave.

Three posts about MySociety and where they are going next - really positive to see this iteration. Start with this one. I like the focus on the "dual crises" of democracy and climate. One of the three 'shifts' is "Place more power in more people’s hands, not just make old power more accountable" which also feels like a great evolution from the open/civic tech space of 5-10 years ago. Hope they can make it real -

Why: We believe people can and want to work together to build a fairer society – the web can help do this at scale.

How: Our role is to repower democracy: using our digital and data skills to put more power in more people’s hands.

What: We work in partnership with people, communities and institutions to harness digital technology in service of civic participation.

Major banks in the UK and their relationships to financial crimes are explored in this thread from Ben Chapman. I didn't realise so many finance sector companies donated large sums to the City of London police.

Grim stats:

|

| https://twitter.com/rory_deighton/status/1465666476258570250/photo/1 |

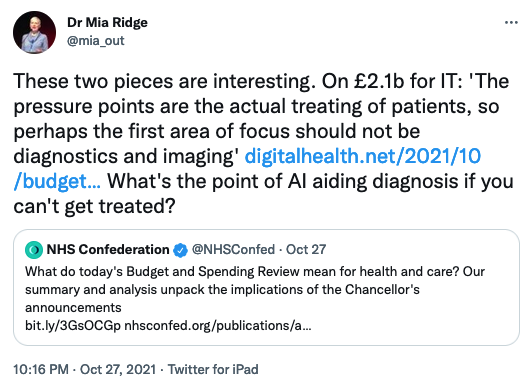

All the excitement about AI for health, at least in the UK, seems to be missing the point about the realities of healthcare today:

|

| https://twitter.com/mia_out/status/1453470763298828290 |

Relatedly -

|

| https://twitter.com/marcus_baw/status/1456973501059977217 |

James Hayes writes about the state of AI.

With the publication of its National Artificial Intelligence Strategy (NAIS), the UK joins the roll of nations jostling to assert ‘superpower’ status in the field of AI. Published in September, the government’s 10-year plan is founded on the contention that competitive pre-eminence in AI is a “top-level economic, security, health, and wellbeing priority [that is] vital to national ambitions on regional prosperity and for shared global challenges”.

Its view is backed up by a 2019 study by McKinsey that reckoned AI could deliver a 22 per cent boost to the UK’s GDP by 2030, but the country will have to show strong competitive prowess to win AI market share away from rival nations: at least 25 countries have already launched their own strategies.

The article is fairly critical of the gaps and oversights and missing definitions in the NAIS, around all kinds of topics from what businesses work in AI to investment, national impact, and how one can tell whether what you are buying is AI, or any good. The most memorable bit was highlighted by Ian Brown:

According to Wim Naudé, professor of economics at University College Cork, “AI is not making advanced economies more productive. Even [...] firms [that] are among the top investors in AI and whose business models depend on it – such as Google, Facebook and Amazon – have not become more productive.”

This contradicts claims that AI will inevitably enhance productivity, says Naudé. “Related to this is the fact that most AI applications just are not that innovative,” he has said. “Firms do not adopt it, not because they do not trust it, but because it makes little business sense.”

A 2014 solar power system for a village in India fell into disuse. Batteries could not be replaced or maintained; thermal (coal-fired) power was cheaper (when grid connection was available), and the solar system didn't support some appliances. Wind turbines in Tamil Nadu are also unmaintained and failing, and there's no money to replace ("repower") them.

Simon Wardley wrote a provocative thread about what we need to do about climate - to start talking about people, not tonnes. Thanks Marcus Baw for sharing. I struggle with Wardley somehow, I always want to like his maps system but they seem so hard to create for a new context compared to the "look it's obvious" nature of the examples.

|

| https://twitter.com/LeoHickman/status/1459496479987490820 |

Good to see this -

|

| https://twitter.com/ClientEarth/status/1459167711003619338 |

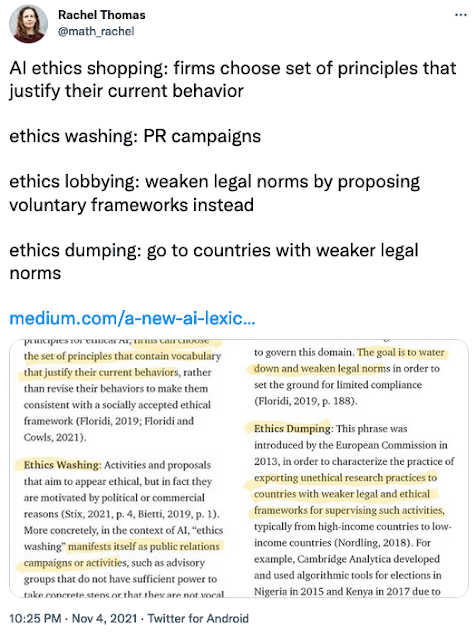

Useful reminder of special language:

|

| https://twitter.com/DrSimEvans/status/1458432308193767427 |

|

| https://twitter.com/math_rachel/status/1456387028946284548 |

Rich Bartlett, who co-ran the microsolidarity course I attended a couple of months ago (which I'm still digesting) writes about groups working at different scales in this twitter thread. This is such an important idea - and means that 'scale' as a goal or even a good idea needs to be questioned in a community/group context.

Internet governance in places such as the IETF is often described as open and it is, up to a point. I liked this framing, which I found via Niels ten Oever:

|

| https://twitter.com/C___CS/status/1463129172172288012 |

We live, today, in a world where some people worry about their family surviving the trip to the next source of water, and others fret over having to buy their second-favorite brand of coffee. ... I call this reality a transapocalypse. A transapocalypse is a spectrum. Some parts of the world will experience death and suffering and tragic upheavals as horrible as any humanity ever seen, even while others experience unprecedented prosperity.

... For all the millions of people finding themselves pulled into apocalyptic situations, there are also millions of people living high and dry and pulling in greater and greater returns on their investments. Many are already reacting to the upheaval around them with lifeboat thinking — seizing what they sense will be needed and limiting access to it for their own benefit.

We increasingly live in a world of refugee camps and luxury survival compounds. There is a boom in private security services, private fire services, independent medical care, the ability to use investment commitments to buy multiple passports to give you a bolt-hole somewhere like New Zealand, Malta or Switzerland — a vast industry rising to provide private protection, for the wealthy, from the impacts of the planetary crisis.

At the same time, there is a climate-savvy gold rush beginning, where well-resourced people are looking to buy up the things that will be working and thus valuable in a transapocalyptic world — and get as many of them as they can before people realize how valuable those things are. Think speculative investments in assets like farmland, water rights, rare minerals, fishing rights, and real estate in better-sheltered cities.

Luckily Alex has some ideas for what we should do:

... Ruggedizing ourselves will be a bigger — and no less pressing — task than cutting CO2.

Just catching up is a massive challenge. We must rebuild all the degraded systems around us, work our way out of technical debt and deferred maintenance, and build our way out of the current housing shortage, which is at least hundreds of millions of homes.

We need simultaneously to upgrade that whole process to accomodate our new realities. Engage in climate triage, and abandon all that is untenably brittle. Ruggedize our utilities and transportation grids and cities and everything else to thrive in a much wider range of circumstances than we’re used to expecting. Prepare to accommodate millions of new refugees and welcoming even more internal climate migrants. Speed is justice, and scale is inclusion.

I like this systems perspective:

| ||

| https://twitter.com/Sys_innovation/status/1454393167441272836 |

The Lantern of Liverpool's most interesting cathedral was one of his great works - sad that this sort of work is not recognised more:

|

| https://twitter.com/OpsProf/status/1461974673357479936 |