Fortnightnotes: time horizons, unseen infrastructures, toilet paper

Thanks Peter Bihr for picking out this from the Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson:

The tragedy of the time horizon:The infrastructures we don't pay attention to:

“Having debunked the tragedy of the commons, they now were trying to direct our attention to what they called the tragedy of the time horizon. Meaning we can’t imagine the suffering of the people of the future, so nothing much gets done on their behalf. (…) What we do now creates damage that hits decades later, so we don’t charge ourselves for it, and the standard approach has been that future generations will be richer and stronger than us, and they’ll find solutions to their problems. But by the time they get here, these problems will have become too big to solve. That’s the tragedy of the time horizon, that we don’t look more than a few years ahead”

|

| https://twitter.com/seanmmcdonald/status/1315622673888743424 |

Eli Pariser on online public parks:

Venture-backed platforms make poor quasi-public spaces for three reasons.

First, as the legendary venture capitalist Paul Graham put it, “startups = growth.” The focus on growth—of users, of time spent, and then of revenue—is the defining trait that has made Facebook a $750 billion company. And the key to rapid growth is optimization to create a “frictionless” experience: The more relevant the content you see, the likelier you are to click, return to Facebook, and bring your friends.

But friction is essential to public space. Public spaces are so generative precisely because we run into people we’d normally avoid, encounter events we’d never expect, and have to negotiate with other groups that have their own needs. The social connections that run-ins create, social scientists tell us, are critical in binding communities together across lines of difference. Building a healthy community requires the careful generation of this thick web of social ties. Rapid growth can quickly overwhelm and destroy it—as anyone who has lived in a gentrifying neighborhood knows.

... The third and biggest problem with private ownership of quasi-public space is that public spaces require constant, active care and maintenance by skillful stewards. Scholars like Sarah Roberts have pointed out that the nuanced labor of governance and maintenance—finding the balance between welcoming everyone and providing safety and comfort for everyone—is critical to the health of online communities.

... But while this work is essential, it’s also both undervalued and costly. As the Maintainers have argued, building shiny new edifices tends to be seen as a masculine pursuit and lionized, whereas the work needed to keep spaces functional and livable over time is often seen as boring, feminine, and, as a result, uncompensated and sidelined. The cost of this labor also doesn’t scale the way techies like; the more people in a space, the more labor is required, and the greater the expense.

Private spaces and businesses are critical for a flourishing digital life, just as cafés, bars, and bookstores are critical for a flourishing urban life. But no communities have ever survived and grown with private entities alone. Just as bookstores will never serve all the same community needs as a public library branch, it’s unreasonable to expect for-profit corporations built with “addressable markets” in mind to accommodate every digital need.

Bryce Roberts made me laugh -

I assure you there are founders out raising money right now in the hopes of building a business so they can flip it, make millions, and fund their own comfortable “post financial” lifestyle. Of course, they would never frame it that way; so let’s be clear, if your pitch deck has an “exit strategy” slide you are pitching a lifestyle business.

Terrific thread from Ingrid Burrington about what 'digital infrastructure' seems to mean to the philanthropic funding community:

|

| https://twitter.com/lifewinning/status/1318587084396003329 |

From Deb Chachra's newsletter - highlight mine:

6. don't have to give up capitalism but...: Even leaving aside the moral issues around provision for human survival needs, infrastructural systems don't fit neatly into a market-based model, given network effects, natural monopolies, positive externalities, and more. That last is the term for when a person benefits from something a company does without paying for it, but I haven't been able to figure out what it's called when corporations benefit from what society pays for without contributing to it in their turn. Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing's phrase 'salvage capitalism' (from The Mushroom at the End of the World) gets at the idea, but it suggests that it's something that happens at the edges, rather than being utterly, not to mention increasingly, central.

|

| https://twitter.com/iotwatch/status/1317778504663130112 |

Patrick Meier writes about the structural blockers to global South activities and collaborations and shifting power:

A multinational company that believes in the Power of Local wants to hire an African Flying Labs for a local data acquisition and processing project (precisely the kind of opportunities we seek to transfer to local experts as part of our shift the power strategy). Parts of the contract includes a list of compliance needs required by the client. One of them is “Third Party Drone Insurance” for an amount of US $1 million. While this is standard for North American or European drone service providers, such insurance does not exist in many African countries. And if they do, local coverage is often limited to much smaller amounts, e.g., TSH 10 million in Tanzania (equivalent to roughly US $4,300), an amount adapted to the local economy and needs. The contract can only be signed once all the client’s compliance needs are met (and ticked off in the vendor system by having a copy of the valid insurance contract), which neither the client’s project team nor the Flying Labs team has power over. What to do?That's just one example from Patrick's article. It's super hard to centre local communities when global structures of travel, finance and legal structures are designed otherwise.

Tales of radioactive sand - the impact of extractive industry, by Stephanie Postar (via Justin Pickard).

After hearing that several villagers stored bags full of radioactive sand inside their family houses, the nuclear scientist explained that he went into a man’s home with a Geiger Counter. Moving through the house, closer to the bag of sand, he recounted how changes in the quality of the sound corresponded to an increasing presence of radiation. He knew that the people in this village, which is located close to Tanzania’s first uranium mine, kept the bags in their homes because they did not want to give away something that they knew was valuable, like gold or the gemstones mined in the area.

|

| https://twitter.com/CarolineLucas/status/1315755708919541761 |

CoFarm board colleague Sue Pritchard writes in the Guardian:

In a world of polarised debates, there is a broad, non-partisan consensus on the issue of trade and standards. So it was disappointing – even if predictable – that the government whipped against amendments to protect UK food standards in the agriculture bill, which returned to the House of Commons this week. The key amendment was defeated last night by 332 votes to 279. Curiously, many Tory shire MPs voted against the expressed concerns of their farming constituencies, while Ed Davey and Keir Starmer donned their wellies and backed British farming. Farming minister Victoria Prentis argued that the amendments were not needed, since the government had already promised to uphold UK standards in future trade deals.

... Let’s be clear: trade is a good thing. It gives us choices and flexibility. It builds reciprocal relationships between countries, for a more stable and secure world. We can import what we don’t produce at home; countries can specialise in those things that grow better in their climate or conditions; and we can offset risk, if our own production fails – a point relevant for UK wheat markets, after floods and droughts over the last 12 months affected our own production. But it also has downsides. The kind of buccaneering free trade anticipated by the likes of Liz Truss is about handing over more power to the markets to drive down costs, producing cheaper goods and a greater range of options. This might be great for certain businesses and those that invest in them. But when the cost of production falls too low, someone, somewhere, pays.

... Most businesses want a level playing field of globally agreed, simple and rising standards that helps them play their part in tackling the climate and nature crisis. What do British citizens want? The Climate Assembly report published last month demonstrated that – with the right information and evidence – citizens want a fair, transparent and sustainable food system. The public consistently say they do not want to compromise on food standards – they are outraged that poor and vulnerable people are most at risk of diet-related illnesses, and the most unhealthy and ultra-processed foods, made from cheap commodities, are promoted most aggressively. Proposals to improve labelling alone will not do. Governments must put legislation in place to uphold safe and secure standards, to act on the climate and nature crisis and improve public health and wellbeing.

Sue's organisation, the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission, also have a helpful fact sheet about the WTO. I was delighted to learn of the Codex Alimentarius Commission. What a name.

The Festival of Maintenance isn't hosting a Festival this year, so we decided to refresh who we are a bit, for our new focus on community (we've opened up our Slack) and online events:

I really enjoyed two podcasts this fortnight - Fintan O'Toole on Brexit and the revolutionary mentality (Politics on the couch), and Talking Politics about cronyism, with my Trust&Technology colleague Jennifer Cobbe. Jennifer also writes in the Guardian about Facebook as a threat to democracy.

I appreciated the questions raised in this thread, which I spotted thanks to Lilian Edwards:

https://twitter.com/jelenajansson/status/1298118830976360449

AccessNow have resigned from the Partnership on AI. Having been fairly involved in this when I was working at Doteveryone, I'm not entirely surprised - the civil society interaction side was not really thought through then and I don't think that's changed much if at all.

Some tiny bits of data from work that took time from me through the middle of the year: University of Cambridge SARS-CoV-2 testing info.

The Open Source Hardware Association "weather report" is out, highlighting both the success of the last ten years of open hardware, and also some of the questions which remain.

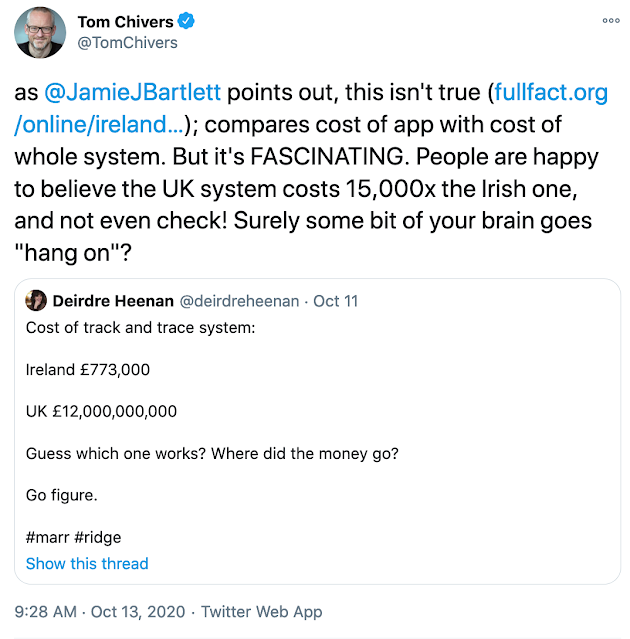

Checking is sadly uncool compared to sharing drama:

|

| https://twitter.com/TomChivers/status/1315932410127757312 |

But then what difference do facts make?

|

| https://twitter.com/mrchrisadams/status/1316630354082623488 |

Rachel Coldicutt has written a nice briefing note which should help civil society groups respond to the National Data Strategy consultation. It's good to have helpful guides like this and encouragement for groups who don't think they are into 'digital' to be able to have a voice.

Shoshi Parks writes about toilet paper, and alternatives:

For his 2017 book, Bum Fodder: An Absorbing History of Toilet Paper, Richard Smyth went deep into the bowels of toilet-paper history,

... You think the golden age of toilet paper may now be coming to an end based on a variety of factors, one of which is environmental. Does what’s happening with the coronavirus right now change your prediction at all?

... I don’t know. I would hope that people start to realize we’re cutting down mature forests to make paper that we’re gonna wipe shit on. Is this sustainable? And you’d hope it would be one of those industries that would feel pressure in that direction.

But another problem is that people don’t want to talk about it. And when people don’t want to talk about it, it’s quite difficult to effect change. It’s heroic work—particularly in the developing world, where people have to be genuinely brave to speak out [on issues of personal hygiene and waste]. This whole toilet business needs a revolution. But that’s a tough revolution to lead.