Monthnotes: AI and phones, fragility of tech and climate; a Venn diagram

A lot of notes this week fortnight month, but stick with them. There's a comic at the end.

Tech miscellany to start with.

We need to communicate better about technology. Ronald Dworkin breaks down issues with how we describe AI:

Sadly I couldn't make it to Mozfest this year, and also missed my colleague Rachel Coldicutt's talk at Mozfest House on how the right public service internet might be "just enough internet." It's a good read - some highlights:

History is still something I feel I barely know anything about, so I enjoy the fragments of ideas I can pick up. Via David Edgerton, an interesting article about the dangers of a buccaneering view of British history:

From the Kneeling Bus, a piece about how our social connections now depend on computing and on energy consumption, and how fragile they are (highlights mine):

A few weeks ago, this piece by Quinn Norton on our growing need for resilience to handle infrastructure failures was doing the rounds:

There's more on the code in question on Wired (via Patrick Tanguay). Catalonia protesters (Tsunami Democràtic) are using a mix of twitter, Telegram and their own distributed app to organise - the app is particularly interesting because it doesn't do broadcast, but limits who sees what. It's not distributed through the app store, which would be easily subject to censorship.

What are we supposed to do about consumer technology problems? Vicki Boykis reviews Snowden's memoir on Normcore Tech:

Chris Adams ran OMG Climate in London - an event to help tech folks find things they can do about climate change. The nice thing about this is that there's a kit so you can run your own, where ever you are.

Changing climates and ecosystems changes the patterns of disease, too. Mosquitoes and ticks are bringing diseases to new places - Malaria moves North into Greece, for instance, and here in the UK, tick-borne diseases (often deeply unpleasant and life-changing) are on the up.

Tom Forth has read the report into the Irish Citizens' Assembly on "how the state can make Ireland a leader in tackling climate change" and summarises some thoughts. Citizens' Assemblies seem a good idea - a way forward out of some of today's challenges with representative democracy - but they do take a lot of work to be effective. Tom's points about the recommendations here seem very pertinant.

Michelle Thorne writes about climate and internet, and proposes that we need to refocus from production to understanding:

In the meantime, we can still share things online! My former colleagues at Field Ready and the MakerNet Alliance and friends have published the Open Know-How specification.

A great piece from Adam Minter describing the modern day rag trade. More reuse than recycle.

How do you keep on keeping on?

Deb Chachra is inspiring as ever - capturing exactly my thoughts in a lovely Venn diagram:

And yes, this needs a gloss, and luckily Deb provides one:

“Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation” is Scottish writer Alasdair Gray’s rephrasing of a line from beloved Canadian poet Dennis Lee (the original was "a better world").

“The Jackpot” comes from William Gibson's novel The Peripheral, and is a distributed, slow-motion apocalypse of climate change, crop failures and famine, pandemic, political collapse, etc.

Thanks, Cat and Girl. It's been weeks since I was in these fields.

It's been a big week at work with the lowRISC team in Cambridge, as we announced OpenTitan, an exciting open hardware project using lowRISC's collaborative engineering model to create the first open source silicon root of trust. You can follow our progress on GitHub.

Tech miscellany to start with.

We need to communicate better about technology. Ronald Dworkin breaks down issues with how we describe AI:

To keep people in the small world from behaving more ridiculously, or from experiencing more loneliness than they already do, and to head off a potential conflict of religious proportions, we must tell AI’s inventors to set the right tone. No more confusing the passive with the active. Such careful language was unnecessary in the past. People could get away with being lazy and sloppy, and saying that an ocean wave “causes” events. No longer. With the rise of AI, we must be more precise. We must declare AI a bunch of silicon and metal, with no more power to “cause” than an ocean wave.This piece about AI and radiology, how the technology actually works today and what it needs to be capable of to be useful, is accessible and clear.

Three years ago, artificial intelligence pioneer Geoffrey Hinton said, “We should stop training radiologists now. It’s just completely obvious that within five years, deep learning is going to do better than radiologists.”I use the example of image-processing machine learning coming up with diagnoses based on the 'photo frame' showing the scanner model in use quite a lot in talks about machine learning shortcomings. Different scanners are used in different contexts, so some will be more likely to be scanning patients with worse conditions, which is a nice correlation for a machine learning system to decide to use.

Today, hundreds of startup companies around the world are trying to apply deep learning to radiology. Yet the number of radiologists who have been replaced by AI is approximately zero.

Sadly I couldn't make it to Mozfest this year, and also missed my colleague Rachel Coldicutt's talk at Mozfest House on how the right public service internet might be "just enough internet." It's a good read - some highlights:

..if Netflix and YouTube want to keep us stapled to the sofa, then perhaps the BBC should take us – metaphorically or in reality – into the fresh air.

... It is time to stop following big business, and think back to the social contract. How can digital public services be part of a strong and resilient society?

... If the answer from business is to add data to everything, then perhaps the public sector should be more measured. Perhaps a public service Internet should be a model of restraint; a counterweight to the ballast of peak data, that knows and provides just enough.

... Mary Meeker predicts that by 2020, only 16% of the world’s data will be structured enough to be useful. Or to put it another way, 84% of the data collected about people and things is sitting unused. Using up servers, eating electricity.

... Just enough Internet might be all the planet can afford in the future.I have a new phone. It's a Fairphone 3 and I'm really impressed - long battery life, a couple of features my four year old Fairphone 2 was lacking (NFC, for instance). A reasonable price for a fairly traded, repairable, but otherwise unexceptional phone (TechCrunch has a good review.). If I lived in Africa, maybe I'd get a Mara phone - made in Rwanda! 2019 is a good year for phone innovation in unexpected forms.

History is still something I feel I barely know anything about, so I enjoy the fragments of ideas I can pick up. Via David Edgerton, an interesting article about the dangers of a buccaneering view of British history:

History is politically powerful, because it serves as a proxy for ideology. From Boris Johnson to Jacob Rees-Mogg, and from Dominic Raab to Liam Fox, Leavers use the past to imagine the future. They make historically based claims about Britain’s “natural” allies, markets or place in the world, based on curated memories of war and empire. They invoke the achievements of former generations as a model for the present; and, in so doing, give the false assurance that the path down which we are walking leads to old and familiar places. As so often, history becomes the mask worn by ideology, when it wants to be mistaken for experience.Diane Coyle's latest book review includes a nice term - slicing economy:

These histories owe less to academic writing than to what might be called second-hand dealers in the past: politicians, newspaper columnists and media commentators, who rummage through the scrapyard of history, pulling out the most useful parts and welding them together into a vehicle for their ambitions. The products are then marketed to the public through the most dangerous word in popular history: “we”. “We won the war.” “We survived the Blitz.” “We abolished slavery.” It is a word that allows us to pin other people’s medals to our chests; to demand gratitude for other people’s sacrifices; and to boast of victories bought with other people’s blood. It creates a false equivalence between past and present, in a way that can dull our sensitivity to change.

"Woven through the book, too, are examples of how digital technology is changing the size of lumps or making slicing more feasible – from Airbnb to Crowd Cow, “An intermediary that enables people to buymuch smaller shares of a particular farm’s bovines (and to select desired cuts of meat as well),” whereas few of us can fit a quarter of a cow in the freezer. Fennell suggests renaming the ‘sharing economy’ as the ‘slicing economy’. Technology is enabling both finer physical and time slicing."It would be great to be able to reclaim "sharing economy" one day!

From the Kneeling Bus, a piece about how our social connections now depend on computing and on energy consumption, and how fragile they are (highlights mine):

But what is true about the new social infrastructure that replaced the old is that the new infrastructure is literal infrastructure—electronic devices and fiberoptic cables and data centers and the energy that keeps it all flowing—and now our ability to communicate with even our physical neighbors depends more on that system than on any localized community we can access easily without software's assistance. That generally doesn’t matter, because the technology almost always works, but when your phone dies while you’re out of the house, you realize how little is left of what preceded the digital revolution. When the power goes out, in many cases, you really are isolated (finally).Returning from Maintainers III with all the discussion about climate and economic fragility, this piece struck me as particularly interesting. We forget our dependencies on social connections and communication easily.

One side effect of software eating the world is that many formerly low-energy activities now require a constant supply of fuel to keep happening. Reyner Banham, describing the various technologies that facilitated the settling of the American wilderness, observed that American-made Jeeps became less versatile and rugged as the infrastructure for driving got better and they no longer had to traverse rough terrain. He also noticed that Coca-Cola vending machines were popping up in remote western towns, and wrote that these machines “imported into their surroundings a standard of technical performance that the existing culture of those surroundings could no more support unaided than could the Arkansas territory when it was first purchased." Today, we could say the same about many of the physical environments where we spend our time—most of our buildings, streets, and cities were built long before our iPhones were and are correspondingly “dumb,” optimized for forms of analog collectivity that only still exist symbolically, if they still exist at all. The devices themselves, by contrast, bypass all of that and connect to a global stack for which cities are just clusters of end users and sources of data. If a few of us sit in a room together, we can all turn our phones off and talk, the same way people have for millennia, but to organize anything more complex, now, we need infrastructure.

A few weeks ago, this piece by Quinn Norton on our growing need for resilience to handle infrastructure failures was doing the rounds:

One of our jobs in this century is to accept that we don’t live on the planet we thought we lived on, and our societies aren’t doing what we thought they were. Even if we were able to change our politics overnight, which is probably impossible without some planetary level disaster wake up call, it would still take many decades to dig ourselves out of out technical debt, and in the mean time, we have to stay alive and try to thrive.

Everyone who lives on this stressed-out planet have to have plans, at every level from transnational to individual. We have to build resiliency and capacity to cope with unstable and difficult circumstances, potentially for years, as we learn to pay down the technical debt and build the infrastructure that can work with our planet.

....

Both modernizing existing infrastructure and building new sustainable infrastructure at once is slow and viciously expensive. Doing one after another is slower, a little cheaper, and more dangerous. These are the trade-offs that will characterize life in the 21st century on our lovely little water planet.GitHub was blocked in Spain for a while because it was being used to distribute code used by protesters. GitHub definitely counts as critical digital infrastructure for many projects now, and whilst we may trust Microsoft (who own GitHub now) to continue to run fairly well set up servers and to have engineers working on uptime and so on, that's not the only thing necessary for infrastructure-grade resilience and service.

Our incentives often undermine these goals at every level.

As a simple example, power cuts lead to people buying generators, which are worse for climate change than power generation. This is a pattern we see all over the developing world, like the otherwise modern lifestyle in Beirut, but now showing up in the developed world.

There's more on the code in question on Wired (via Patrick Tanguay). Catalonia protesters (Tsunami Democràtic) are using a mix of twitter, Telegram and their own distributed app to organise - the app is particularly interesting because it doesn't do broadcast, but limits who sees what. It's not distributed through the app store, which would be easily subject to censorship.

To ensure the app remains in the hands of genuine protestors, rather than police or other infiltrators, users can only access it through a QR code from someone who is already a member of the network. Each person who joins receives ten QR codes to invite others.This is interesting. I remember - quite a long time ago now - talking with John Naughton about activist networks, hierarchy and decentralisation, and the social and technical aspects of these. This app is trying to do something quite unusual, and the open source components should enable audit and trustworthiness - although this still takes work:

The app also employs geolocation technology to coordinate activity. When you first download the app, you’re asked for your location (a loose estimation rather than exact coordinates). This means people can be organised in geographical “cells”, and protestors can only see actions taking place within a certain radius – preventing information from sloshing out across the network, and limiting what an infiltrator would be able to find out.

Some of the app’s source code – not all of it – has been released publicly, and technologists have scoured the publicly available parts of the code for indicators about the app’s inner workings.Despite all this, it's still potentially a risk:

The app is built on top of Retroshare – a freely available software used to construct encrypted, friend-to-friend networks (peer-to-peer networks in which users only make contact with people they personally know) to share files or communicate without relying on any central server. “In this mesh, nodes only exchange data with their connected ‘friends’, in order to maintain anonymity between non-friend nodes,” says Cyril Soler, one of Retroshare’s developers. “On top of that, Retroshare implements different techniques to allow data to be passed from node to node beyond your direct friends. That, for instance, allows the software to globally propagate distributed mail or files.”

While the app is decentralised in terms of nodes, experts have speculated that there might be some users who can see an overview of the app – where protestors are active and available across the city. However, whether this is the case is not clear from the publicly available code.

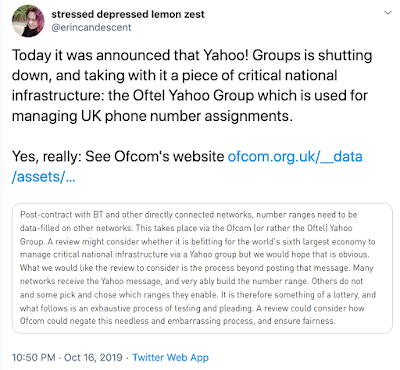

Despite the app’s precautions, some concerns still remain. “Its traffic would be quite unusual, especially coming from mobile devices, which would probably make it easier to analyze and inspect for ISPs [internet service providers] – although I don't know if the authorities can legally request this kind of information from Spanish Internet Service Providers (ISP),” says Sergio Lopez, a software engineer, who has independently analysed Tsunami Democràtic’s publicly available code.Sometimes, technical fragility is more prosaic:

“This means that, even if the contents are encrypted, ISPs could potentially build a relationship map of nodes participating in this kind of [friend-to-friend] network.” It’s for this reason that other protest movements, such as the one in Hong Kong, rely on Bluetooth, thus avoiding and ISP's network.

|

| https://twitter.com/erincandescent/status/1184587323599736837 |

What are we supposed to do about consumer technology problems? Vicki Boykis reviews Snowden's memoir on Normcore Tech:

what were we supposed to do? In 2017, after writing about what Facebook collected in detail, I stopped posting there. I started using Duck Duck Go. I covered my computer camera with a sticker. I started using VPN.This is very relatable.

Was any of this enough? In the book, Snowden makes a nod to GDPR, and talks about the importance of encryption. But, if Apple, Google, and Facebook are hosting NSA servers, can we, as individuals, really do anything about it?

The way I personally have been dealing with all of the things he talks about in the book is through cross-hatching. In “It’s Only a Joke, Comrade”, a book I’ve written about before, the author talks about the idea of cross-hatching: living with two very disparate realities at the same time by keeping them separate in your mind so you don’t get cognitive dissonance. Not unlike doublethink, but not specifically related to politics. In the case of the book, the author was talking about die-hard communists who loved the idea of the Soviet Union, and at the same time had to live through the atrocities of Stalinism and somehow deal with both realities.

In today’s world, it means that I cover my computer camera with a sticker and yet carry with me almost at all times a cell phone that can record my every move.

It means that I have stopped posting pictures of my kids online in public, but they’re still uploaded to Google Photos, which nicely organizes them, and uploads them directly to the cloud, through the NSA.

Chris Adams ran OMG Climate in London - an event to help tech folks find things they can do about climate change. The nice thing about this is that there's a kit so you can run your own, where ever you are.

Changing climates and ecosystems changes the patterns of disease, too. Mosquitoes and ticks are bringing diseases to new places - Malaria moves North into Greece, for instance, and here in the UK, tick-borne diseases (often deeply unpleasant and life-changing) are on the up.

Tom Forth has read the report into the Irish Citizens' Assembly on "how the state can make Ireland a leader in tackling climate change" and summarises some thoughts. Citizens' Assemblies seem a good idea - a way forward out of some of today's challenges with representative democracy - but they do take a lot of work to be effective. Tom's points about the recommendations here seem very pertinant.

Michelle Thorne writes about climate and internet, and proposes that we need to refocus from production to understanding:

I still hold on to the belief that when humans can genuinely connect with one another, we can tap into an empathy and creative potential that transcends language, nationality, ethnicity, class, and whatever other barrier we’ve erected between us. My friend Renata Avila called it digital internationalism. Yochai Benkler described it as commons-based peer production.There's a lot in there. Commons-based peer production seems like a good alternative to other forms of production, but it's still about generating new stuff, and that perhaps isn't the greatest emphasis for a new way of doing things in the coming years. The internet could certainly be used differently than we use it today, with more use in empathy and care. At the same time, human nature is what it is; and I wonder if the growing(?) divide between solidarity and self-interest may mean the 'empathy network' might be a naive utopia?

I’d like to suggest that these days we’d benefit from focusing less on production and usefulness and more on some sort of commons-based peer understanding.

This worldwide empathy network is at the kernel of why I still care about the future of the internet. I think we should be doing more to look inwardly and locally. But this work is situated on a planet with many living beings all intertwined with one another. You won’t fight for what you don’t love. And it’s hard to love someone or something you don’t know or feel alienated from. And in this weird way, and kinda despite what it is right now, I love the internet because it helps us expand our circle of care.

We need some sort of caring mentality for the internet itself, not because of what it is today, but what it could be: a true exchange among people for our own understanding and preservation.

In the meantime, we can still share things online! My former colleagues at Field Ready and the MakerNet Alliance and friends have published the Open Know-How specification.

Open Know-How is all about sharing knowledge on how to make things. With dozens of open hardware organisations and over 80 content-hosting platforms and thousands of designers sharing open hardware designs, there is little consistency as to how know-how is documented or shared. Makers struggle to locate what they need, not knowing which platform to find it, what the intended use is and therefore struggle to adapt designs. Whilst the knowledge is 'open', it is not freely flowing in the spirit that open-ness suggests.Know-how around making is a tricky area to share knowledge about, because you need a mix of qualitative and quantitative information, different objects can need very different instructions, and yet there's value in a structured presentation. How do I know if the object I make will work well? What parts of the design can be changed to match local material or equipment availability? What can be customised? I wrote about some of these issues in a 2017 paper.

The objective of this specification is to improve the open-ness of know-how for making hardware by improving the discoverability, portability and translatability of knowledge.

Knowledge, unlike data or information, is tacit. Documentation and representation of knowledge can take different forms for different types of hardware and audience, and specifying how knowledge is represented can limit innovation and usability in different contexts. Therefore, this specification introduces a maturity model for increasing specifications for knowledge. The intent is that a designer or platform can choose to adopt this specification appropriately, rather than an over-prescriptive approach that deters adoption.

A great piece from Adam Minter describing the modern day rag trade. More reuse than recycle.

It’s a quirk of the global economy that the most direct beneficiaries of the rise of fast fashion might be paper towel manufacturers.The more I learn about waste from Minter's writing the more astonishing it is. He goes on to say:

...

None of the cut-up sweatshirt fragments through which Wilson is rummaging were used in India. Rather, they were likely made in South Asia, exported to the U.S., and worn until they were donated to Goodwill, the Salvation Army, or some other thrift-based exporter. When they didn’t sell there, they were exported again (to India, most likely), cut up, and exported again—this time to Star Wipers in Newark. Each step of that journey makes perfect business sense, even if the totality of it sounds ridiculous.

In fact, it’s the future.

Middle-class consumers in Asia already outnumber those in North America. For now, Wilson says more than 82% of Star Wipers’ rags are sourced in the U.S. But soon, unwanted secondhand stuff from Asia will exceed what’s generated in more affluent countries. If those clothes don’t sell, they can always be cut into wipers, assuming the quality is sufficient. And those rags, sourced from clothes worn and cut in developing countries, will make their way to the U.S. A secondhand trade that once flowed in one direction—from rich to poor—now goes in every direction.

How do you keep on keeping on?

Deb Chachra is inspiring as ever - capturing exactly my thoughts in a lovely Venn diagram:

|

| https://twitter.com/debcha/status/1193143681181736961 |

“Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation” is Scottish writer Alasdair Gray’s rephrasing of a line from beloved Canadian poet Dennis Lee (the original was "a better world").

“The Jackpot” comes from William Gibson's novel The Peripheral, and is a distributed, slow-motion apocalypse of climate change, crop failures and famine, pandemic, political collapse, etc.

|

| http://catandgirl.com/at-work-in-the-fields-of-the-lord |

It's been a big week at work with the lowRISC team in Cambridge, as we announced OpenTitan, an exciting open hardware project using lowRISC's collaborative engineering model to create the first open source silicon root of trust. You can follow our progress on GitHub.