weeknotes: technological terroir

I was in San Francisco this week, for a mix of meetings and the Partnership on AI’s annual all partner event, representing Doteveryone. A year ago in Berlin much was made of the importance of balance between industry and civil society voices, with half for-profit and half non-profit representation. This seems to have shifted somewhat, with civil society feeling very much in the minority (although there were plenty of academics present, the scholarly research community is not the same as that representing wider society). Also a useful reminder in one conversation with an industry person that ‘civil society’ isn’t always a useful term — they understood it to mean government and regulators.

This trip meant I missed the ExtinctionRebellion protests in London, blocking bridges on the Thames to call for government action on climate change.

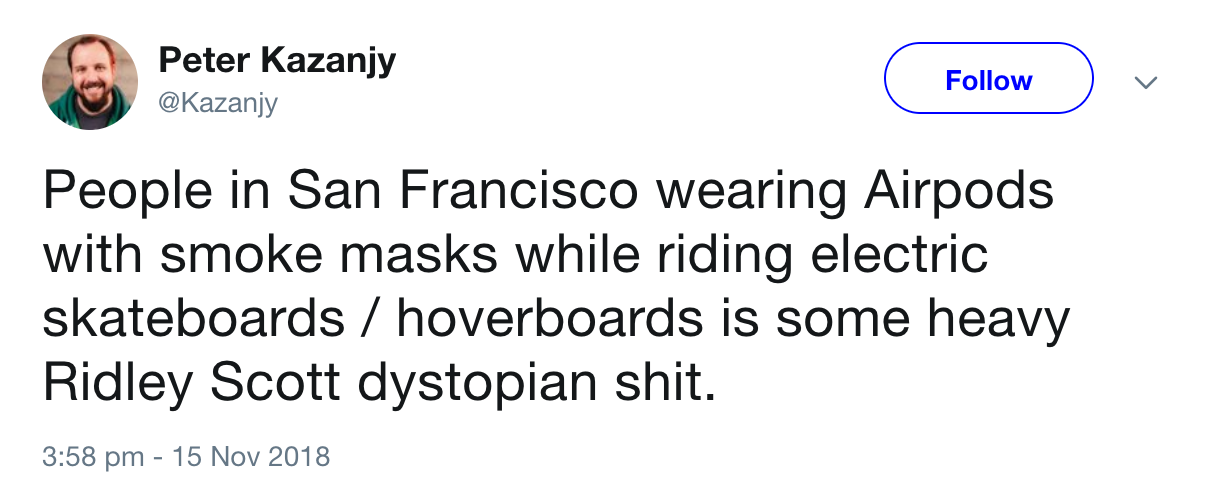

San Francisco was smoky — to look at, anyway; whatever pollution was in the air wasn’t something you could smell. Also, a great density of electric scooters, whizzing along the roads, cycle lanes, and sidewalks (where they were also often piled up stationary too).

It was great to meet Jesse Kriss (of Ragtag, who support technologists getting involved in progressive organising) for a wideranging chat. Jesse co-created listenup.tech — a series of online conversations to help techies hear and learn from critical voices from outside the tech industry bubble. (I wonder how much traction they are getting — and forgot to ask.) He recommended this talk and transcript, a whistlestop tour of issues and projects about the rich world and the poor world, technology, climate, and the importance of relationships.

Doteveryone is building out our network in the US around our mission to make the tech industry more responsible and accountable, for the good of everyone in society. So many of the conversations we had were to learn about the state of tech businesses, awareness of ethics and responsibility issues, and to think about how we might need to adapt our mostly UK activities to date to this context. Intuitively, it feels to me like the UK is ahead of Silicon Valley in terms of responsibility, and ‘tech ethics,’ although I don’t have much data.

It was interesting in this light to read this:

I propose thinking about whether there is such a thing as “technological terroir.” Just as local differences between wines and cheeses are studied, sought after, and even cultivated, might the same be true of technology?

in Anthropology News. The example is LA -

At the same time, I was puzzled that these artists, producers, and brand ambassadors — all pursuits I had naively placed outside of technological work — took pride, through their VR work, in being “women in tech.” This gave me pause, as it didn’t match what I thought it meant to “be in tech.” But I now interpret from these affiliations that “technology” is something ontologically different here [in LA]. Technology is not strictly programming or engineering, but it encompasses working with — storytelling with — emerging tools.

Similar to the women in tech I’ve often met at meetups in London, who are women in marketing, in HR — in tech firms. It also reminds me that I feel like I am an engineer who works with internet systems; I’m increasingly unsure how I relate to “tech” stuff, the advertising and media businesses that count as technology in so many contexts.

The idea of technology terroir is a useful one, as it captures all kinds of differences in culture, skills, attitudes, business and industry profile. It is perhaps richer than the idea of “clusters” which UK tech policy seems to use. I can see terroir in how Cambridge, London and Brighton tech scenes vary.

Thanks to Sentiers for this one.

I continue to ponder what might be better measures for new technologies.

Talking to one Valley engineer, they described how the cancellation process for their service has been made easy and frictionless, even though they have no direct evidence of the benefit of this. You don’t get great metrics from a smooth cancellation system— it’s a decrease in user numbers, and you can’t tell whether a more tricky process might stop some of them from leaving. But indirectly, from interviews with customers past and present, there’s a sense that not annoying them when they leave means they do sometimes come back, and they are left with a better feeling about the company and service. A rare example of a tech firm doing something not directly linked to an obvious performance indicator, which goes against some thinking about user growth. Customer benefit, without measurableness. Are there other examples of this?

I met Catherine Bracy, now at the TechEquity Collaborative, near Uptown Station, which was bought and redeveloped by Uber as a new office complex, before they sold it last year, perhaps partly because of strong push back from the local community. She posed the question: what would it take for it to be a real positive thing for locals when a big tech company moves to your area? Maybe there’s something usefully measurable in there.

Nick Stenning wrote a Twitter thread this weekend about the tensions between good software engineering practice (testing, code review, etc), and good business sense (shipping quickly, getting market share). This leads to inevitable strain between the business needs as a whole, and the needs of the engineering team (tomorrow, dealing with tech debt, as well as today). This sort of thing has come up in developing the ideas of responsible technology development in recent years; responsible, and/or ethical development, often means going a little slower. The internal business tensions aren’t ones I’ve thought about in detail, other than thinking about the power of engineering teams to influence their overall business. (I’ve been sceptical about the power of individual tech workers to effect ethical process in businesses. The protests and resignations over Google Maven this year suggest that in some cases I was wrong, but Maven was a clear project with obvious implications for personal morality, and an extremely privileged workforce in a region with many other similar roles and exceptionally competitive pay.)

From Stratechery (an unusual newsletter which I actually pay to subscribe to, although I’m yet to decide whether I feel it’s worth the money) -

Culture is not something that begets success, rather, it is a product of it. All companies start with the espoused beliefs and values of their founder(s), but until those beliefs and values are proven correct and successful they are open to debate and change. If, though, they lead to real sustained success, then those values and beliefs slip from the conscious to the unconscious, and it is this transformation that allows companies to maintain the “secret sauce” that drove their initial success even as they scale. The founder no longer needs to espouse his or her beliefs and values to the 10,000th employee; every single person already in the company will do just that, in every decision they make, big or small.

So if the founder’s values deliver good business growth on conventional ‘digital’ metrics such as user numbers, they become/are intrinsic to how the company works, and very hard to change. Good if those values are also working for people, communities and systems outside the company; less good if the company is Facebook, maybe.

And so to Nathan Schneider’s new paper on Cooperative Enterprise as an Antimonopoly Strategy, containing interesting insights into cooperative mechanisms and how they might help with antitrust issues.

Hidden Forces may be an exception to my observation that many podcasts have low signal to noise ratios. This week, an excellent example, with Bill Janeway on capitalism and funding innovation. Who pays for innovation and invention? Bill describes the way government and private sector investment interplayed around the internet, and the (correct) frustration of regular folks with the tech world, and the loss of trust in the state. Also touching on climate change, the social impact of the US war on drugs, the focus since 2008 on the “unicorn bubble” and growing the digital space, and distributed ledgers and ICOs. Low interest rates have driven not just venture capitalists, but also institutional investors, to buy securities in unicorns or potential unicorns which are illiquid private companies (which may well fail). Fear of missing out is “overcoming basic common sense”, in this, and it leads to founders being granted a lot of power — possibly a disproportionate amount — in order to try to be ‘the next Google.’

The US has done a bad job of buffering its constituents from the disruption of the tech revolution, which it created.

Bill seems to find optimism in that not only can the state mess up innovation, but we’ve seen markets can screw themselves up too :) The 2008 crisis and subsequent long recession have been gifts that keep on giving to academic economic and financial disciplines, forcing them together, inducing a shift to real, deep empirical work (instead of theorising on models), and so on. A key point being that with this sense that markets will sometimes fail, meaning there is an essential role for government in ensuring the availability of jobs and incomes on a broad and fair basis.

Azeem Azhar in Exponential View includes an end note on “small-t technology”.

Small-t technology is technology as defined by the wonderful W. Brian Arthur, “a means to fulfill a human purpose”. And technology should be a humanistic, progressive, diverse, inclusive arena which uses the tools of curiosity, observation, cultural interaction, and the scientific method to “fulfill a human purpose.” Small-t technology is part of everyday life. It is the smallest tweaks in code, organisation, social behaviour, widgets, practice, communication that feed into the economy and our groups. …

But small-t technology is often confused with Big-T Tech, or just bigtech.

The real (and exaggerated) misbehaviour, stubbornness and obnoxiousness of many the individuals in the Big-T Tech industry (execs at Facebook, Google, Twitter and beyond, and their firms in toto) might spill over into a general diminution of faith in small-t technology.

Whilst I agree that there are issues to tackle around power in bigtech, and different issues in small-t technology, I’m not sure “small-t” is a helpful name here. Some of today’s bigtech claimed to be small-t tech once, in the form of small companies with modest numbers of users — doing things like “connecting the world”.

We need to apply our technologies where we can at appropriate scale, without being forced to ‘dominate the market’ or be ‘global’ simply in order to secure the resource to get started at all. Small pieces, loosely joined — better for code, and for resilience, and for serving specific needs in specific communities. Hence my interest in funding for emerging technologies, and the ownership and incentive structures required.

Not everything needs the exponential, hockey-stick growth so beloved in Silicon Valley, and the obsession with metrics and KPIs (key performance indicators) every quarter. These are troublesome both for responsible development of technologies which might aspire to be Azeem’s bigtech, and for the tech for good space, where navigating the complex social, political, economic and technical landscapes makes going from a pilot stage to something larger and replicable incredibly hard. (If you are going through that, apply to the Impact Union — it’s exactly this tough phase which we want to support purpose-driven entrepreneurs through.)

Responsibly building appropriate technologies to solve significant problems, without driving for profit and growth at all costs, won’t be for everyone. It’s not realistic to imagine that we can get all tech businesses to be responsible — there will always be criminals, scammers and wide boys. But perhaps we can shift the balance, by supporting better culture in tech businesses, and making it easier to measure what good looks like for things other than growth in users and in attention.

Azeem concludes:

So, we need two different strategies: one to tackle the power, where it distorts, of bigtech, and another to critically evaluate, steer and design the direction of small-t technology and the system within which it operates.

Critical evaluation of tech for good is hard, because projects are trying to do something good in a challenging environment. That doesn’t mean they get everything right in terms of ethics and good practice though, even allowing for the need to move quickly (as Nick mentions — the need to deliver applies just as much to non-profit technologies tackling important challenges). People with expertise in the challenges, such as education or energy, don’t always know which bits of technology, of technology development practice/process, and of tech metrics, should be adopted for their projects, either.

Incentives and metrics really matter. From Wired’s great article on NotPetya,

In 2016, one group of IT executives had pushed for a preemptive security redesign of Maersk’s entire global network. They called attention to Maersk’s less-than-perfect software patching, outdated operating systems, and above all insufficient network segmentation. That last vulnerability in particular, they warned, could allow malware with access to one part of the network to spread wildly beyond its initial foothold, exactly as NotPetya would the next year.

The security revamp was green-lit and budgeted. But its success was never made a so-called key performance indicator for Maersk’s most senior IT overseers, so implementing it wouldn’t contribute to their bonuses. They never carried the security makeover forward.

Security is just yet another externality that today’s corporate quarterly indicators don’t really address.