Weeknotes: populism of equal cheating, warranties, language

Thanks Adrian McEwen for the link to this clear depressing summary of UK government failures over 12months by Michael Head.

|

| https://twitter.com/JolyonMaugham/status/1355533287482138626 |

I remember the energy and drive when the UK hosted the Open Government Partnership in London in 2013, but we've not kept up:

|

| https://twitter.com/TimJHughes/status/1358433586848821248 |

Where should the UK invest in R&D? Tom Forth writes about R&D, transport, skills and growth.

Check out the amazing talks from Wuthering Bytes 2019, now on YouTube. It was, as ever, an honour to compere these incredible sessions. I shouldn't pick favourites, but Sarah Angliss on atomic gardening and Georgina Ferry on Lyons cafes and the first business computer were highlights for me.

I loved (ha) the thoughts in this thread of Chiara Acu's art - "in the spirit of waging love." Many thanks to Cassie Robinson for sharing these this morning :)

There are so many good bits in Matt Stoller's latest newsletter. Highlights mine:

And this brings me to the Cantillon Effect, in which how money travels matters for distributional purposes. There are an endless number of corrupt bailouts and scams that all of us have seen over the past fifteen years, from the financial crisis to bondholders destroying Puerto Rico and Argentina, to the ‘flash crash’ of 2010, to the CARES Act bailout in the spring, which boosted the fortunes of billionaires once again. One of the key reasons for why these bailouts always seem to tilt to the powerful is because that’s how our financial plumbing is set up - the pipes from the Fed to big banks work quite well, those from the Fed to small businesses don’t.-- Matt calls this the "populism of equal cheating"

... Most of the retail investors betting on GameStop are going to lose their money, and Wall Street is going to be fine. People on Reddit - some of whom are probably professional insiders - are helping men like Donald Foss, who owns a half a billion dollars of GameStop; Foss is a billionaire who made his money from subprime auto lending, the sleaziest business imaginable...

In fact, much of what Robinhood is now doing shouldn’t be allowed, including encouraging retail clients to be speculating in margin accounts and in options. And my guess is that there are big funds with anonymous people on the subreddit whipping up a furor - pump and dumps on message boards didn’t start in 2021. Ironically, I don’t think they those on WallStreetBets would disagree, I think they would just claim that if you’re going to put a stop to gambling, stop it on Wall Street first. And that’s right, the amount of leverage and/or cheating by hedge funds, big banks, private equity firms, and market-makers like Citadel is likely off the charts.

... The basic problem that GameStop is revealing in our economy writ large is that as a society, we are increasingly putting our time, energy, capital and talent we could use to build fun or useful things into gambling or acquiring market power.

Onto supply chains:

.... A few weeks ago, I talked to a contact in the domestic textile industry, who told me that when the pandemic hit, most companies in that commercial area turned to producing personal protective equipment for government stockpiles. And now we have a domestic supply chain that can meet our own needs for things like N95 masks, which was not true at the beginning of the pandemic. Only, she noted, there’s a problem. The big buyers who represent most hospital purchasing still want to buy from China, even if individual hospitals might want a more reliable domestic producer.I hadn't thought of these purchasing choices as being particular related to finance.

Without action against these buying monopolies and tariffs to stop China from dumping into our markets, these new supply chain will die. This isn’t isolated to textiles, but is a long-standing economy-wide bias towards monopolies and finance and against production of real goods and services. With the current setup of our markets, there’s just no clear reason to be investing in useful enterprise.

Very low or negative interest rates mean that investors can’t find any place to place their savings. Investors perceive there are no more factories to build, no distribution centers to create, no new energy systems to research, no more products to create. You can only stuff money under a mattress, and the price of mattresses is going up. Our financial system, in other words, is acting like we have no more social problems to profitably solve.Matt also notes that responding to this doesn't go down well:

What is really happening is not that we’ve run out of problems to solve, but that the economy has become a giant “kill zone,” which is a term venture capitalists use to describe areas they can’t invest for fear that a monopolist will crush their company. ...

With an economy of monopolies, there are now large profits with nowhere to go because investment in new production doesn’t make sense if you have market power. Workers have little bargaining power, so the extra money doesn’t go to them. Taxes on capital are low, so the money isn’t heading back to the government. Moreover, a lot of small businesses have been shut down because of the pandemic, so people can’t put their savings into new business even if they wanted to. Monopolies and a corrupted financial system have broken the ability to put money into useful enterprises. So where is it going?

Speculation.

....Most of the politicians speaking out about Robinhood, however, adopted a bizarro populist approach to the speculative fervor. Instead of saying let’s get money into the real economy so it reaches everyone in productive ways, they argue that everyone should have the right to cheat. The one exception is Elizabeth Warren, who made the case that the very speculation itself was dangerous. She asserted that “Casino-like swings in stock prices of GameStop reflect wild levels of speculation that don’t help GameStop’s workers or customers and could lead to market instability,” and demanded that the Securities and Exchange Commission investigate speculators on both sides, and the middlemen.

It was weird to point out, as Warren did, that GameStop has workers and customers. And the pushback online towards Warren was intense, even among her own side. She’s clearly correct, and yet, there’s a reason that it’s very hard to argue for financial regulation in an economy that is incredibly concentrated and unfair, and speculation is one of the few avenues open to a large group of people. Cynicism is the order of the day, at least on the internet.

|

| https://twitter.com/matlock/status/1360242963490742276 |

|

| https://twitter.com/suepritch/status/1357267001241124865 |

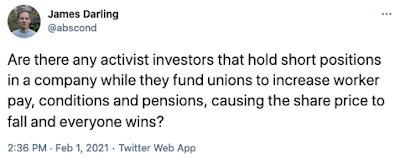

Creative idea:

|

| https://twitter.com/abscond/status/1356250122540216321 |

Thanks to Anish Mohammed for the link to this fascinating article by Holger Mack and Tom Schroer about security's midlife crisis.

The classic application software stack relied, at all levels, on a development approach that was largely based on homegrown software developed by (often large) companies that had their own developers. ...The best practice was to integrate security into the lifecycle as early as possible.

Measures such as developer training, threat modeling, and security planning aim at creating security by design and proactively prevent design flaws and bugs. Security testing, code reviews, and so on additionally detect any mistakes made during development; security response processes have the goal to provide fixes quickly, if necessary.... In the modern stack, coding that follows such a development process is increasingly reduced to only a small set of “glue code” or configurations built to combine software developed elsewhere, especially in the open source community. ...

... the increased scale of today’s challenge becomes more apparent when you look at other aspects of the modern architecture, such as:

- The size and complexity of projects: Kubernetes (including Docker) as well as Cloud Foundry and Hadoop consist of millions of lines of code and are themselves built by combining other components, which, again, consist of more open source projects.

- The increasingly dynamic nature of today’s architectures: Those architectures are built on the principle of dynamically loading components and dependencies from their source (e.g., using NPM). What, at first glance, looks like a good security measure (always use the newest version) becomes, with more insight, a security challenge, especially if the source and its controller are unclear. ...

- Rapid replacement: Last but not least, technologies are superseded by newer and cooler versions at an amazing rate. This leaves very little time to develop the right expertise on how to secure them. The Hadoop project is just one example of such a complex technology trend, with a fast-growing ecosystem of related components and subprojects (Ambari, Cassandra, Pig, and Spark).

Technology takes work. Great thread from Dan Hon:

|

| https://twitter.com/hondanhon/status/1359587806159405057 |

Somehow I'd missed this 2019 article from Sean McDonald on how warranties could transform digital products.

So, warranties don’t just create liability, they focus it: warrantied products face specific liability, whereas products without a warranty face broad, less predictable liability.

Warranties do two critical things. First, they require a manufacturer to specify how and where its product should be used and to run tests to ensure it performs under these conditions. And second, warranties attach liability to the risks created by a product to the user. Warranties are familiar enough to seem trivial, but they are an important part of how we structure the responsibility for the things we create, share and sell — including intangible and digital products.

In analog products, warranties are often regarded as badges of quality; companies that are willing to guarantee their products are seen as more reliable than those that do not. Those guarantees didn’t come to be for marketing’s sake alone. Companies, especially those working on products with significant or potentially dangerous impacts, would go through the effort of defining and testing not only whether a product worked but what conditions it worked in and how it worked in different use cases. In short, to offer a warranty, companies needed to do extensive contextual research and development before launching the product at all.

|

| https://twitter.com/thornet/status/1359132821365936130 |

Debbie Cameron on sexism in language around sexual anatomy, highlighted by a cancer prevention campaign, of all things.

|

| https://twitter.com/AlexSteffen/status/1355788370572582913 |

The best thread of thoughts I've seen on ethical licences and open source, from Luis Villa.

|

| https://twitter.com/matthewstoller/status/1358486111409082368 |

McSweeney's on form as ever with Simon Henrique's artist's statement on the design of a restaurant's outdoor seating space.