Notes: fresh air, suppliers, local communities, stories

Great contributions from Cofarm board colleague Sue Pritchard, and Maintain friend David Edgerton, on the Briefing Room on global supply chains.

There was an interesting highlight for me in Talking Politics with Michael Lewis about his pandemic book, about when demand for nose swabs became very high, the price went up, factories ramped up production - not just of nose swabs, but of fake nose swabs. Astounding.

|

| https://twitter.com/sarahmanavis/status/1397517661299425280 |

There's still a lot more sanitiser stations than open doors or windows in town, even on the warm, dry days.

|

| https://twitter.com/linseymarr/status/1392906073804259341 |

It would be nice if you could tell what venues had better ventilation.

|

| https://twitter.com/kenhorn/status/1397083171720765444 |

The Prepared Slack community had a discussion about repair cafes and unpaid labour. Volunteering in these contexts is hardly aligned with ideas of valuing repair work (although in some cases those with the greatest need to repair goods may be unable to pay). The Repair Cafe Foundation requires that repairers are unpaid. Tool Libraries often follow a similar model; and an overt anti-capitalist position might reject paid work like this. Are there other viable models that pay a fair wage to repairers, and support free or discount repairs for those in need?

iFixit tell the sad tale of Samsung's upcycling programme - a great vision and a worse than useless reality. Is this upcycling washing?

|

| https://twitter.com/randal_olson/status/1383410748978712577 |

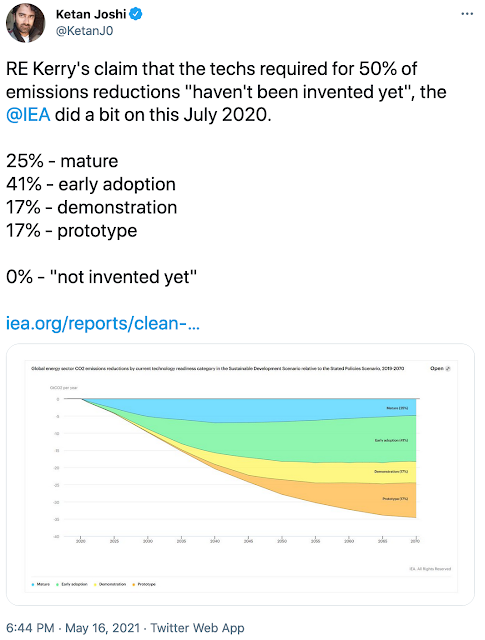

Technology is probably not the answer:

|

| https://twitter.com/KetanJ0/status/1393985805035704328 |

Sym Roe has an insightful thread about What3Words - "it's trying to solve a problem that many people can understand quickly. They've done an incredible marketing job and taken a closed approach, and no one really cares because the problem is real, or at least easy to imagine."

|

| https://twitter.com/EthanZ/status/1391800159605084162 |

Google Docs is switching from using the standard, accessible and flexible Document Object Model, which is designed for documents, to Canvas rendering, which is designed for images, making web documents more opaque [thread].

The European Parliament is not impressed by the lack of enforcement activity at the UK Information Commissioner's Office. The Open Rights Group is raising money to take the ICO to court to get laws around online advertising enforced. HT Michael Veale.

Interesting point that we should maybe focus on institutions rather than the tools they use, as it's very hard to disconnect entirely from big power, whether tech business or state:

|

| https://twitter.com/j2bryson/status/1401771749361000449 |

Steven Murdoch writes about the Post Office Horizon case - alongside other issues, he notes:

Organisations might not have the information they need to show whether their computer systems are reliable or not (and may even choose not to collect it, in case it discredits their position). The information might be expensive to assemble, and so they might argue it is not justifiable to disclose. In some cases, publicly revealing details about the functioning of a system could assist criminals, so it gives organisation yet another reason (or excuse) to not disclose relevant information. For all these reasons, there will be resistance to a change in the presumption that computers operate correctly.

I believe that we need a new way to build systems that need to produce information to help resolve high-stakes disputes: evidence-critical systems. The analogy to safety-critical systems is deliberate – a malfunction of a safety-critical system can lead to serious harm to individuals or equipment. The failure of an evidence-critical system to produce accurate and interpretable information that can be disclosed could lead to the loss of significant sums of money or an individual’s liberty. Well designed evidence-critical systems can cost-effectively resolve disputes quickly and with confidence, removing the impediments to disclosure, allowing a change in the presumption that computers are operating correctly.

We already know how to build safety-critical systems, but doing so is expensive, and it would not be realistic to apply these standards to all systems. The good news is that evidence-critical engineering is easier than safety-critical engineering in several important ways. While a safety-critical system must continue working, an evidence-critical system can stop when an error is detected. Safety-critical systems must also meet tight response-time requirements, whereas an evidence-critical system can involve manual interpretation to resolve difficult situations. Also, only some parts of a system will be critical for resolving disputes; other parts of the system can be left unchanged. Evidence-critical systems do, however, need to work even when some individuals are acting maliciously, unlike many safety-critical systems.

|

| https://twitter.com/PeteApps/status/1387323172593094656 |

This had echoes, for me, of the discourse around development (in the context of international aid, not software, because every word has confusingly disparate meanings when you work in different sectors):

|

| https://twitter.com/radiocatherine/status/1397521681510539264 |

Worth reading the whole article by Jessica Prendergrast - I appreciated the points about different scales/boundaries of local communities, and the importance of commercial players within communities (pubs, small shops, etc).

The simplest intervention as others, Haldane included, have mooted, is investment in social (and cultural which is just as important though it barely gets mentioned) infrastructure. To make any in-roads, it is critical that this is not watered down to mean basically anything that is not physical infrastructure. The focus must be on places, organisations and practices that encourage, embed and broaden attachments. This can include all kinds of places from post-offices, pubs, shops, community centres, art galleries, parks, and it can include much of the public sector — nurseries, schools, hospitals, — but these are all only social infrastructure if they build opportunities for associational life. Schools, for example, are often entirely detached from community life, hospitals too; and pubs can be the most exclusionary of all places. It’s not a catch-all. The practice matters.

... Where local government is embracing its role as enabler and partner in community economic development — cities like Plymouth, Liverpool, Bristol — we see real impact, and a key role in supporting two things which communities tend to lack — an ability to underwrite risk and access to finance. Notwithstanding the debate about whether to substantially re-resource local government, it is vital therefore that no revival of local government’s standing should be used, intentionally or otherwise, as a mechanism by which to flatten the seedlings of the emergent ‘fourth sector’ of purpose-driven, often community-led, organisational forms. This requires a genuine culture shift in local government and a genuine acknowledgement by politicians on all sides that if the ambition is to reconnect with all those not obviously benefiting from the prevailing system then communities are not just conveniently placed, but better suited, to delivering meaningful change in economic agency.

... it is important to recognise that these efforts at community enterprise are not seen by sector leaders as only a symbiotic solution to market failures in the current free or pro-market, neoliberal system but instead as a demonstrable way to replace it with something different. These leaders are grappling with the major social ills of our time — from social fragmentation to environmental pressures to economic restructuring and global volatility. They want to be a part of building a new, better future, within an economic settlement that prizes social, human or environmental value over financial value or which disputes the organising principle of profit. They do so by incorporating attachment in some form into their business models and are committed to economic priorities being decided and owned locally, at scales adapted to suit place-based attachments.On a local level, Athene Donald writes about what levelling up might mean in/around Cambridge, the most unequal city in the UK, and with areas of poverty to the East and North, as well as the Western route to Oxford, which is so much discussed in research terms.

At CoFarm we're doing a fundraiser - over 200 volunteers together grew over 4.5 tonnes of fresh local produce for 8 community food hubs last year, and we want to double it this year. Donating the produce is great for those locally living with food insecurity, but not so great for covering expenses!

There have been positive signs that the government might include get binding targets about nature and biodiversity in the Environment Bill. Still probably worth signing this petition from a coalition of UK wildlife groups if you care about this.

The UK is going to require pension fund trustees to monitor and report on how climate risks may affect their investments.

Alex Steffen on the pace of climate response:

When we do get around to having sober conversations about the magnitude of the changes tearing through the world around us, most of the ideas we discuss are decades past their sell-by date, and treat the crisis as a distant problem. Acting on behalf of our grandchildren. Gradual policy changes. Slowly rising carbon taxes. Eventual improvements in technology. Living “a little more sustainably.” Planting trees. Planning to build some sea walls.

If the Biden moment feels to many like a headlong rush forward it is because of this context of silence and gradualism.

... We’re winning too slowly because we face a set of interest groups for whom losing slowly is the same thing as victory.

We live within what I call the Interval of Predatory Delay, a time that began over 50 years ago, when a set of high-polluting industries decided it was wiser and more profitable to fight to delay change on climate and sustainability than to invest in lower-carbon and more sustainable systems and processes. Easier to torch the planet and lie relentlessly, they decided, than avoid catastrophe and lose revenue.

For decades now, they have been controlling the pace of their own defeat. They have spent billions of dollars denying the science, downplaying the consequences of inaction, inflating estimates of the costs of change, sabotaging our civic debates about the future, bribing and buying public leaders and attacking the reputations and livelihoods of thousands of scientists, journalists and advocates who’ve pushed for a greater sense of urgency.

A very real example of this from the recent Cumbrian coal mine planning question, in a great long read from Rebecca Willis:

The councillors were being besieged by these discourses of delay, complicating what should have been a simple decision. Emissions from burning the coal don’t count, they were told; just one extra coalmine won’t make any difference; coal is needed to make the steel for wind turbines … These arguments worked because they provided cover to councillors desperate to approve a project that promised jobs. As the local candidate opposing the mine put it, some supporters “really understand the argument about climate change, but think, as we all tend to do, that this is just one exception that we could let through, because this place really needs it”.

The need for jobs in the area seemed to drive folks adopting any kind of story that offered actual jobs soon, even if it was otherwise worrying, and making that as positive as they could in the stories they went on to tell.

Phoebe Tickell writes about how important stories are to human existence. But:

I believe that we are in a period of story breakdown, an era that my teacher and mentor, Joanna Macy refers to as ‘The Great Unravelling’. As many stories that we held so dear in our near-recent human history are unravelling, the rates of mental health problems are rising. Things like “if I spend my life working hard everyday then I will be financially secure and happy,” or “if I go to a good University I will be successful” are no longer a given. Many young people feel they have no way of predicting what the future holds for them because many of the jobs that we do today didn’t even exist when we were at school.

Other stories which are starting to breakdown revolve around broader societal assumptions. “All technology is good, and the more technology we develop, the more our society advances” or “bottled water is better for you”. These widely accepted stories don’t make sense anymore when you take into account the mountains of electronic waste in Ghana, or the levels of plastic in our oceans. Despite this, the old (but not ancient) stories continue to live on and on in our collective imagination.

We’re in a chasm between stories that used to function and new stories which haven’t yet gathered enough coherence to function effectively. We can respect the stories of the past, but we also realise that they often aren’t actually helping us to navigate the reality we are living in anymore.

I think there was something good in Matthew Taylor's short video, but the drawings distracted me. Maybe listen to the audio only.