Launching the Trust & Technology Initiative

Last week was the launch of the Trust & Technology Initiative at the University of Cambridge.

I talked briefly about the ways technology forms part of wider systems, and some of my hopes for the initiative. Here’s my (rough, rather last minute) talk.

We build the technology we can imagine — such as what we see in our science fiction.

One of my very earliest projects at AT&T Labs was prototyping a Star Trek communicator style badge. My boss was a big Trekkie. You hit the badge, it recorded 30 seconds of video, so you could capture an introduction with someone, and get a reminder later of who they were, their face, what they said about themselves.

I wish I had one today — there’s a lot of you and I’m bad at remembering names and faces.

(If you’re wondering about the data privacy issues there, this was nearly 20 years ago, we thought very differently then. We never imagined these clips would go outside one’s personal, secure systems.)

You may also wonder why I don’t have that badge. Useful technology does not always get out into the world. Aside from whether we could have found a business model that would have allowed us to secure investment to develop and manufacture the badges, our research unit was closed in the dotcom crash — remember that? — and the intellectual property didn’t leave with the team.

Technology does not exist in isolation. In how it is designed, made, deployed, maintained, and decommissioned, it is always part of larger systems. Those might be technical systems — supply chains, networks — or human systems. We need to think not just of users, or those around them (for instance, the family members who are so often ignored in the design of apps and connected home systems), but beyond that. Think of those who make and assemble our electronics, for instance, or who pick up the phone to try to help us when we have problems with technology. Think of those who are on call nights and weekends, looking after the software systems that keep our world running.

“Technology” for the Trust & Technology Initiative includes many things; we talk about internet technologies, or computer technologies, or ICT. It’s more than that — to give you a flavour — from email to machine learning to cyberphysical systems, robots and autonomous vehicles, mobile apps and distributed sensor networks, satellite mapping…

Technology isn’t just software, or computer hardware. It’s data and information and the systems around them. Trust in information is important to us to. How do you know what information is trustworthy?

The Initiative thinks about technology used by people in their roles as citizens, workers, learners, consumers, family members; by businesses, by the media, by governments, by civil society and activists, and by criminals. By rich people, and by poor people. Computers in our hands, computers in data centres (the cloud — “someone else’s computer”, as they say), computers distributed across networks. Here in the UK and in Western societies, and in the global South; in remote areas, and in megacities.

The way technology is developed has rightly come into question.

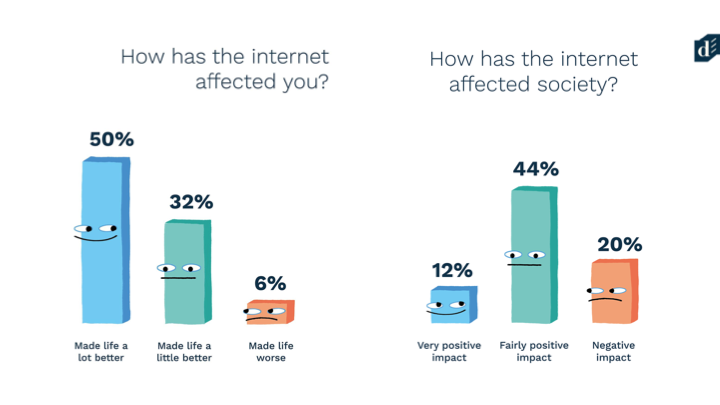

I also work at Doteveryone, a think tank, and this year we did a representative survey of the UK population about how they feel about technology. The results show that people feel they’ve benefited from the internet, individually, but they also feel it’s had a negative impact on society.

We often neglect this bigger picture — or focus on a trivial version of it, like “do no evil” or “Transportation as reliable as running water.” It’s easier in tech design — comparatively — to think about individual user needs.

Different societies and cultures, around the world, will have different values, and their attitudes to technology and expectations of it change over time.

Technology is not neutral. It is developed by people, with individual perspectives, from different cultures. It is developed by organisations, with business models and incentive structures, that drive what is done.

We are starting to see where yesterday and today’s incentives take us, with the “Big Tech” back lash.

Let’s look at the issues we’re seeing there — they are consumer concerns, around personal data, privacy, hate speech, distorted messaging, worries about machine learning, fairness and automation of jobs and vehicles. Plus the rapid growth of tech companies who play fast and loose, at the very least, with the law.

At heart, really, all these concerns are about power. The power of a small set of corporations.

Problems like these hit the most vulnerable first. We don’t always hear their voices. Domestic abusers using phones, computers and connected devices in the home to control and intimidate. Machine bias in the US justice system. Workforce automation — not robots replacing jobs, but workers in warehouses and factories who are monitored digitally for performance, with no choice. Ending up wearing adult nappies so they don’t have to take even a toilet break.

The seemingly inhuman business and government choices that enable these things do not build trust in technology, or those who make it.

Not that more trust is necessarily good.

Sometimes we should distrust technology, ask questions about it, use it critically and cautiously if at all, hold those who provide it to account.

Do not mistake use for trust. Companies like to measure use, it’s easy to count how many users you have. I was at an event last year where everyone seemed to agree that the Amazon Echo is listening all the time, and reporting back everything it hears to Amazon. Nonetheless, around half those there had an Echo in their home. They don’t trust it, though. They use it to play music or run kitchen timers — as an aside, what a waste of a capable underlying system!

(For the techies out there who may have confidence that this isn’t the case, that the Echo is not always listening — how would you persuade someone that this is the case? There are levels of complexity and opacity that would are hard to grasp even for many computer scientists.)

Trust is nuanced, and contextual. It’s not binary.

It’s also not just business. I might file my taxes on a government website, it doesn’t mean I trust the government. Or the website.

We’ve been lucky, in some ways, that the troubles that have caused the tech backlash have not been about security or safety. Just data, still an abstract idea for many people.

The market doesn’t reward security, and we’ll need policy change to change the market dynamics.

And maybe we need new ways of thinking beyond that.

Take resilience. We’ve optimised so long for cost and efficiency that we’ve made very fragile systems. Last year, NotPetya, a ransomware attack, took out huge swathes of public and private sector systems; multiple companies were left with 9 figure costs, such as Maersk, the shipping group. We didn’t hear much about this — companies generally don’t want to admit such challenges. Another example — NotPetya also took out Nuance, the voice to text transcription service, with a near monopoly in the market, for protracted stretches. Nuance is used by doctors in hospitals in the US, and these outages lead to delays and degraded patient care (and note this was not a direct attack on hospital systems).

Resilience, and safety and security. We need to think more and work on this.

Through the tech backlash, there is attention on these data issues, and it’s good to see that there is some response; we have GDPR (we’ll see how that works out) and many new initiatives and centres looking at data, society, ethics. There is an understandable tendency to focus on immediate concerns, and much talk of ‘tech ethics’ as individual responsibility, of education, and so on.

These are all valuable contributions, but incremental.

The ethical fixes possible within an existing business, with rich and complex technical supply chains and consumers, with an established business model and incentive system, are perhaps limited.

The Trust & Technology Initiative will be looking at questions of power and accountability, at the more structural issues which frame the way we develop and deploy technology. Things which affect resilience, safety and security, sustainability, equality.

If we look 5–10 years ahead, we need to do more than, as software developers say, ‘patch’ the system. We need more radical ideas — to inspire us if nothing else. Ways to change the structures in which tech is developed more fundamentally.

The network of researchers around the trust and technology initiative will be looking at how we design future systems, recognising tech is not neutral and considering how technology and human systems are linked and integrated.

Personally I’m particularly excited to look at the potential role of the commons and the public sector in next generation technologies — new business models; new forms of ownership and control. Better places I can build tech in the future!

I’m also keen that we look at what we measure. Organisations build things to deliver on their metrics; what they can measure and what they do measure drive what happens. In silicon valley that’s things like user growth, or activity on a platform. Metrics in all kinds of contexts miss critical human elements. How can we prioritise human experience, individually and collectively, and work towards that, just as we do a technical performance measurement?

To build tomorrow’s technologies better than today’s, we need systems thinkers, and people who can bridge between disciplines and between sectors. That’s why the Trust & Technology Initiative is so important — connecting people and finding ways to build bridges is a key part of what we do. We kickstart new conversations and support researchers working on new ideas, both within Cambridge and in collaboration with others.

Technology has the potential to support the real needs and wants of people, communities and societies, not just creating what a few tech companies want.

So at the Initiative, we’re not examining the status quo of tech today, as much as working out how we can build better in the future.

Not building technology better, but building systems better, thinking holistically about markets and ecosystems and people and the wider contexts.

In the breaks today, have conversations you don’t usually have, maybe with people you don’t usually meet. There’s folks here from a really diverse range of sectors, disciplines.

This is just the start of what we hope will be many valuable discussions and collaborations in the years to come.

Thank you.