Weeknotes: universal basic infrastructure, feminist perspectives on electricity management, etc

We have for the last 4 years been working on how we can design the means to grow a new system, within a single geography, in Barking and Dagenham. A platform of support has been created across the borough to begin the process of building this new system with the people who live there. This support platform includes a team of people, coupled with processes and infrastructures working together cohesively and strategically to build ecosystems of activity with people’s ideas, energies, skills and dreams are at the epicentre.The way the project handles ideas makes a lot of sense, even if it might be new or surprising to some local businesses and others:

Chris Naylor, Chief Executive of London Borough of Barking and Dagenham (currently on secondment to Birmingham City Council), describes this as the “core architecture for a functioning place”.

The platform (human, physical, digital) is the central architecture and design capacity for co-creating new systems with citizens, alongside existing systems. Everyone, (not selected or segmented groups of people), is invited, welcomed and supported to be part of the co-creation process.

Increasingly we are also identifying that the model development is leading to sets of neighbourhood projects which we can label as ‘universal basic infrastructure’ — different at street, neighbourhood and borough scale.

Much of our economies in the west have been built on the idea of unique ideas, or inventions, which are then protected and monetised. It’s a centuries old way of looking at ideas, but today we also recognise that this method of creating and growing markets around IP protected products has created an unsustainable use of the world’s natural resources and generated too much carbon emission and waste.

Open source and creative commons moves us significantly in the right direction. From open sharing of ideas we can start to think of ideas, services, systems, products and activities which might be essential or basic for sustaining life within the ecological ceiling, whilst also re-inforcing social foundations.

Many agree that it is impossible to move towards a circular economy without incorporating open source products that can be made locally — and it's a massive shift from the dominant mindset right now....We work on the principle that ideas for neighbourhood projects or for collaborative business can come from anywhere. They can come from people living in the borough, or from across the world. The idea itself will always look and feel different depending who is doing it. Additionally all ideas that get developed through the Every One Every Day initiative are automatically open source, meaning that they can be replicated and adapted by anyone in the borough or anyone across the world. This is very different to what we are used to seeing even at neighbourhood project level, where funders and local governments are frequently still looking for ‘social innovations’ or original ideas.

Sharing ideas for neighbourhood projects, inviting more people to contribute means that the ideas often get better, personal risk goes down, the responsibility is shared and is not dependant on one person who might get tired, sick, distracted by life’s other responsibilities like work or family. It means also that people aren’t tied to one idea or project and work across several ideas at the same time, often in different roles or with different frequency or intensity.There's an exciting idea here, which I look forward to seeing develop: We are currently working on building a platform co-operative for making simple circular products. Over the last 18 months we have worked with local residents to develop a set of ‘collaborative brands’.

As households set about the task of adjusting their electricity use in response to shifting prompts, they revealed the importance of managing domestic labour to generate value from DSR products and the role of women in carrying this out. The experience is at odds with the smart future more typically imagined in which chore-doing is handed over to feminized AI assistants who orchestrate IoT appliances to create comfort and capture value. ... The paper argues that chore-doing needs to become a narrative in the smart future to understand the burdens and opportunities for `Flexibility Woman' to create value from her labour. It suggests that women unable to afford a surrogate AI wife may find themselves becoming `Flexibility Woman' or else excluded from accessing the cheaper, greener electricity of the future.

The absence of chore-doing in the design and delivery of smart electricity systems has been identified and comprehensively critiqued by Strengers [27]. Chore-doing should be handed over to feminized AI assistants such as Cortana, Siri, or Alexa who will orchestrate IoT appliances on consumers’ behalf to create comfort and capture value. Such imaginaries have been critiqued by Strengers [27] and Strengers and Nicholls [28] who argue that they stem from a future being built to serve `Resource Man', a consumer archetype drawn by the male-oriented industries of engineering, economics and computer science which are building smart systems. `Resource Man' micro-manages energy through smart home technologies, but is created with in a `smart ontology' that ignores the realities of domestic labour.This all leads to a new possibility - Flexibility Woman:

...It is worth using other frameworks to understand people's participation in the energy system, because as other trials have shown, response to DSR prompts are incorporated into household routines and rationales [26] which can produce confounding results as people act when market logic suggests they would not [33].

....In some respects, the non-punitive offer was able to validate and value the skill of typically unvalued domestic labour, beyond the financial value it gave.

In contrast to `Resource Man' who emerges from future-oriented work as the ideal consumer soon to be realised, Flexibility Woman was visible empirically in the DSR trial. She had knowledge about her family's consumption habits, the loads in home and the schedules of life that shaped her household's electricity demand profile. She may not have talked in these terms or made such connections explicitly, but she had this knowledge because she knew when the laundry had to be done and when it could wait, she knew when meals were to be eaten and therefore when food needed to be cooked. When asked to shift electricity consumption in order to contribute to system level benefits and generate individual rewards, she tried. She differentiated between necessary and indulgent consumption, she arbitraged between gas and electricity, and she developed strategies to recruit other household members into her response, delegating the responsibility to act in her absence, or putting in place simple technical fixes like using a thermos flask to store energy and shift its consumption. She managed her household's energy consumption in line with her management of the household's money and its morality using it to reproduce family values of thrift and discipline or demonstrate family care.There's a great example of a thermos flask as a key 'time-shifting' tool, looking at these low tech ways to manage demand in contrast to the high tech, "smart" kettles and fancy AI controllers which are so common in commercial visions of homes of the future, which suggest increased consumption for some and exclusion for other people.

Domestic labour becomes marginalised in the face of new ways of consuming electricity, rather than recognised as a primary concern and a way of facilitating engagement with and understanding of low carbon transition. A smart electricity grid and associated variable pricing may enable some energy consumers to capture value with their female voiced, app-based domestic manager conducting an orchestra of IoT appliances. People on lower incomes who cannot equip themselves with these substitute wives may find they have to shift or are at risk of being too poor to access the cheapest electricity.

'... the realisation that the welfare net in the UK is incredibly thin has come as a shock to the majority of the population who haven’t had to experience it.’

The balance of the state and the private sphere, in other words, is going to change – and that goes to the heart of government, says Edgerton: ‘We have been living with a crisis of legitimacy of British politics and a hollowing-out of the state to act. Both this epidemic and Brexit have been real tests of that. I had been expecting the realities of Brexit to hit that de-legitimised, incapable state machine, but actually it’s Covid-19 that has hit first.’Tina Fordham says:

So our politics will change: ‘We are going to have a much greater emphasis on the notion that you have to look after society as a whole, not just individuals. And that has important consequences about how we think about the NHS, education, the resilience of the economy and globalisation.’ He adds: ‘I don’t necessarily think the left are going to win. Many on the left are projecting on to the war a particular story of victory of the left and seeing Covid-19 as analogous. I think that’s wrong about the present and it’s wrong about the Second World War.’

‘Economic policy is moving to the left, whether it’s industry bailouts or direct financial support, and that’s regardless of the political orientation of the government,’ she says, speculating as to whether this will lead to the adoption of universal basic income. By the same token, ‘politics are moving to the right when it comes to the biggest peacetime crack-down on civil liberties and civil rights.’Fifteen charities are proposing a data collective to help build shared knowledge of the effects of the pandemic on the most vulnerable, to support better charitable response:

The COVID-19 pandemic and its resulting effects on the UK economy are already having huge negative impacts on our society. Everything from our financial resilience to physical and mental wellbeing is under threat; and people who are already vulnerable will be most impacted.

In order to respond properly, both now and in the longer term, we need to understand what the changes mean. In particular, we need to better understand:These are fundamental questions that many different organisations are trying to answer. But the information we need to do this is held by different people, in different places and can’t be easily joined up. This makes it hard to act on.

- The current and emerging needs of individuals and communities during the crisis

- What services are being delivered to help meet those needs

- Whether those services are effective

- How the lockdown has financially impacted people and the organisations that serve them

This lack of cohesion is a serious issue. It leads to a lack of knowledge.

... We propose forming a data collective: a conscious, coordinated effort by a group of organisations with expertise in gathering and using data in the charity sector. We want to make sure that people in charities, on the front line and in leadership positions have access to the information they need, in a timely fashion, in the easiest possible format to understand, with the clearest possible analysis of what it means for them.

Tom Forth bashed out a quick outline of the state of data and digital government in the UK, which is one of the clearest descriptions I've seen of how the digitisation of government has played out over recent years, where GDS has succeeded or failed, how data infrastructure has worked (or not).

|

| https://twitter.com/rufflemuffin/status/1268289073086693376 |

Tony Hirst tweeted a reminder of some of his experimentation from the mid-2000s around joining up bits of the internet for learning and research.

|

| https://twitter.com/psychemedia/status/1268811716630118400 |

Mostly this made me slightly nostalgic for the era of blog comments, RSS hacks, and so on.

Reilly Brennan notes:

One of the most significant things to happen in the world of automotive technology is this historic change to the AP style guide (link). 'Avoid the term semi-autonomous because it implies that these systems can drive themselves. At present, human drivers must be ready to intervene at any time.' After years of pleading with journalists, editors and AP leaders about this issue, finally there is a positive resolution: there is no such thing as semi-autonomous (nor will there ever be). Conflating 'autonomy' and 'ADAS' features in automotive marketing and media coverage did more damage than it should have. This is a significant milestone because journalists now have a reliable ground truth to avoid this terminology. Of course, automakers can still use ambiguous terms like Autopilot and ProPilot, which 40% of consumers think 'drives itself' (link). One day our DoT will treat automotive technology as seriously as the FDA treats organic yogurt labeling (link). But this is a first, important step.I've been on about this for a while - what we call things matters. "Smart" is fairly problematic, too, although less safety-critical thus far.

I enjoyed Vaughn Tan's thinking about what amorphous organisations might bring to an uncertain world. Adaptability, different modes for inclusion, for instance, but also risks. The point that such collectives are not currently considered, measured or even noticed by those who engage in organisational research is an interesting one. The specifics of the Yak Collective are less interesting to me than the concept.

Liminal fits, to my mind, in the same space as the Yak Collective, but does actually appear countable - there is an entity. (You can find me there.)

In industries that have to be vigilant for risks of disaster, such as aviation or nuclear energy, “near misses” are treated as flashing red lights. When a plane almost misses its landing or a factory explosion is narrowly averted, investigations are made, processes revised: just because the disaster did not occur it does not mean it won’t next time.

But near misses can also breed complacency. We have a tendency, identified by those who study the psychology of risk, to treat near misses as grounds for optimism. Since the worst didn’t happen, people become strengthened in their conviction that it won’t ever happen....The organisational theorists Junko Shimazoe and Richard Burton call this the “justification shift”.

... Western governments, including our own, knew about Sars and Mers but were psychologically distant from problems that afflicted countries far away. That represented a failure of imagination....Awful as this virus is, I wonder what we would be going through now if it was even more transmissible, or if it was killing children in their thousands. We should confront the possibility that what we are experiencing now is itself a near miss.

This quote from Sentiers, which is quoting a Wired piece with Matt Simon interviewing Matthew Flinders:

|

| https://www.wired.com/story/covid-crisis-modern-paradox/ |

And actually, we've got more material goods and material safety than we've ever had, and yet we feel more trapped. That's the paradox of modern life.I also liked:

We live in a media-saturated context, where catastrophizing is the common denominator. If there's a molehill, it will become a mountain. And this degree of social amplification, driven by 24/7 social media, driven by the fact that now everybody can be an expert, the low cost of access to mass global platforms—it means that the noise level is constantly at a very high volume. So I think there is a big issue out there around almost the layering, or sedimentation, of crises upon crises upon crises, that risks eroding our sense of social achievement, actually, and resilience.Some useful tips from Changeist on how to handle all the information there is these days, on social media and elsewhere - useful whether you are trying to do horizon scanning or 'futures' work, or help your organisation respond to current and future events, or just trying to keep up with the world yourself.

Via Francis Irving, a thought-provoking (and entertaining) film about how the classic Hero's Journey narrative might be distorting our ideas of ourselves and what to expect from life.

|

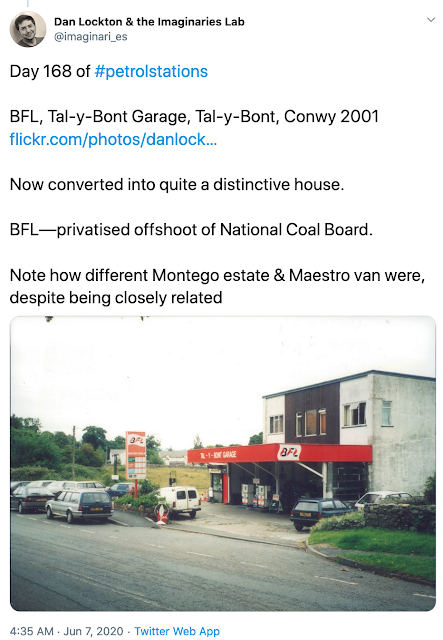

| https://twitter.com/imaginari_es/status/1269473041714606080 |