2018 yearnotes

I write weeknotes, so why not yearnotes?

I made a concerted effort in 2018 to work more in the open, blogging events and ideas, and also since September writing weeknotes. The weeknotes are a bit of a grab bag of things I’ve read or seen, conversations I’ve had, fragmentary bits of synthesis where there seems to be any. Publishing rough notes, without any serious thought about a reader (sorry), is a discipline which encourages me to put time into reflecting, which otherwise probably wouldn’t happen. You, dear imaginary reader, are a tool for personal accountability. It is an effort to write weeknotes; they take time. Reflection takes time, and with a set of part time jobs at present, only one of which is paying me to do anything like this (and then only partially), it’s good to have a reason to make myself step back a bit.

With yearnotes I suppose I am stepping back another level; possibly it would be worthwhile doing this more than annually, and perhaps about specific topics. One thing my weeknotes show clearly is that each week there are diverse topics catching my eye, and although I can probably sketch out a few recurring themes, they are all happening in parallel — and most of them are not topics I am actually working on, in a paid sense. There’s not been the clear blocks of time to synthesise any one of these strands, or sufficient bits of time to work through them with others, as I generally think better with others. These yearnotes are undoubtedly biased towards the last months of 2018, and especially to the reflective period of December. So they may not be a particularly good reflection of the year. They are very much like my weeknotes, a random collection of quickly typed notes.

One of the real highlights this year has been rich and fascinating encounters with people from humanities and social science, and their really different perspectives and ways of thinking and working. Just attending a history lecture is eye-opening if you’ve done most of your education in a scientific or technical field. Another good thing in 2018 was making time for random chats with diverse interesting people, even when there wasn’t a specific topic or purpose for the conversation; these have been super, inspiring and educational and useful in all kinds of ways. I’m going to make sure these keep happening in 2019, with contacts new and old, and including the very few people where it sometimes seems hard to get a conversation like this going.

2018 felt like a year of treading water professionally, but I end it highly motivated to change that, which I guess is good. At the start of the year, I wanted to do more work with new technology, but opted instead to focus on capitalising on the pioneering work I’d been doing around responsible and ethical tech at Doteveryone, which was distinctive and ahead of the curve. Establishing the Trust & Technology Initiative at the University of Cambridgewas a great way to do this, and let me shape something focussed on the longer term questions around the internet, society and power which neither Doteveryone, nor the wider emerging “tech ethics” community are looking at. I’m really pleased we’ve created something distinctive and valuable, especially at a time when it would have been easy to follow the hype and the herd to fixate on artificial intelligence and data and very short term concerns. Instead of just critiquing the status quo — very easy this year, and not something we need a lot more of — we are thinking about how we can do better in the future. I’m also proud that we’ve identified how we can be most useful, in starting and supporting conversations that otherwise weren’t happening across disciplines and sectors.

The job title of Entrepreneur in Residence was a nice bonus, although it took many months for me to feel fine about being described as an entrepreneur. (The startup world has a very particular idea of what one is, which isn’t me, and which is especially tainted this year as more people see the damage done by startups lauded in the past. But in other contexts, it’s not so bad.) I scaled back my Doteveryone activities, handing the delivery of the responsible tech programme over to the competent hands of Sam Brown. This let me focus on providing more technology expertise to the team, and to avoid having to commute to London multiple times a week. It’s been good to focus on the more technical communities we work with (such as the Partnership on AI, where I am part of the safety-critical AI working group) too. I’ve not done as much other work around tech ethics though — I should probably have hustled for consultancy more, especially as I know hustling is a weak spot for me. I sit on the ethics committee of the Machine Intelligence Garage (paid work!), and I’ve had a couple of exploratory calls with businesses looking for help around being responsible in their tech development activities, but much less paid consultancy than I would have liked. I’ve had some nice speaking opportunities, but generally of the “worthwhile” rather than “lucrative” type. Incidentally it’s been good to reconnect with the internet of things world a bit, after ten years, and to find it not much changed. (If you need some help exploring the trustworthiness of your technology, in helping your product and tech teams be more responsible and ethical, get in touch!)

I was doubtful whether I ought to be running a festival, but a few of us pulled together the Festival of Maintenance in September, and it was lovely. The coverage on the BBC World Service and in the Economist was an unexpected bonus. Our team is bigger for 2019 (more volunteers still welcome though!) and we’ll be getting out of London (where there are too many events) for a better venue in Liverpool.

I had no idea, a year ago, that I’d be part of a team figuring out how to support change-making ventures in a new way. We launched the Impact Union this autumn, and it will be becoming a reality — a prototype at least — in 2019.

September was busy, with the Festival and the Trust & Technology Initiative launch, but once these were done and I’d divested myself of the time sink that was active involvement in the Digital Life Collective, I resolved to have more conversations about potential future projects, and with interesting people in general. I did pretty well at this and will continue to make time for random chats in 2019. Rather late, I also serendipitously found a way to catch up with the state of cutting edge technology as I’d originally hoped to do at the start of the year. With the departure of the previous research facilitator, who coordinated industry collaboration at the Computer Lab, an interim opportunity opened up to be more involved with the department. (Although the Trust & Technology Initiative is formally based there, most of our work is across the University at large.) It’s been lovely to be embedded in such an amazing computer science department, and, as I’m not in an academic post, to have the chance to catch up with what is going on across all the research groups and projects.

What did I think I was working on in 2018? It was July before I wrote something about this, trying to show how the various strands fitted together. Something about internet technologies, how we resource things (public and collective goods, such as open knowledge, but also the business models that enable services to operate), how they are owned/controlled (and therefore what risk capital is able to support their creation), and how we know what good looks like — what we measure and what it means.

That post mostly still applies, except for the bit about the Digital Life Collective. I should really have stopped putting time into this sooner — nothing much changed in the year up to my departure in September and the problems were clear from very early on. (I have not, as yet, set about creating the thing I hoped the Collective would be.) 2018 certainly saw the issues with the way we’ve been developing and deploying tech for a while reaching mainstream attention; in mid-2017 that seemed like it could still be a long way off. State action to deal with some aspects of surveillance capitalism, the attention economy and the level of irresponsible tech is certainly coming now, and many good people are working to make sure this is the thoughtful and appropriate regulation that’s needed. Doteveryone’s work on digital understanding, especially for leaders and decision-makers, looks very relevant and prescient.

More people have left Facebook. I still feel this is a fine thing to do, if it works for you, but mass departures are not the solution to the problems it has caused, and leaving such a socially useful platform is something not everyone is able to do. Small businesses need Facebook to reach their customers and markets; individuals and community groups rely on it for connection.

There’s still work to do in building viable alternatives, systems which offer useful connectivity and services, which are pragmatically designed, with new business models and ways of thinking about what is important for tech. Several events in 2018 were great for exploring ideas here — I’d particularly call out the Public Stack summit, OPEN 2018, and the BBC/Mozilla Healthy Public Service Internet workshop.

None of these have yet given me the sense of a viable project to work on though. The closest is Oli Sylvester-Bradley’s “planet” concept, or something similar, which I roughed out some ideas for. It still feels too big. I think we need to look smaller, at more local, relevant and appropriate technology. In humanitarian aid or development, no one would dream of proposing a tech solution which would work everywhere or scale to the whole planet, or even a set of countries. Local and appropriate technology is essential. So why do we persist with the Valley-style idea that we need to go big, or go home? More and more it feels like smaller services, doing something useful for a modest number of people and well designed for their needs, with connections to other systems if required, is a better way to go. Such things might be supported through revenue, rather than endless VC rounds, and be better matched to the investment markets in Europe, or in the UK in a presumably post-Brexit situation.

You need risk capital to do risky things, that might not work. Today’s “tech VC” which is so often about funding marketing, a rather different risk (and learning) than technical risk and the learning from trying to solve engineering problems. I still have to remind myself that what I think of as tech, and what I find interesting, is now called “deep tech” in the startup scene.

The discussions at our CRASSH research network, ostensibly about open intellectual property and emerging technologies (mostly ‘deep’ too!), have been excellent this year. I’m very aware that the topics we are picking at aren’t really about IP as much as the general question of how new technologies can be developed and can help tackle problems (especially in poorer countries), and specifically where money comes from to do this, and once developed, how such tools/products/systems can be sustained. We’re trying to double down on economics this year, but we aren’t yet sure if economics (in the scholarly sense) has the answers, so perhaps we’ll also try business studies. It feels like our question has shifted from the original: the guiding question of our research group will be the extent to which open technologies result in equitable sharing of knowledge and cognitive or technology justice. I would say we have a broader question, of the extent to which different methods of resourcing technology development and operation result in equitable sharing of knowledge and cognitive or technology justice. Open IP might be part of this, but it’s more than that.

It was also good at the end of the year to go back to Cameron Neylon’s 2017 paper on collective action and infrastructure. This also points to smaller groups or communities as being easier to create shared goods for. There’s also something which echoes the ‘next generation internet’ conversations, as well as questions of equity — the idea of designing for worst-case scenarios, not just following best-practice models. There will be threats and bad actors, and we should design with those in mind (those we can anticipate, at least).

The Festival of Maintenance has introduced me to people like David Edgerton, Lee Vinsel and Andy Russell, who have really challenged the way I’ve thought about technology. It’s not just the question about how much we, in rich countries, focus on innovation rather than operation and maintenance, and get (excessively?) excited about new things whilst forgetting about looking after stuff. It’s also about the way we think about how new technologies arise in the world, which ones get developed, and how, where and why they get applied to which problems. Being back in a University context (probably temporarily, again) reminds me of the dominant “tech transfer” narrative, of ideas incubated in academic departments, then transferred out (with IP, or people, or whatever) into the world of business (or perhaps into the poor world, now we have the Global Challenges Fund to support research which acts as overseas aid), where they are “scaled up” or “diffused.” I’m less convinced of this, now.

So, 2019. I’d like to be building something, working on a venture or challenging big project, using my problem-solving skills and working in a team, but what? There is a lot to do in internet technologies that people use every day, but despite encountering many projects over the last couple of years, nothing has stood out as the right place to put my energy. There are blockchain-ish projects, distributed/decentralised projects and so on, generally seeming notably flawed or impossible to understand in enough depth, sometimes due to proximity to the messy cryptocurrency hype or cults of personality. There will be new endeavours especially around distributed machine learning; hopefully some will actually deliver useful services, but I struggle to see meaningful value in most of these where people are concerned, simply because I am not sure we are measuring or optimising the right things. (Machine learning for technical systems, monitoring power infrastructure, say, or building structures, or network security — systems where there are sources of relevant and useful data and where it is clear what ‘good’ looks like — increasingly seem more viable to me.)

Maybe the ideas generation stuff needs more work. The exploratory events I mention above were great, but it felt like they needed just a little longer, more time to dive deeper, to enable more concrete ideas to emerge that there would be momentum to take forward. There’s still convening to be done, bringing together people from these slightly different worlds (open source, distributed systems, co-ops, design, etc), creating space and time for deeper constructive discussions. There needs to be some sort of framework, a guiding direction, some constraints; just waiting for “emergence” won’t help. (There’s been a great thread on nettime this week which critiques this, as well as some other ideas for an “Anthropocene Socialist” movement… and the Digital Life Collective experience also brought this home to me. Great intentions, but not enough structure or direction for any new growth to take hold. Ultimately, it comes down to a set of social issues — how do we collectively do things, whilst respecting different mindsets (such as introversion), emotional labour, and giving everyone a balance of challenging labour and rest?)

Pending a suitably connected and positioned organisation doing this convening, and in the absence of an idea and a team to work on a human-facing internet problem, tackling problems elsewhere seems more appealing. Increasingly I think that means looking at climate and sustainability stuff, and I have a sense that there’s more I could do to build on my previous experience around manufacturing and materials, and energy. These seem like they might be more fruitful routes to interesting work and useful new things in the world.

Whilst I might not be sure what exactly I’d like to be working on, I’d like 2019 to mean doing fewer things, and making more tangible progress on them.

It feels like a lot of the useful work I’ve done in 2018 was through bridging different sectors/disciplines, which is interesting and fun, but generally not what I’ve been paid for. It’s also not particularly the heart of what I think I am best at — unless there’s a specific goal in mind, a sense of forward progress in some way. It was good to wrap up the year with a conversation with Lou Woodley about these interstitial activities, the practices which are needed to do them, and what formal roles for this might look like (and the many names they might take) in different kinds of institution. People doing these are often “social entrepreneurs”, risk takers, pursuing a strange mix of grassroots and institutional activities, with a lot of interpersonal skills and communicating across boundaries, and unclear and uncertain resourcing. Some of the most impactful things I have done this year were mentioning an idea in a different context, asking a question that no one in an organisation had thought of, making an introduction over email. Only a very, very small number of these have become things I encounter often, reminding me that I was useful in a small catalytic way.

Perhaps Don Norman has been thinking along similar lines about linking things. In his annual books post:

This year I read quite a bit of non-fiction, something I’ve not done for quite some time. Standout books include:

I also made an effort to read science fiction from different cultures. (Doteveryone published an anthology of women’s science fiction, which is worth a look too). Asian and African science fiction short stories in particular were fascinating. The wildcard here would be Our Memory Like Dust, by my old colleague Gavin Chait, with a focus on solar power and inequality.

I guess next year I’ll be reading (or should be reading) more economics — Janeway, Ostrom, and so on.

Finally, four years ago I was leaving the Open Knowledge Foundation. I thought I had left it in fairly good shape and with the best prospects for strong leadership to take it forward — there was core funding, a lot of momentum, a big foundation supporting an executive search. Now Open Knowledge International starts a new year with a new CEO who is, hopefully, this time, the strong leader it needs for a new era of open. Good luck, Catherine.

One small part of the open knowledge world is the public domain of information. Every year, the public domain receives new works. Check out some of the 2019 highlights — such as “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” by Robert Frost.

I made a concerted effort in 2018 to work more in the open, blogging events and ideas, and also since September writing weeknotes. The weeknotes are a bit of a grab bag of things I’ve read or seen, conversations I’ve had, fragmentary bits of synthesis where there seems to be any. Publishing rough notes, without any serious thought about a reader (sorry), is a discipline which encourages me to put time into reflecting, which otherwise probably wouldn’t happen. You, dear imaginary reader, are a tool for personal accountability. It is an effort to write weeknotes; they take time. Reflection takes time, and with a set of part time jobs at present, only one of which is paying me to do anything like this (and then only partially), it’s good to have a reason to make myself step back a bit.

With yearnotes I suppose I am stepping back another level; possibly it would be worthwhile doing this more than annually, and perhaps about specific topics. One thing my weeknotes show clearly is that each week there are diverse topics catching my eye, and although I can probably sketch out a few recurring themes, they are all happening in parallel — and most of them are not topics I am actually working on, in a paid sense. There’s not been the clear blocks of time to synthesise any one of these strands, or sufficient bits of time to work through them with others, as I generally think better with others. These yearnotes are undoubtedly biased towards the last months of 2018, and especially to the reflective period of December. So they may not be a particularly good reflection of the year. They are very much like my weeknotes, a random collection of quickly typed notes.

One of the real highlights this year has been rich and fascinating encounters with people from humanities and social science, and their really different perspectives and ways of thinking and working. Just attending a history lecture is eye-opening if you’ve done most of your education in a scientific or technical field. Another good thing in 2018 was making time for random chats with diverse interesting people, even when there wasn’t a specific topic or purpose for the conversation; these have been super, inspiring and educational and useful in all kinds of ways. I’m going to make sure these keep happening in 2019, with contacts new and old, and including the very few people where it sometimes seems hard to get a conversation like this going.

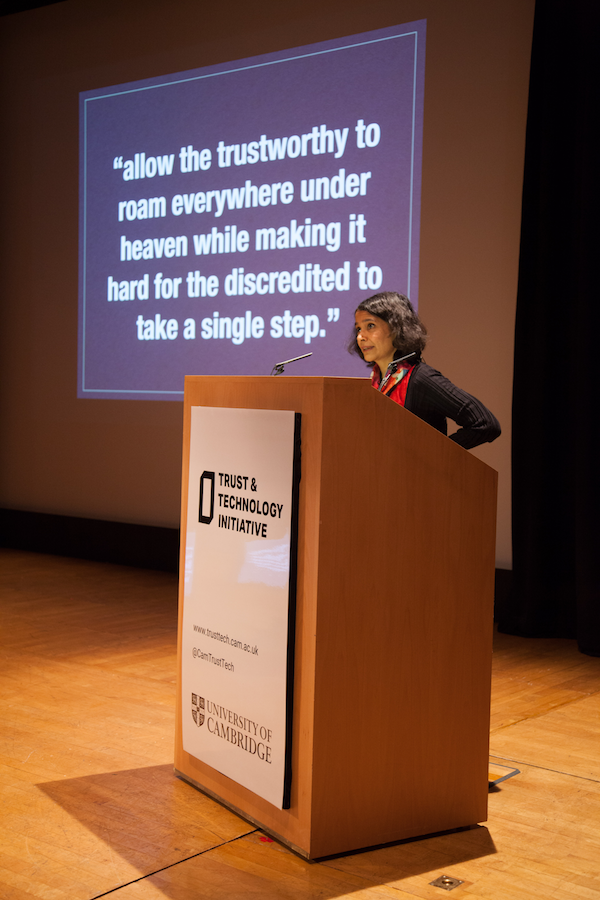

2018 felt like a year of treading water professionally, but I end it highly motivated to change that, which I guess is good. At the start of the year, I wanted to do more work with new technology, but opted instead to focus on capitalising on the pioneering work I’d been doing around responsible and ethical tech at Doteveryone, which was distinctive and ahead of the curve. Establishing the Trust & Technology Initiative at the University of Cambridgewas a great way to do this, and let me shape something focussed on the longer term questions around the internet, society and power which neither Doteveryone, nor the wider emerging “tech ethics” community are looking at. I’m really pleased we’ve created something distinctive and valuable, especially at a time when it would have been easy to follow the hype and the herd to fixate on artificial intelligence and data and very short term concerns. Instead of just critiquing the status quo — very easy this year, and not something we need a lot more of — we are thinking about how we can do better in the future. I’m also proud that we’ve identified how we can be most useful, in starting and supporting conversations that otherwise weren’t happening across disciplines and sectors.

|

| Malavika Jayaram speaking at the Trust &Technology Initiative launch |

|

| me speaking at Thingscon 2018 (credit: Thingscon) |

I had no idea, a year ago, that I’d be part of a team figuring out how to support change-making ventures in a new way. We launched the Impact Union this autumn, and it will be becoming a reality — a prototype at least — in 2019.

September was busy, with the Festival and the Trust & Technology Initiative launch, but once these were done and I’d divested myself of the time sink that was active involvement in the Digital Life Collective, I resolved to have more conversations about potential future projects, and with interesting people in general. I did pretty well at this and will continue to make time for random chats in 2019. Rather late, I also serendipitously found a way to catch up with the state of cutting edge technology as I’d originally hoped to do at the start of the year. With the departure of the previous research facilitator, who coordinated industry collaboration at the Computer Lab, an interim opportunity opened up to be more involved with the department. (Although the Trust & Technology Initiative is formally based there, most of our work is across the University at large.) It’s been lovely to be embedded in such an amazing computer science department, and, as I’m not in an academic post, to have the chance to catch up with what is going on across all the research groups and projects.

|

| View from the Computer Lab |

What did I think I was working on in 2018? It was July before I wrote something about this, trying to show how the various strands fitted together. Something about internet technologies, how we resource things (public and collective goods, such as open knowledge, but also the business models that enable services to operate), how they are owned/controlled (and therefore what risk capital is able to support their creation), and how we know what good looks like — what we measure and what it means.

That post mostly still applies, except for the bit about the Digital Life Collective. I should really have stopped putting time into this sooner — nothing much changed in the year up to my departure in September and the problems were clear from very early on. (I have not, as yet, set about creating the thing I hoped the Collective would be.) 2018 certainly saw the issues with the way we’ve been developing and deploying tech for a while reaching mainstream attention; in mid-2017 that seemed like it could still be a long way off. State action to deal with some aspects of surveillance capitalism, the attention economy and the level of irresponsible tech is certainly coming now, and many good people are working to make sure this is the thoughtful and appropriate regulation that’s needed. Doteveryone’s work on digital understanding, especially for leaders and decision-makers, looks very relevant and prescient.

More people have left Facebook. I still feel this is a fine thing to do, if it works for you, but mass departures are not the solution to the problems it has caused, and leaving such a socially useful platform is something not everyone is able to do. Small businesses need Facebook to reach their customers and markets; individuals and community groups rely on it for connection.

There’s still work to do in building viable alternatives, systems which offer useful connectivity and services, which are pragmatically designed, with new business models and ways of thinking about what is important for tech. Several events in 2018 were great for exploring ideas here — I’d particularly call out the Public Stack summit, OPEN 2018, and the BBC/Mozilla Healthy Public Service Internet workshop.

None of these have yet given me the sense of a viable project to work on though. The closest is Oli Sylvester-Bradley’s “planet” concept, or something similar, which I roughed out some ideas for. It still feels too big. I think we need to look smaller, at more local, relevant and appropriate technology. In humanitarian aid or development, no one would dream of proposing a tech solution which would work everywhere or scale to the whole planet, or even a set of countries. Local and appropriate technology is essential. So why do we persist with the Valley-style idea that we need to go big, or go home? More and more it feels like smaller services, doing something useful for a modest number of people and well designed for their needs, with connections to other systems if required, is a better way to go. Such things might be supported through revenue, rather than endless VC rounds, and be better matched to the investment markets in Europe, or in the UK in a presumably post-Brexit situation.

You need risk capital to do risky things, that might not work. Today’s “tech VC” which is so often about funding marketing, a rather different risk (and learning) than technical risk and the learning from trying to solve engineering problems. I still have to remind myself that what I think of as tech, and what I find interesting, is now called “deep tech” in the startup scene.

The discussions at our CRASSH research network, ostensibly about open intellectual property and emerging technologies (mostly ‘deep’ too!), have been excellent this year. I’m very aware that the topics we are picking at aren’t really about IP as much as the general question of how new technologies can be developed and can help tackle problems (especially in poorer countries), and specifically where money comes from to do this, and once developed, how such tools/products/systems can be sustained. We’re trying to double down on economics this year, but we aren’t yet sure if economics (in the scholarly sense) has the answers, so perhaps we’ll also try business studies. It feels like our question has shifted from the original: the guiding question of our research group will be the extent to which open technologies result in equitable sharing of knowledge and cognitive or technology justice. I would say we have a broader question, of the extent to which different methods of resourcing technology development and operation result in equitable sharing of knowledge and cognitive or technology justice. Open IP might be part of this, but it’s more than that.

It was also good at the end of the year to go back to Cameron Neylon’s 2017 paper on collective action and infrastructure. This also points to smaller groups or communities as being easier to create shared goods for. There’s also something which echoes the ‘next generation internet’ conversations, as well as questions of equity — the idea of designing for worst-case scenarios, not just following best-practice models. There will be threats and bad actors, and we should design with those in mind (those we can anticipate, at least).

The Festival of Maintenance has introduced me to people like David Edgerton, Lee Vinsel and Andy Russell, who have really challenged the way I’ve thought about technology. It’s not just the question about how much we, in rich countries, focus on innovation rather than operation and maintenance, and get (excessively?) excited about new things whilst forgetting about looking after stuff. It’s also about the way we think about how new technologies arise in the world, which ones get developed, and how, where and why they get applied to which problems. Being back in a University context (probably temporarily, again) reminds me of the dominant “tech transfer” narrative, of ideas incubated in academic departments, then transferred out (with IP, or people, or whatever) into the world of business (or perhaps into the poor world, now we have the Global Challenges Fund to support research which acts as overseas aid), where they are “scaled up” or “diffused.” I’m less convinced of this, now.

So, 2019. I’d like to be building something, working on a venture or challenging big project, using my problem-solving skills and working in a team, but what? There is a lot to do in internet technologies that people use every day, but despite encountering many projects over the last couple of years, nothing has stood out as the right place to put my energy. There are blockchain-ish projects, distributed/decentralised projects and so on, generally seeming notably flawed or impossible to understand in enough depth, sometimes due to proximity to the messy cryptocurrency hype or cults of personality. There will be new endeavours especially around distributed machine learning; hopefully some will actually deliver useful services, but I struggle to see meaningful value in most of these where people are concerned, simply because I am not sure we are measuring or optimising the right things. (Machine learning for technical systems, monitoring power infrastructure, say, or building structures, or network security — systems where there are sources of relevant and useful data and where it is clear what ‘good’ looks like — increasingly seem more viable to me.)

Maybe the ideas generation stuff needs more work. The exploratory events I mention above were great, but it felt like they needed just a little longer, more time to dive deeper, to enable more concrete ideas to emerge that there would be momentum to take forward. There’s still convening to be done, bringing together people from these slightly different worlds (open source, distributed systems, co-ops, design, etc), creating space and time for deeper constructive discussions. There needs to be some sort of framework, a guiding direction, some constraints; just waiting for “emergence” won’t help. (There’s been a great thread on nettime this week which critiques this, as well as some other ideas for an “Anthropocene Socialist” movement… and the Digital Life Collective experience also brought this home to me. Great intentions, but not enough structure or direction for any new growth to take hold. Ultimately, it comes down to a set of social issues — how do we collectively do things, whilst respecting different mindsets (such as introversion), emotional labour, and giving everyone a balance of challenging labour and rest?)

Pending a suitably connected and positioned organisation doing this convening, and in the absence of an idea and a team to work on a human-facing internet problem, tackling problems elsewhere seems more appealing. Increasingly I think that means looking at climate and sustainability stuff, and I have a sense that there’s more I could do to build on my previous experience around manufacturing and materials, and energy. These seem like they might be more fruitful routes to interesting work and useful new things in the world.

Whilst I might not be sure what exactly I’d like to be working on, I’d like 2019 to mean doing fewer things, and making more tangible progress on them.

It feels like a lot of the useful work I’ve done in 2018 was through bridging different sectors/disciplines, which is interesting and fun, but generally not what I’ve been paid for. It’s also not particularly the heart of what I think I am best at — unless there’s a specific goal in mind, a sense of forward progress in some way. It was good to wrap up the year with a conversation with Lou Woodley about these interstitial activities, the practices which are needed to do them, and what formal roles for this might look like (and the many names they might take) in different kinds of institution. People doing these are often “social entrepreneurs”, risk takers, pursuing a strange mix of grassroots and institutional activities, with a lot of interpersonal skills and communicating across boundaries, and unclear and uncertain resourcing. Some of the most impactful things I have done this year were mentioning an idea in a different context, asking a question that no one in an organisation had thought of, making an introduction over email. Only a very, very small number of these have become things I encounter often, reminding me that I was useful in a small catalytic way.

|

| Beer glass |

Perhaps Don Norman has been thinking along similar lines about linking things. In his annual books post:

Experts generalize, producing expensive solutions to the world’s problems, solutions that invariably fail. Everyday citizens tinker, developing low-cost efficient solutions. Moreover, solutions that they know how to operate and maintain…There’s value in both expertise and local, grassroots knowhow, though, and bridging between these might be the most critical thing. Lou is thinking about this mostly in terms of the new practices needed for science, as there is more science and complexity than ever before. There are new roles for sherpas, who guide and connect. Local communities might benefit from ideas and insights sourced from experts elsewhere, to create useful innovations which go beyond incremental changes, if we can find new ways to support effective links. (Field Ready’s work is perhaps an example of this). There may be much more open knowledge and information these days, but having the information out there is a very tiny proportion of the process to make a difference. There are many steps.

| |

| Gloknos launch event bookmarks |

This year I read quite a bit of non-fiction, something I’ve not done for quite some time. Standout books include:

- Everything for everyone — Nathan Schneider. In theory it’s about co-ops, in practice it’s a fascinating ramble through Occupy, technology, and more.

- Shock of the old — David Edgerton. I’m going to be recommending this to all the folks I know who work in tech or innovation. David challenges how we think about technology, invention and innovation, and what matters most in these areas.

- How Democracy Ends — David Runciman. A clear perspective, sadly with no strong ideas for the future.

- Junkyard Planet — Adam Minter. Insights into where waste goes and what happens to it.

- Poorly Made in China — Paul Midler. An insider view of how Chinese manufacturing works (not particularly about tech).

- (started but not finished) Winners Take All — Anand Giridharadas. Thanks to Martha for the recommendation!

I also made an effort to read science fiction from different cultures. (Doteveryone published an anthology of women’s science fiction, which is worth a look too). Asian and African science fiction short stories in particular were fascinating. The wildcard here would be Our Memory Like Dust, by my old colleague Gavin Chait, with a focus on solar power and inequality.

I guess next year I’ll be reading (or should be reading) more economics — Janeway, Ostrom, and so on.

Finally, four years ago I was leaving the Open Knowledge Foundation. I thought I had left it in fairly good shape and with the best prospects for strong leadership to take it forward — there was core funding, a lot of momentum, a big foundation supporting an executive search. Now Open Knowledge International starts a new year with a new CEO who is, hopefully, this time, the strong leader it needs for a new era of open. Good luck, Catherine.

One small part of the open knowledge world is the public domain of information. Every year, the public domain receives new works. Check out some of the 2019 highlights — such as “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” by Robert Frost.