Monthnotes: premodern internet, technical debt, ageing/longevity

Maybe we've had the wrong visions of the future, argues Max Read. What if we aren’t being accelerated into a cyberpunk

future so much as thrown into some fantastical premodern past? This

article covers bewitched 'smart' objects and the feudalism of big tech

platforms:

Just enough might mean saying no to systems which it is easy to feel are inevitable, given the coverage of them, like machine learning systems which make decisions about people. Julia Powles argues that bias and fairness are distractions from the real issues.

The latest newsletter from Stacey Higginbotham on IOT seems like a reminder of a past internet few of us got to experience - one where ambient devices were joyful, simple, useful.

The Prepared creates the supply chain transparency system Apple should have made:

Continuing my thread around technical debt, I was intrigued to read this paper - "Machine Learning: The High Interest Credit Card of Technical Debt":

Julia Unwin suggests we need to adjust how civil society leadership roles are designed, and how recruitment for them happens.

This piece from Paul Jun reviews Ian Leslie's book Curious which details three different kinds of curiousity: diversive curiousity is about new things, epistemic curiousity, when we are driven to dig deeper, and empathetic curiousity, when we wonder about the feelings of others. (via Sentiers)

A long article by Indy Johar focusses on new governance systems suggested by the challenges facing Asia, but whilst Asia might be "at the forefront of the Great Transition, where the externalities of our old world threaten to make us extinct and new technologies could either emancipate us — or make us redundant" the approaches suggested seem relevant elsewhere. Engaging with 'risk holders' not just risk-taking innovators, focussing on whole teams not 'heroes,' and so on.

Carbon accountability will require basic accountability, first. Gavin Chait describes the need for better corporate transparency and governance in a Twitter thread; he argues that there's widespread awareness of climate issues, and the problem is actually enforcement mechanisms, so campaigns to engage the public might not be the most effective activism.

It was great to see Maintenance as the theme of Sentiers Dispatch 03 (subscribers only), featuring many familiar articles and events, including of course the Festival of Maintenance. The 2019 edition is now available in its entireity on YouTube, so if you didn't make it up to Liverpool you can catch up.

GitHub is setting out to archive open source software for the long term - properly long, in a partnership with the Long Now Foundation and more.

Blockchain hype seems a long time ago now, but of course it's still going on in places. How can these ideas be built upon to create something more collaborative?

On to miscellany.

Utopian and dystopian theories of change from former colleagues.

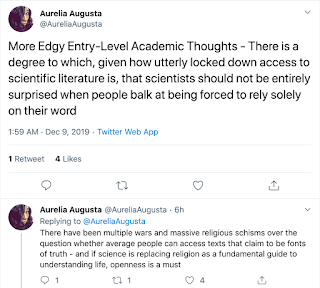

Via Martin Keegan, a mini Twitter thread about how we should perhaps not be surprised at lack of trust in science, given how many publications are stilll locked away, inaccessible to the common person.

Via Diane Coyle, an article on menstruation and work [FT paywall]. There's an exploration of the importance of HRT and why perhaps hundreds of thousands of women in the UK haven't been able to get hold of this critical medication in the last year.

The pros and cons of compostable wraps for post. As ever with these things, it's complicated and the easy answers might not always be right. Since realising that my local authority, despite taking away a wide variety of 'compostable' green and food waste, doesn't take these magazine wrappers, I've been surprised to see how many publications are using them, and I wonder how many recipients know what to do with them (or even if they realise they are different from traditional junk mail plastic wraps).

Heat pumps are a fascinating technology - both slightly magical in how they work, and a great way to move from gas to electric for domestic heating, which we'll need to do to decarbonise the UK. This report discusses how heat pumps could be installed in parks and green spaces.

Learn all about the origins of potatoes in a beautiful essay supported by lots of photography and video.

Long-lived projects are so rare. Here's a 125 year old Latin dictionary endeavour - still going! HT Duncan Reynolds.

Looking around lately, I am reminded less often of Gibson’s cyberpunk future than of J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantastical past, less of technology and cybernetics than of magic and apocalypse. The internet doesn’t seem to be turning us into sophisticated cyborgs so much as crude medieval peasants entranced by an ever-present realm of spirits and captive to distant autocratic landlords. What if we aren’t being accelerated into a cyberpunk future so much as thrown into some fantastical premodern past?The article gives many examples, such as:

And as the internet bewitches more everyday objects — smart TVs, smart ovens, smart speakers, smart vibrators — its feudal logic will seize the material world as well. You don’t “own” the software on your phone any more than a peasant owned his allotment, and when your car and your front-door lock are similarly enchanted, you can imagine a distant lord easily and arbitrarily evicting you — with the faceless customer-service bots to whom you’d plead your case being as pitiless and unforgiving as a medieval sheriff.and

Paradoxically, the ephemerality — and sheer volume — of text on social media is re-creating the circumstances of a preliterate society: a world in which information is quickly forgotten and nothing can be easily looked up. (Like Irish monks copying out Aristotle, Google and Facebook will collect and sort the world’s knowledge; like the medieval Catholic church, they’ll rigorously control its presentation and accessibility.) Under these conditions, memorability and concision — you know, the same qualities you might say make someone good at Twitter — will be more highly prized than strength of argument, and effective political leaders, for whom the factual truth is less important than the perpetual reinscription of a durable myth, will focus on repetitive self-aggrandizement.I'm now the proud owner/wearer of a "Just enough internet" hoodie, thanks to Rachel setting up a charity-supporting store after her valedictory post for Doteveryone.

Just enough might mean saying no to systems which it is easy to feel are inevitable, given the coverage of them, like machine learning systems which make decisions about people. Julia Powles argues that bias and fairness are distractions from the real issues.

The latest newsletter from Stacey Higginbotham on IOT seems like a reminder of a past internet few of us got to experience - one where ambient devices were joyful, simple, useful.

All hail the future of tech-enabled dumb devices

As technology pervades more devices, the assumption is that these gadgets should have some form of internet connection. But some of my favorite gadgets this year have been devices or services that don't require a connection back to the web to work. Instead, they apply sensors and other technology in novel ways to deliver a tech-enabled product that I view as smart, but not connected.Now some of these ideas are getting mainstream - or at least, produced in some volume. Examples include recently released Illumiknobi doorknob.

Rob Martens, futurist at Allegion and the person responsible for the Illumiknobi, calls this style of design "techno-functional," meaning design that pulls technology into things in ways that are scalable, secure, and simple. "Connectivity is a hammer and everything else is now a nail," he says of the current obsession with "smart" products. "Things can be functional without connectivity."

Given the price, security woes, and complexity associated with setting up connected devices, as well as how ambivalent the response to many of those products has been, perhaps 2020 will be the year of techno-functional products. For example, Illumiknobi is an indoor doorknob that has a motion sensor and lights. When you approach the door, the knob senses it and turns on the lights, throwing a pretty pattern onto the door. It's battery-powered, so you don't need to have a smart phone app to appreciate the mix of function, art, and high tech.

...

Another of my favorite products to launch this year was the Casper Glow. The $129 light is designed to sit on a bedside table and follow the ideal lighting for humans' circadian rhythms. It can fade up in the morning to help wake you and gradually dim at night so you can go to sleep. It also has an accelerometer inside so you can turn it over to turn it off, or use other gestures to control it intuitively. If you pick it up at night, it will glow very dimly to light your way without disturbing others.

When the device launched in February, Casper's Chief Experience Officer Eleanor Morgan told Wired, "We feel like there's this interesting opportunity in 'fuzzy tech,' where tech isn't gadgety but disappears into your environment." I agree. And whether we call it fuzzy tech or techno-functional, I think we're going to see more of these devices as companies stop focusing so much on wireless connections to the internet and start using sensors and local machine learning models to put a new spin on familiar products.

The Prepared creates the supply chain transparency system Apple should have made:

Every year since 2012, Apple has released a PDF with a list of their biggest suppliers - the companies that provide, in the words of their 2019 report, "98 percent of procurement expenditures for materials, manufacturing, and assembly of our products."I'm reading Adam Minter's Secondhand at the moment, which explores what happens to products once people get rid of them - there is less useful data, there, with much happening in developing countries and in grey markets.

Some parts of the internet see this as remarkably transparent.

When I began digging into Apple's data... I assumed that Apple had done the work of disclosing its supply chain, and that our job was to focus on metadata. That was a naive assumption. Apple is, depending on when you're checking, the first or second most valuable company in the world; they have roughly $210B in cash on hand. Their CEO, Tim Cook, is widely regarded as a supply chain visionary - the no-bullshit, workaholic ops guy known for negotiating exclusive supplier deals and buying billions of dollars of components at a time, locking in favorable prices and boxing out competitors. And their design department is - like them or not - assumed to be meticulous, punctilious, persnickety.

I get it, though. Just because they've got a lot of money and know a *lot* about their supply chains and are *really* good at communications doesn't mean that they're *actually* committed to supply chain transparency. But their supplier lists go a step beyond an incomplete commitment; they're just sloppy. What about the Fujikura record that's listed in Vietnam but which is really in Thailand? What about The Chemours, which Apple lists (in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019) as supplying parts from a location in Massachusetts when the real factory in Mississippi? What about the fact that Apple refers to the Shenzhen Yuto Packaging Company by four different names throughout the years?

And why publish the reports in PDF (as opposed to CSV) in the first place? And why delete previous years' lists when a new one goes up?

I trend towards cynicism, and see my naivete as a fleeting gift. Apple's supply chain disclosures are an itch just waiting to be scratched - 5,652 partially obscured snapshots of how the world works. I couldn't help but find a way to glean any kernels of information that Apple may have left in their disclosures.

Dong xi (the name means stuff, as in this is how we get our stuff) is a framework to explore the partial snapshots that the Apples of the world give us; it's The Prepared's supply chain exploration tool. And with many dozens of supplier lists in our queue, there's a lot more exploration to come :)

Continuing my thread around technical debt, I was intrigued to read this paper - "Machine Learning: The High Interest Credit Card of Technical Debt":

Not all debt is necessarily bad, but technical debt does tend to compound. Deferring the work to pay it off results in increasing costs, system brittleness, and reduced rates of innovation. ....There's also a recent article on technical debt in infrastructure from Alexis Madrigal, and this topic also gets a brief mention in Nadia Eghbal's note from the end of October --

Traditional methods of paying off technical debt include refactoring, increasing coverage of unit tests, deleting dead code, reducing dependencies, tightening APIs, and improving documentation. The goal of these activities is not to add new functionality, but to make it easier to add future improvements, be cheaper to maintain, and reduce the likelihood of bugs.

One of the basic arguments in this paper is that machine learning packages have all the basic code complexity issues as normal code, but also have a larger system-level complexity that can create hidden debt. Thus, refactoring these libraries, adding better unit tests, and associated activity is time well spent but does not necessarily address debt at a systems level....

In this paper, we focus on the system-level interaction between machine learning code and larger systems as an area where hidden technical debt may rapidly accumulate. At a system-level, a machine learning model may subtly erode abstraction boundaries. It may be tempting to re-use input sig- nals in ways that create unintended tight coupling of otherwise disjoint systems. Machine learning packages may often be treated as black boxes, resulting in large masses of “glue code” or calibra- tion layers that can lock in assumptions. Changes in the external world may make models or input signals change behavior in unintended ways, ratcheting up maintenance cost and the burden of any debt. Even monitoring that the system as a whole is operating as intended may be difficult without careful design.

Is infrastructure getting more expensive bc of the equivalent of technical debt? (Infrastructure in e.g. 19th and 20th century was “greenfield”, now anything new has to build upon existing systems, and maintenance is expensive)

Julia Unwin suggests we need to adjust how civil society leadership roles are designed, and how recruitment for them happens.

There have been programmes to support women, and people from black and ethnic minority communities in their quest to develop as leaders. (As if there weren’t thousands of already brilliant and experienced black and female leaders). And we’ve had decades of fretting about the demand side – do our boards really have the intent and the courage to appoint people who break the mould?A quarter of charity CEOs went to Oxbridge.

And yet, too often senior roles are described exactly as they might have been thirty years ago. The same sets of words – about gravitas (a quality that I’ve never understood, and have always associated with a certain sort of rather pompous entitlement), about administrative and financial acumen, (even though these skills need to be throughout the organisation) about deep and wide networks, (meaning particular and recognised ones) about inspirational leadership, about intellectual prowess – appear with monotonous regularity to describe exactly the sort of person who might have been ideal for the organisation of the past.

This piece from Paul Jun reviews Ian Leslie's book Curious which details three different kinds of curiousity: diversive curiousity is about new things, epistemic curiousity, when we are driven to dig deeper, and empathetic curiousity, when we wonder about the feelings of others. (via Sentiers)

A long article by Indy Johar focusses on new governance systems suggested by the challenges facing Asia, but whilst Asia might be "at the forefront of the Great Transition, where the externalities of our old world threaten to make us extinct and new technologies could either emancipate us — or make us redundant" the approaches suggested seem relevant elsewhere. Engaging with 'risk holders' not just risk-taking innovators, focussing on whole teams not 'heroes,' and so on.

Carbon accountability will require basic accountability, first. Gavin Chait describes the need for better corporate transparency and governance in a Twitter thread; he argues that there's widespread awareness of climate issues, and the problem is actually enforcement mechanisms, so campaigns to engage the public might not be the most effective activism.

It was great to see Maintenance as the theme of Sentiers Dispatch 03 (subscribers only), featuring many familiar articles and events, including of course the Festival of Maintenance. The 2019 edition is now available in its entireity on YouTube, so if you didn't make it up to Liverpool you can catch up.

GitHub is setting out to archive open source software for the long term - properly long, in a partnership with the Long Now Foundation and more.

The world is powered by open source software.Cassie Robinson looks back at previous ideas for ageing well, and what has happened to them.

It is a hidden cornerstone of modern civilization, and the shared heritage of all humanity. The mission of the GitHub Archive Program is to preserve open source software for future generations.

GitHub is partnering with the Long Now Foundation, the Internet Archive, Software Heritage, Arctic World Archive, Microsoft Research, the Bodleian Library, and Stanford Libraries to ensure the long-term preservation of the world's open source software. We will protect this priceless knowledge by storing multiple copies, on an ongoing basis, across various data formats and locations, including a very-long-term archive designed to last at least 1,000 years.

I list all these, because there was so much ‘innovation’ being designed, tested and funded, all with similar intentions, and it’s interesting to look through those lists of projects and programmes, and reflect. There are some great ideas in there, a lot of them were designed and led by ‘older’ people themselves, they made use of design methods, they had lots of support, and yet many of them haven’t survived and I think we are still asking many of the same questions today that each of those initiatives was attempting to respond to.Cassie goes on to say

I wonder why that is? I wonder if one reason is our disrespect and prejudice towards older people, and our denial of ageing. There are projects trying to inspire us towards caring about future generations, and yet we barely care enough for the older generations alive and living in our communities today. Until we shift those cultural narratives and perceptions of the old and the ageing, maybe we’ll never be able to design our way into ‘ageing well.’ There’s also limited space and resource given to better understanding the emotional journey of ageing — how we sustain emotional wellbeing through changing identities and life transitions, and the need for continued intimacy, a topic most people want to avoid recognising.

... it’s really important that we don’t try and design for lives as if they’re individual and separated. As people age, they bring with them trails, tales and tapestries of lived and learned experience, of relationships, and of different places and contexts. There is a bias to design that focusses in on someone’s individual needs but this can lose sense of all of who they are, designing out people’s multitudes, wider contexts and need for belonging, and designing in ways that isolate or disconnect them from their relational identitiesDon't skip the images of extracts from Being Mortal, which describe how we are ageing all the time.

Blockchain hype seems a long time ago now, but of course it's still going on in places. How can these ideas be built upon to create something more collaborative?

In blockchain circles, there is much enthusiasm for DAOs, or decentralized autonomous organizations. These are free-standing, self-organized groups of people who use blockchain tools to structure their members’ interactions and behave as “ownerless” organizations or institutions. The idea behind DAOs is to “allow people to exchange economic value, to pool resources and form joint-ventures, without control from the center, in ways that were impossible before blockchains; and to agree on how risks and rewards should be distributed and to enjoy the benefits (or otherwise) of the shared activity in the future,” as Ruth Catlow of the Furtherfield Collective writes in a crisp foreword.Download the full report.

This is indeed an exciting prospect, but DAOs are generally envisioned as a new breed of “trustless” market organization. They function on the same epistemic plane as capitalism, with everyone treated as isolated individuals looking to maximize their personal (monetary) interests.

DisCOs, by contrast, start from a different set of premises about humanity. They regard we humans as a cooperative species whose members need and want to engage with others, personally. Earned trust among people and open collaboration can then achieve some remarkable things. That’s the essential goal of DisCOs, which consist of a set of organizational tools and practices for people who want to work together in a cooperative, commons-oriented, and feminist economics form.

the report identifies seven principles that characterize distributed cooperatives:

1. Geared toward positive outcomes in key areas (such as social and environmental priorities)

2. Multi-constituent

3. Active creators of commons

4. Transnational

5. Centered on care work

6. Re-imagining the origin and flow of value

7. Primed for federation

On to miscellany.

Utopian and dystopian theories of change from former colleagues.

Via Martin Keegan, a mini Twitter thread about how we should perhaps not be surprised at lack of trust in science, given how many publications are stilll locked away, inaccessible to the common person.

Via Diane Coyle, an article on menstruation and work [FT paywall]. There's an exploration of the importance of HRT and why perhaps hundreds of thousands of women in the UK haven't been able to get hold of this critical medication in the last year.

The pros and cons of compostable wraps for post. As ever with these things, it's complicated and the easy answers might not always be right. Since realising that my local authority, despite taking away a wide variety of 'compostable' green and food waste, doesn't take these magazine wrappers, I've been surprised to see how many publications are using them, and I wonder how many recipients know what to do with them (or even if they realise they are different from traditional junk mail plastic wraps).

Heat pumps are a fascinating technology - both slightly magical in how they work, and a great way to move from gas to electric for domestic heating, which we'll need to do to decarbonise the UK. This report discusses how heat pumps could be installed in parks and green spaces.

Learn all about the origins of potatoes in a beautiful essay supported by lots of photography and video.

Long-lived projects are so rare. Here's a 125 year old Latin dictionary endeavour - still going! HT Duncan Reynolds.