Weeknotes: climate, crises, citizen's assemblies, conglomerates, universal credit

Infrastructure as cyborg collective. Deb Chachra writes in her newsletter:

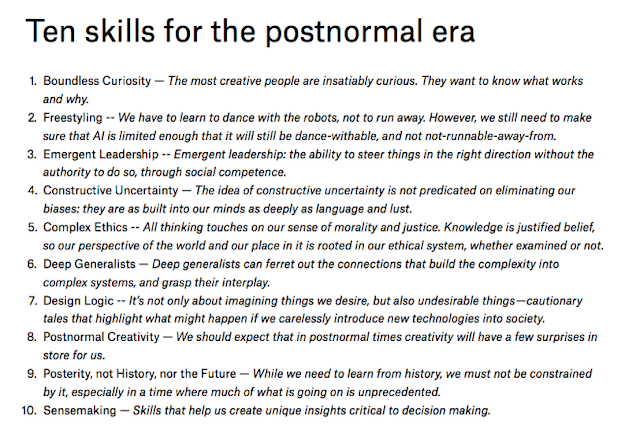

Thanks to Phoebe Tickell for sharing Eirini Malliaraki's tweet about "ten skills for the postnormal era." Whilst it is a bit of a word salad in parts, as a commenter noted, some bits resonated with me: deep generalist in particular. Perhaps that's me.

WeClock is a worker empowerment app, which enables people to track their work activities and issues privately and review them.

New research on data challenges in social care (HT Lydia Nicholas)

The Open Repair Alliance continues to collect information about people repairing things.

Mmhmm - intro video via Justin Pickard who says 'Pitching itself as the go-to for “people who want to stream PowerPoint instead of Fortnite.”' Looks like it might be a useful tool. My other exciting online chat tool learning this week was from Roland Harwood, who uses a video of a countdown clock as his Zoom backdrop, so everyone can see how long the current speaker has to go.

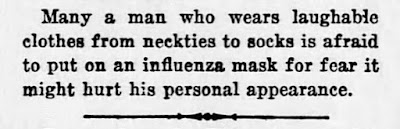

Not only is this an amusing vintage line, it's also authentically vintage. You can't rely on that with viral internet stuff, but Terence Eden checked it out so we don't have to.

Amazing clouds in Belfast:

The infrastructure researcher and science fiction writer Paul Graham Raven has offered up a surprising and insightful way of thinking about our infrastructural systems: he describes them as making us a 'cyborg collective'. Not an individual cyborg, in the 'Ellen Ripley operating a power loader' sense, and not a collective of individual cyborgs, but a single cyborg collective:

Infrastructures are a sort of tool: they’re a prosthesis, an extension of baseline human abilities. … But it’s not just you that’s dependent on infrastructure, the way an earlier you was dependent on being able to knap flint and whittle bone. No - you’re dependent on infrastructure as a community. The prostheses upon which your life now depends are augmentations not of your own body, but of the collective body of your tribe or village.

... Alone in my apartment, at dusk, I flip a switch to turn on a light. In that instant, not only are my individual senses augmented (now I can see at night), but I become part of a continent-spanning colossus. My reach extends out for thousands of miles, across a national border, encompassing a nuclear power plant, a massive hydroelectric project, scores of substations, thousands of pylons, and an incalculable amount of human expertise, skill, and labour. As an individual, I only call on the tiniest sliver of everything this system produces, but it couldn’t exist were it not collective.

Thanks to Phoebe Tickell for sharing Eirini Malliaraki's tweet about "ten skills for the postnormal era." Whilst it is a bit of a word salad in parts, as a commenter noted, some bits resonated with me: deep generalist in particular. Perhaps that's me.

|

| https://twitter.com/irinimalliaraki/status/1280422535394287616/photo/1 |

WeClock is a worker empowerment app, which enables people to track their work activities and issues privately and review them.

We set out to ask how we can use new, emerging technology to strengthen the voice of workers. WeClock aims to do just that. It offers a privacy-preserving way to empower workers and unions in their battle for decent work.

... We live in an age of inequality. Many things are needed to correct current power asymmetries. One of them is to ensure that those who generate data have access to what they’ve made. WeClock provides that access. Another reason is to provide the user (worker) a way to use data in a way that provides them the opportunity to advocate for change in the workplace. A way for solutions to be data-driven, insightful, and owned by those who are the most affected by the shifting landscape of work.

David Roberts in Vox:

I'm looking forward to chatting with the local branch of the Long Now Foundation next week.

For as long as I’ve followed global warming, advocates and activists have shared a certain faith: When the impacts get really bad, people will act.Somehow all this reminded me of a post by an old colleague this week, which in essence said 2020 is bad and getting worse, but at least it's not the jackpot. Luckily he also shared a link, because he meant Heinlein's Jackpot, which I'd not heard of before, not Gibson's.

Maybe it will be an especially destructive hurricane, heat wave, or flood. Maybe it will be multiple disasters at once. But at some point, the severity of the problem will become self-evident, sweeping away any remaining doubt or hesitation and prompting a wave of action.

From this perspective, the scary possibility is that the moment of reckoning will come too late. There’s a time lag in climate change — the effects being felt now trace back to gases emitted decades ago. By the time things get bad enough, many further devastating and irreversible changes will already be “baked in” by past emissions. We might not wake up in time.

That is indeed a scary possibility. But there is a scarier possibility, in many ways more plausible: We never really wake up at all.

No moment of reckoning arrives. The atmosphere becomes progressively more unstable, but it never does so fast enough, dramatically enough, to command the sustained attention of any particular generation of human beings. Instead, it is treated as rising background noise.

... So what are shifting baselines? Consider a species of fish that is fished to extinction in a region over, say, 100 years. A given generation of fishers becomes conscious of the fish at a particular level of abundance. When those fishers retire, the level is lower. To the generation that enters after them, that diminished level is the new normal, the new baseline. They rarely know the baseline used by the previous generation; it holds little emotional salience relative to their personal experience.

And so it goes, each new generation shifting the baseline downward. By the end, the fishers are operating in a radically degraded ecosystem, but it does not seem that way to them, because their baselines were set at an already low level.

... It turns out that, over the course of their lives, individuals do just what generations do — periodically reset and readjust to new baselines.

“There is a tremendous amount of research showing that we tend to adapt to circumstances if they are constant over time, even if they are gradually worsening,” says George Loewenstein, a professor of economics and psychology at Carnegie Mellon. He cites the London Blitz (during World War II, when bombs were falling on London for months on end) and the intifada (the Palestinian terror campaign in Israel), during which people slowly adjusted to unthinkable circumstances.

... Negative changes “are normalized more quickly if you feel like there’s nothing you can do about it,” says Moore. “That might be what’s going on with the coronavirus — people don’t feel like they have agency on a collective level, because the government is not doing anything, so their response is to say, ‘well, I gotta live my life’.”

I'm looking forward to chatting with the local branch of the Long Now Foundation next week.

|

| https://xkcd.com/1321/ |

Spencer Wright in The Prepared writes about Elon Musk:

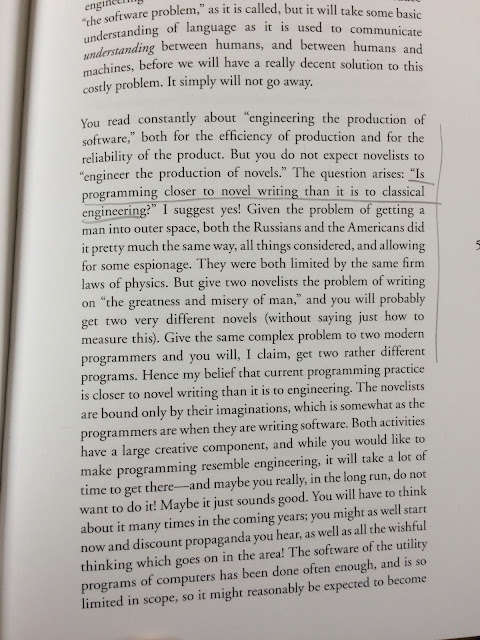

The question to me is: In times when the world feels like it’s existential crises all the way down, is it morally justified for any individual to choose a single existential crisis to devote their lives to? And as a conscious consumer, how should we address companies that (for the sake of argument; the reality is of course *much* more complicated) rate 100% on the environment but significantly lower on labor relations, and social justice, and our collective responsibility to treat COVID shutdowns seriously?Is software engineering more like traditional engineering, or writing a novel? Thanks Martin Kleppmann for highlighting this bit of Richard Hamming's book.

|

| https://twitter.com/martinkl/status/1280137264643944448 |

New research on data challenges in social care (HT Lydia Nicholas)

The Open Repair Alliance continues to collect information about people repairing things.

|

| https://twitter.com/peterkwells/status/1281507661721341952 |

Mmhmm - intro video via Justin Pickard who says 'Pitching itself as the go-to for “people who want to stream PowerPoint instead of Fortnite.”' Looks like it might be a useful tool. My other exciting online chat tool learning this week was from Roland Harwood, who uses a video of a countdown clock as his Zoom backdrop, so everyone can see how long the current speaker has to go.

A long article from Cat Drew at the Design Council about how they see design evolving - including better business, sustainability,

systems, etc. Maybe this might address some of the concerns noted in previous weeks.

Cambridge Global Food Security hosted a webinar about food resilience and the pandemic. It was interesting to hear some debate about the origins of the idea of resilience - from engineering, ecology or elsewhere? Shortages of flour were a challenge in Italy as well as the UK, as catering and industrial suppliers needed to be able to repackage their goods and adapt their distribution chains to serve consumers instead. In France and Italy, people's relationship with food has changed, notably with a growing awareness of overseas farm labour as a key component for local food production. In meat, there's a challenge where complex parts of carcases which would normally be used in restaurants and catering are now available, but home cooks don't have the skills or confidence to attempt cooking them.

Talking Politics with James Meek looked at healthcare, the WHO and the NHS. Another good episode. Notably the point that the NHS has been 'managing' for quite some time by moving the elderly and those needing nursing care into the community, where they are less visible, less counted. It is not a new thing for the pandemic, moving people to care homes from hospitals.

Talking Politics with James Meek looked at healthcare, the WHO and the NHS. Another good episode. Notably the point that the NHS has been 'managing' for quite some time by moving the elderly and those needing nursing care into the community, where they are less visible, less counted. It is not a new thing for the pandemic, moving people to care homes from hospitals.

Tom Steinberg observes that traditional democracies can't talk about COVID-19:

From this incredibly minimal signal – ‘I vote for this person’ – flow a million decisions about taxing and spending, prohibiting and permitting, peace and war, all of which acquire an aura of democratic legitimacy from that one trip to the booth.

... Elected politicians work very, very hard to get elected, and once in position are not enormously keen to give away their hard-won power to other people. Pretty much every single meaningful democratic innovation would mean elected politicians or their unelected executives giving up some of their power: it is a zero sum game.

... COVID-19, and the huge number of fatalities it is causing, changes the basic incentive structure for politicians. To be a key decision-maker now is to be given the unpleasant task of very visibly making hugely unpopular trade-offs between things like the number of dead people on one hand, and the number of children missing crucial schooling on the other.

... Traditionally, decisions on trade-offs like this are kept as quiet as possible to stop them from dragging down political careers. Politicians and their advisors use private models and calculations in which lives, injuries, loss-of-limbs and years-of-education are given financial values. These are valuations which many voters would consider appalling, a denial of the widely held idea that ‘life is priceless’. But politicians can’t avoid these trade-offs – even if they never write their calculations or decisions down, or if they attempt to dodge the issue by making no choice, the trade-off still exists. Even a politician who entirely buries their head in the sand simply ends up de facto endorsing the previous administration’s choices.

... Unfortunately for political leaders everywhere, COVID-19 threatens to break this tried and tested model of burying value-of-life trade off within faceless agencies and committees. Now the question of what sending kids back to school is worth it in terms of the number of lives of older people lost is a dinnertime debate in households across the world.

... For elected politicians this is a nightmare. They simply cannot make clear statements about how many COVID-19 deaths are worth trading for other goods: it is simply outside the territory of things that elected politicians are permitted to say.

... New democratic techniques like citizen’s assemblies offer the possibility of having really tough, specific debates about where to compromise on impossible trade-offs, without politicians being showered in reputational mud that they can never wash off.

Put simply, our governments should experiment with taking some of the toughest, least popular decisions they face in relation to COVID-19, and they should give them to groups of citizens to decide in a transparent, deliberative way. In short, they should do what judges do in jury trials – hand over the really ugly, critical decisions to groups of people who are not worrying about being re-elected, and who have been given the time and resources to really consider the issues in the round.

Cambridge colleagues produced an informative talk about the medical aspects of testing, tracing and isolating - and how the virus spreads. A tad optimistic about where apps might fit in, but that's not what you'd watch this for.

Tess Wilkinson-Ryan writes about the psychology of individual choices around reopening, in the Atlantic.

For social-distancing shaming to be a valuable public-health tool, average citizens should reserve it for overt defiance of clear official directives—failure to wear a mask when one is required—rather than mere cases of flawed judgment. In the meantime, money and power are located in public and private institutions that have access to public-health experts and the ability to propose specific behavioral norms.

|

| https://twitter.com/edent/status/1281109695940395008/photo/1 |

Not only is this an amusing vintage line, it's also authentically vintage. You can't rely on that with viral internet stuff, but Terence Eden checked it out so we don't have to.

A well argued case that we need to build a better social contract from Martin Wolf in the FT [no paywall].

About ten to fifteen years ago, I noticed that American life was getting harder in a bunch of subtle ways. More and more, dealing with problems, like hidden fees on hotel reservations, medical billing issues with my doctor, or problems with gift cards, meant working through increasingly annoying bureaucracies and automated phone trees. Same with filling out human resources forms at work. Many of my interactions with businesses as either a worker or consumer seemed to be coming straight out of the movie Office Space.

I didn’t really understand why until my physical therapist, a wonderful and smart businesswoman, told me about how her industry of independently owned practices was being bought out by a private equity firm. The service her small practice offered was great, with her therapists focused on dealing with the patient’s pain. But the private equity firm, she told me, was gradually buying out competitors in and around Maryland and DC, and corporatizing them. Health insurers made it tough to get reimbursements, so this private equity firm had better bargaining leverage. Corporatized therapy meant checklists and mistreating patients, ignoring their pain and getting them out the door (which would likely drive some of them to take opioids). These twin pressures, of rising market power and concentrated finance, seemed a good explanation for degraded service in a small but important industry.

... Two days ago, FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra issued a comment suggesting the FTC pay more attention to small mergers across the economy, with a specific focus on private equity firms who engage in this kind of practice, which is known as a ‘roll-up.’ In a roll-up, usually in markets with lots of competitors and somewhat low barriers to entry, a private equity firm will buy small privately held companies and combine them into one conglomerate, continuing to buy “add-ons” in the same line of business to acquire market power.... Buying a small family owned business for three to four times revenue, putting it into a conglomerate that financiers then call a ‘platform’ or ‘market leader’, means you can often sell the much bigger company for eight to ten times revenue later on. Is the new bigger corporation more or less profitable? It depends on the industry. But multiple expansion is largely a result of storytelling by financiers to a small club of investors and the ten year period where corporate asset values keep increasing.

There is an entire roll-up expert field, with thousands of private equity firms that are looking for industries to roll-up, some of which are successful and some of which are not.

Matt goes on to describe some unusual industries where this has happened - portable toilets, dentists, mixed martial arts. He also has an interesting anecdote about how franchising agreement structures can affect what relief local franchisees can get.

A few days ago, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) fined Amazon $134k for violating sanctions with Iran, Syria, and Crimea from 2011-2018. Weirdly, OFAC noted that “the statutory maximum civil monetary penalty amount for the apparent violations was $1,038,206,212.” That is a HUGE difference.Thanks to CSaP's newsletter, an article describing the ways Universal Credit works, which might come as a surprise to many.

OFAC is one of the more powerful parts of government, and it doesn’t mess around, because sanctions are one of the few levers that still work and work quite well. Sanctions compliance penalties reached a decade-high level last year. As an example, a cosmetics company did an internal audit last year, realized inputs for one of its products were coming from North Korea, and told OFAC; it was still fined $1 million. Yet, because Amazon would have litigated and lobbied aggressively, it looks like OFAC went easy on the online giant. It is remarkable how even the most aggressive parts of the U.S. government are afraid of Amazon.

Under the Universal Credit rules couples who live together have no right to individual treatment but are obliged to claim jointly, and are treated as a ‘benefit unit’, in which their needs, income and earnings are aggregated. This applies regardless of how long they have been living together, the nature of the relationship, or how they organise their finances.

With the temporary weekly uprating of £20 , the standard Universal Credit allowance for couples aged 25 and over is £594.04 per month, while for two single claimants it would be £819.78 (£409.89 per single claimant or lone parent) – a difference of around £225 each month. That joint claimants are entitled to a lower rate of benefit than double the amount two single claimants get is a feature of the wider means-tested benefit system and is intended to reflect the economies of scale that are assumed to occur when couples share the same household. But this only applies to couples, not housemates or other adult family members. They might also be expected to benefit from economies of scale, so the policy rationale is not consistent....Many couples in our study also reported that there was a large gap between their Universal Credit entitlement and the amount they were actually paid. Deductions were a key reason why. These automated repayments for loans and benefit and tax credit overpayments and council tax arrears, for example, sometimes reduced the payment by 30 or 40 per cent. Seen as particularly frustrating and iniquitous were deductions from the couple’s joint claim for ’inherited’ debts relating to a period from before the couple had even met, when one or both partners had been in a previous relationship. ....

As warned by women’s groups during the early period of Universal Credit’s design, the single payment could also allow one partner to take control of the household’s entire monthly income.

Amazing clouds in Belfast:

|

| https://twitter.com/jennifercobbe/status/1280650450681892865 |