Notes: energy, local government, open, social enterprises

The other COP was last month:

|

| https://twitter.com/UNBiodiversity/status/1448189233026437120 |

I enjoyed the Talking Politics episode with Jason Bordoff, on the energy transition. The scale of the big changes needed and how challenging it is to see how they could be made quickly - outside the shift in consumer choices side of things - is fascinating. Jason notes that we cut emissions with pandemic lockdowns, but that carbon emissions need to reduce by more than they did in 2020, every year for 10 years. Affordability of energy is a real tension too, as gas and oil necessarily get more expensive.

Microsoft has been striving to go carbon negative; it did an RFP for a huge volume of negative emissions, and found very few indeed met its criteria for good quality removal (Nature article):

First, the supply of solutions capable of removing and storing carbon viably is a tiny proportion of that needed to reach global net-zero emissions by 2050 (which is an anticipated 2–10 gigatonnes of CO2 per year)2. Although Microsoft received 189 proposals offering 154 megatonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) over the coming years, only 55 MtCO2 were available immediately, and a mere 2 MtCO2 met Microsoft’s criteria for high-quality CO2 removal. Stripe’s 47 carbon-removal proposals amounted to 16 MtCO2, but only 0.024 MtCO2 met the company’s requirement that carbon remain sequestered for at least 1,000 years (see ‘Carbon-market snapshot’).

... Second, the scarcity of proposals that met the companies’ criteria reflects a lack of standards and clear definitions.

... Third, systems for accounting for carbon removal do not distinguish between short- and long-term forms of CO2 storage (see ‘Some carbon-removal strategies’). This distorts the market and discourages investments in more-durable solutions.

Who in the UK is most vulnerable to climate change? Thanks to Tim Davies for the pointer to Climate Just.

Tom Forth writes about local government in England.

However we define it, local government in the UK does less and less. In the late 1800s when Britain was at its comparative economic prime, it was the largest part of the state, especially in the great cities. Soon it started to decline.

After the war and with exceptions, especially in Scotland and Northern Ireland, local government corporations were nationalised and then privatised. Gas in 1948 and 1972 before privatisation in 1986. Water in 1973 before privatisation in 1989. Buses in 1968, and 1985. Council housing in 1980 with right to buy. These are just four examples but the overall effect was in all cases the same, local government responsibilities and assets were shifted to central government, who often later chose to privatise them. Local government did less.

More recently, with no municipal corporations left to nationalise and few national corporations left to privatise the method of shifting the role of government from local to central has changed. Academy Schools move power over public education from local government to national government. Free Schools do the same.

Since 2010, what responsibilities and powers local government retained were reduced by funding cuts to local government combined with central government restrictions on their ability to raise tax.

... In the past decade, Central government employment has grown by a million. Local government employment has fallen by a million, even while it copes with a pandemic.

And the story is even more extreme than it looks. Most of what local government employs people to do today is beyond its power. Local government must, by UK central government law, provide social care. This represents over 40% and rising of local government total spending and offers little opportunity for local democratic input.

... What is left to local government control is small.

Bin collections remain a local responsibility and the biggest topic in local government. Voter registration and elections, libraries, parking restrictions, potholes on local roads, cycle lanes, parks, statues, and Christmas lights add to the issues crowding the inboxes of councillors and their officers.

But even in these areas, there is less and less to decide on. ... Restrictions on pavement parking remain a national competence almost everywhere. There are new central laws on statues, consultations about new central laws on parks, and a promise of new nationalised standards for bin collections.

When local government innovates to deliver better services to its citizens, it is often criticised, threatened, and banned from continuing by central government.

Hundreds of central government challenge funds exist to do things that local government can no longer afford, like digitise public services, keep libraries open, or plant flowers in the town square. They all come with conditions attached that reduce local input and shift decisions on prioritisation from local to national government.

Tom goes on to argue that it's no wonder that local government election turnouts are low, as there is so little at stake; but that elected local government is important

Complete central command in England ... would be less nimble, for the same reason as England’s Covid-19 app came out after Ireland’s and Scotland’s. I think it would make us poorer, for the same reason that Europe’s small nations have higher GDP per person. I think it would be less efficient, for the same reason that a national public transport smartcard has failed in the UK while working in Denmark, the Netherlands, and Ireland. I think it would further divide our society and detach people from the places they live.

Wendell Wallach nails the challenges around the hot topic of AI ethics:

Before I outline my approach, let me ask you an honest question: Why are you interested? Are you committed to improving the world? Or do you merely want to get better at using the language of ethics to justify the things you’re doing anyway?

... The problem is not that ethics isn’t discussed – it is. The problem is that many people in tech have become too comfortable with discussing ethics. They think of it as merely being politics by other means.

... I think of ethics as a way of approaching the challenge of navigating uncertainty. When you don’t have the full picture, ethical values can guide how you act.... as a first step, we can try to be humble. We need to understand the extent to which we are so convinced about what we are doing, we block other viewpoints that could enrich our worldview. It’s the difference between a company that genuinely invites and listens to critical voices, and a company that appoints an ethics advisory board that ticks the boxes – gender and geography – but never raises any difficult questions.

... . As a liberal internationalist worldview is generally considered to be virtuous, the argument goes, tech that is developed by companies with liberal internationalist values must surely make the world better. Unfortunately, it isn’t true.

... To embed ethics effectively, the virtues we need to cultivate are different: the awareness of our personal resistance to be open to others, and the courage to invite diverse perspectives into processes of collective decision-making.

Not that you actually need AI:

|

| https://twitter.com/axbom/status/1448877596553498624 |

How does anyone tell what is real? Vox article about this -

|

| https://twitter.com/ChrisDeLeon/status/1450895630226710530 |

Matthew Sun writes for New Public about online community:

Instead of an egalitarian utopia of anonymous sameness, the digital world is hyper-fragmented, with a dizzying multiplicity of trends, memes, and tribes of varying exclusivity. Anyone who has felt isolated by the offline world and its crumbling institutions is usually just a few clicks away from discovering that they’re not as alone as they thought they once were; however niche we think our interests might be, there’s always a subreddit, or YouTube channel, or TikTok hashtag that somehow suits us perfectly. It is likely that as long as society continues to fail to meaningfully include people of color, so too will we navigate the internet to find alternative narratives that affirm us, so too will the tech capitalists surveil us as we do so to classify and target us for profit.

From real estate brokers to tech companies, our desire to find a sense of home has been hijacked by the agents of racial capitalism. As renowned political theorist Cedric Robinson wrote in Black Marxism, the “tendency of European civilization through capitalism was thus not to homogenize but to differentiate — to exaggerate regional, subcultural, and dialectical differences into ‘racial’ ones.” If the internet enlists us in an endless march towards gleaming, new homes, each more beautiful and individually tailored than the last, we should be skeptical. It is too easy, too frictionless to believe that we will all find our perfect communities in an algorithmically curated set of recommendations. I see these as communities of consumption, in which the soothing feeling of a shared identity is hijacked as a tool for maximizing engagement. To be clear, I am not opposed to the flowering of communities organized around identity on digital platforms; I myself have found comfort in the digital milieu of Asian American and other minority creators. But the tech industry’s constant repetition of platitudes about “connection,” “community,” and “engagement” risks forgetting that these words have historical meanings and political implications, too.

... I wonder about what it looks like to move beyond communities of consumption and towards communities of co-liberation in the digital realm. Just as urban ethnic enclaves like Chinatowns, carved out by enclosures of legal and economic segregation, also became sites of collective struggle, mutual aid, and social change, so too might we reappropriate the communities occupying digital platforms designed for profit to instead serve a vision of a more just future. ... And through participating and contributing to them, individuals might find not only a feeling of belonging, but also a newfound sense of agency.

I myself am searching for these communities of co-liberation, online and offline. But perhaps it is not enough simply to search, to take for granted that they already exist, waiting to be discovered by the perfect permutation of keywords entered into Google. Instead, to orient myself homeward, I must also orient myself towards an attitude of active construction, rather than simply passive consumption. The idealized communities we yearn for will not simply be found through freedom of movement on the internet and ever-improving algorithmic curation. Instead, our collective imagination must serve as the blueprint to build them.

We seem to be hoping for a lot from data and yet... it's messy:

|

| https://twitter.com/realhamed/status/1451849140640665605 |

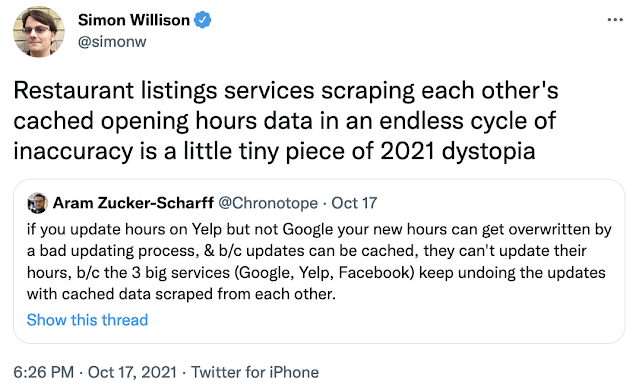

really messy:

|

| https://twitter.com/simonw/status/1449789042950770695 |

There's also this great thread from Matthew Somerville which notes numerous ways that Google's search results are getting worse, rather than better, as AI is applied. My favourite:

And all too often we already know what to do. Does the data really help?

|

| https://twitter.com/Floppy/status/1441316704299012104 |

Worryingly, though, people still want to trust computers, even in the most critical cases (this FOI request didn't uncover the information and hopefully other inquiry will find out what happened here):

|

| https://twitter.com/sjmurdoch/status/1446516214663192588 |

Michael Weinberg writes about the next wave of open.

...the fundamental nature of the most important debates around openness appear to be changing.

A number of different open communities - open software and hardware, open culture, open data, open GLAMs, etc. - seem to be entering a new phase of their development. This new phase is characterized by their successful growth into and adoption by the mainstream.

This new phase comes with new debates. In the early days of openness advocacy, the core debate involved a small group of people working to defend the very concept of openness to a skeptical world. This debate played out between openness advocates within the community and openness skeptics outside of the community. It was about the fundamental legitimacy of the concept of openness.

... While debates about the fundamental legitimacy of openness continue (and will continue), the growth and success of openness has given open communities confidence that the core concept of ‘open’ is viable. This has helped shift the discussion around openness in new directions towards new questions. The key debates in openness advocacy now involve a larger group of people trying to reconcile openness with other values that they hold to be equally dear.

Today’s debates are shaped by two related factors: first, that openness is no longer fighting to prove its fundamental legitimacy; and second, that the openness community is now big enough to include people who view openness as one of many important values. The openness community is now larger than its original ‘single issue voters’.

How communities adapt to these conversations, or whether they stick to the doctrinaire approach of the early days, will be interesting to see. I remember suggesting many years ago to open data people that the popular slogan "open by default" might be a scary prospect to those for whom 'government data' tended to mean personal information about themselves, and being told that no one could possibly think that. The 'ethical open source' folks are driving a more thoughtful discourse, which is great.

There's also a terrific amusing thread -

|

| https://twitter.com/luis_in_brief/status/1441060428642078732 |

Belinda Bell, who knows the social enterprise space extremely well, is reflective. Has the idea of using capitalist ideas to deliver social justice failed?

I have had the privilege to teach, support and work directly with thousands of dedicated, committed, bright and bold social entrepreneurs. And now, looking back, what has been achieved by their enterprises, my own, and the sector as a whole? Very much less than I had hoped. And I have come to think that, actually, we have even done harm.

...There has been precipitous growth in ventures identifying as social enterprises. A database search from sources including mainstream newspapers, journals and broadcast transcripts shows mentions of social enterprise growing from fewer than 100 per year in 2000 to over 10,000 every year since 2014. ...

And yet the question of distribution of profit goes to the heart of the radical endeavour that social enterprise represents. ...Some social enterprises extract profits for private gain; this enables social enterprise thinking to permeate the mainstream, but also allows uncertainty to enter, creating a lack of clarity about the underlying ethos of the sector. It opens the door for ‘social washing’ of regular businesses.

Belinda goes on to detail two different ways that social enterprises can fail to sustain and deliver positive impact - and notes that

Importantly, both organisations are failing to explicitly critique the systems within which they work. They are trying to apply a business solution to a social problem, but they are not looking at the root causes of the problem.

... We must challenge the presumption that scale is inherently positive in any organisation – regular business, social enterprise or charity.

And then there is impact investing. Any critique of the social enterprise sector reaches its apogee in this arena. The topic deserves a full airing in its own right, but, in summary, those who seek social equity should question the process that leads to such uneven distribution of resources that a class of investors exists in the first place. And we need to face up to the fact that the underlying facilitating condition – a growth economy – is unsustainable for the planet.... I draw some hope from the fringes of the movement; a pocket of activity in which there may be an antidote to the anomie and isolation of modern commerce. ... But, for the most part, social enterprise has been unable to demonstrate that it is really possible to make more things count in capitalism than just the bottom line. To be truly radical it is necessary to go to the root causes of things. Those involved in social enterprise – funders, practitioners, policymakers –should perhaps refocus on the systems and context and consider how that broader environment can be adapted, improved or dismantled. For me, it is time to go back to the drawing board.

|

| https://twitter.com/JanGold_/status/1445712006229606401/photo/1 |

There's 49 thousand miles of footpaths in England and Wales that could be lost if they aren't documented and applications made to register them. The paths were found through a big crowdsourcing project. Good stuff.

Online forums are closing, with communities moving to Discord or Facebook or whatever. Luke Plunkett notes some of the loss - no long term record, no searching for helpful tips, a very different kind of interaction. HT Adrian Hon, who tweets that running a Discord instead of a forum for a previous project would be high energy but exhausting. The information on DIscord, Facebook groups, and so on, is entirely hidden from those outside the group - there's no way to find the content or the community. This is indeed a big loss compared to when you could, say, search the web for advice on an obscure problem with your car, and find not just advice but a group of people who cared and could help.

I listened to the audiobook of Climate Change and the Nation State by Anatol Lieven. It was interesting to get a perspective on how the military might be interested in reducing climate change (not just addressing the effects of it with migration and security matters). It was perhaps a little over optimistic about replacement of jobs with automation, compared to what seems possible to me. It was challenging to a progressive viewpoint, with the idea that some progressive ideals are luxuries, OK for luxury times but perhaps not the times coming. To make action possible we need to avoid extreme division, so maybe some progressive values need to be set aside to focus on shared values that could drive emissions reduction and other changes.

The UK's 150 page government inquiry into pandemic handling doesn't mention ventilation or air flow (This thread), and has only one mention of face coverings or masks. A Nature paper from a year ago talks about long distance virus dispersal via HVAC systems.

I tried to keep on top of the sewage-discharge debate but missed a lot of the complexity - FullFact highlights some of it. How does anyone ever feel they have enough information to have a considered opinion on anything outside their specialist subject these days?

Ruth Ben-Ghiat says we should play, even though there's also so much to do: "Yes, we have a democratic emergency on our hands, and much work to do. But we need to play anyway, for in playing we affirm our humanity, and our humanity is what autocrats fear." Step back from the fray and pause, sure, but also consider playing.