The first Festival of Maintenance

This article was originally posted over on Maker Assembly. Reposting here with permission. Deeply grateful for Maker Assembly’s encouragement and support of the Festival!

I was inspired to create the Festival of Maintenance last December during the Maker Assembly Summit.

The Summit brought together a community of people interested in critical discussion about maker culture: its meaning, politics, history and future. We talked about how a lot of maker culture is about making new things, and in many Western contexts, that’s making gadgets and gizmos that are fun for a while but generally then gather dust until eventually thrown away. The Summit also discussed the sustainability of makerspaces, and how they are maintained past initial capital and enthusiasm; local manufacturing, and the unrealised potential for repair, reuse and recycling. These issues lead us to think about business and capital models, and their relationship to sustaining systems and maintenance, and about the culture of looking after things vs making new ones. You can read my reflections on the Summit here.

There are amazing individuals and projects striving to maintain, to repair, to reuse, to sustain, to steward, to remanufacture and to recycle things of value — hardware, software, data, infrastructure, communities. They work in the public sector, the private sector, at charities and non-profits, as volunteers, in co-ops and collectives. Too often, they are invisible to those who benefit from their work. From the Maker Assembly Summit conversations, some of us felt we should celebrate maintainers, learn from the different forms and practices of maintenance, and the ways organisations are finding to support these, and figure out how to build and manufacture more sustainable products and systems — because some of the most important activities in the coming decades will need to bring together the physical and digital and social.

Following these conversations, a group of us set out to organise a Festival of Maintenance, and on Saturday 22nd September, it happened!

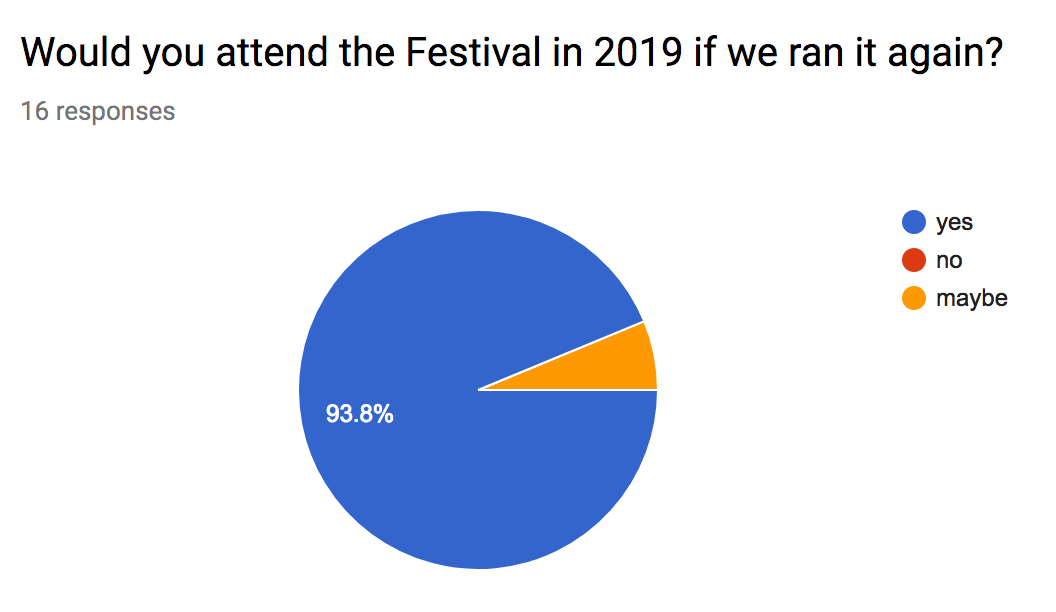

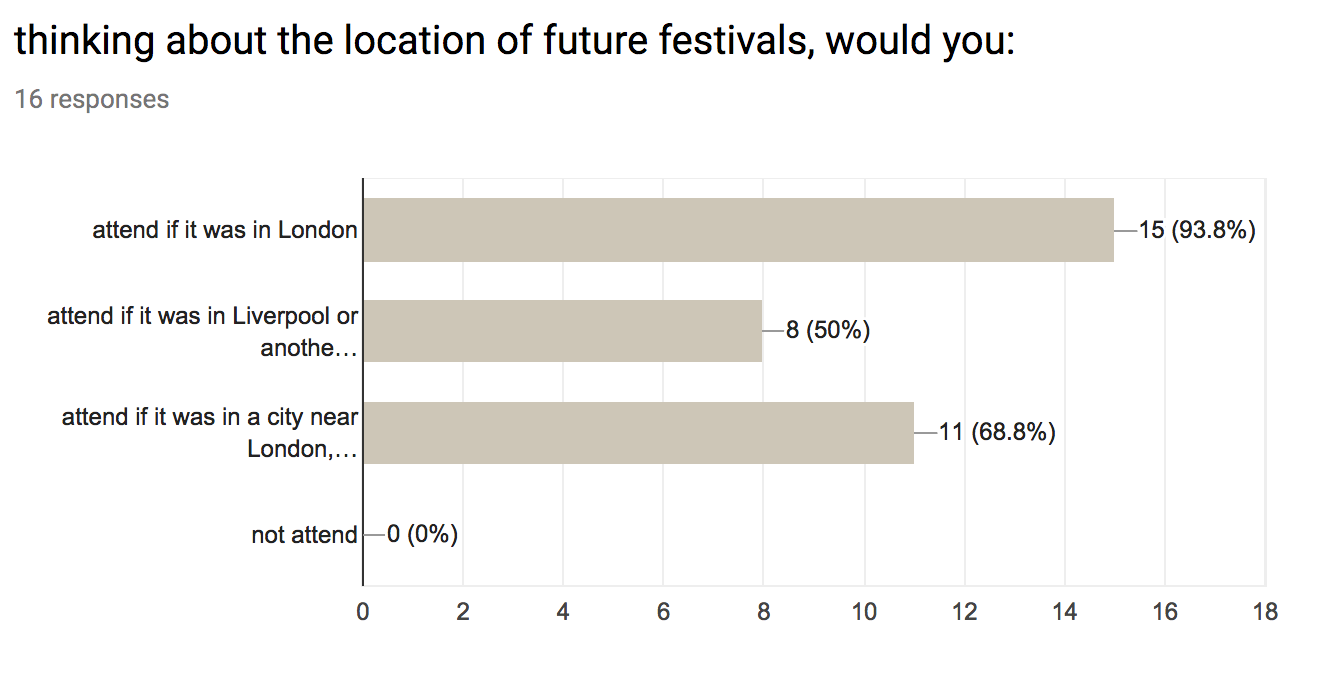

If you like this sort of thing, follow us on Twitter, or sign up for very occasional email updates. It went well, and I rather think we’ll do it again :)

Read on for a summary of the day, audience feedback, and details of where Festival funds came from and what they were spent on. You can also follow #Maintain2018 and listen to audio recordings of the sessions.

The first session was a set of provocations around the nature of maintenance and where it fits in our world.

Simon Elmer from Architects for Social Housing shared a great data-driven investigation into the relative costs of rebuilding and refurbishing social housing in London — and the side effects of these choices.

Natalie Kane, curator of digital design at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and one-half of research project Haunted Machines, on how we both maintain our bodies, and deliver the performance expected in some roles (in space, or in warehouse/factory work), using adult nappies.

Alanna Irving talked about different facets of leadership, and the need to balance visionary with operational leadership within a team. A subject close to my heart! Alanna touched on the hidden and challenging labour which makes big visionary ideas a reality, and the need for empathy in both directions — both from visionary to operational leaders and vice versa. You can watch Alanna’s talk here — she joined us live from New Zealand for Q&A.

The next session was about what has happened to maintenance, and its status.

David Edgerton, author of Shock of the Old (highly recommended!) gave a great talk about the ways we think about technology and maintainers. Maintenance work can be routine — or highly skilled. Maintaining things can be harder than making them; but then an old jet engine, seemingly more worn and in need of care, may take less time to maintain than a new one, as the maintainers have learned how to do it. Historically, engineers mostly worked on repairing things, keeping them safe, whereas today they want to present themselves as creatives, disruptors.

David had a political point about the criticality of maintenance in a society, and what that means for the way the society is managed; despotic governments which ensure maintenance is carried out might be justifiable if a society is at great risk otherwise. He touched on our cultural focus on innovation and entrepreneurship — which is often imitation, not real innovation. We often overlook material things; but perhaps Brexit is changing that, as we recognise the importance of supply chains for food and energy. The Chequers proposal separating regulation of goods and services illustrates the disconnect of the current government from reality — people who know about real business, and maintenance, recognise that goods and services are inseparable now.

Hazel Forsyth from the Museum of London took us back to 1500–1750, for a look at repair and reuse across buildings, documents, garments and precious metals.

Alex Mecklenburg drew beautiful parallels between maintenance in stories — and in the work of creative agencies in marketing and advertising. Once you’ve slain the dragon, who is going to look after that huge castle? Alex talked about her enjoyment of stories which describe everyday living as well as adventures, and the frustrations of work in agencies where short lived heroics get the attention, when steady ongoing customer relationship maintenance is essential.

Creativity and maintenance go hand in hand. And in a mature ecosystem as much energy goes to maintenance as goes to creativity. — Gary Snyder

Mike Green, Chairman of the Central London Maintenance Association, explained the incredible scale of facilities management and the amount of maintenance that goes into it — maybe 5% of GDP. The CLMA was created when new technology started to change the sector in the 1960s; and now it’s reinventing itself to do the same as the internet transforms the work again. It seeks to support practitioners to understand and work with new tech, when the professional bodies can’t keep pace. Maintenance is much less “shit and grit” and more about monitoring, preventative activities, managing energy — maintainers with laptops tracking all kinds of information.

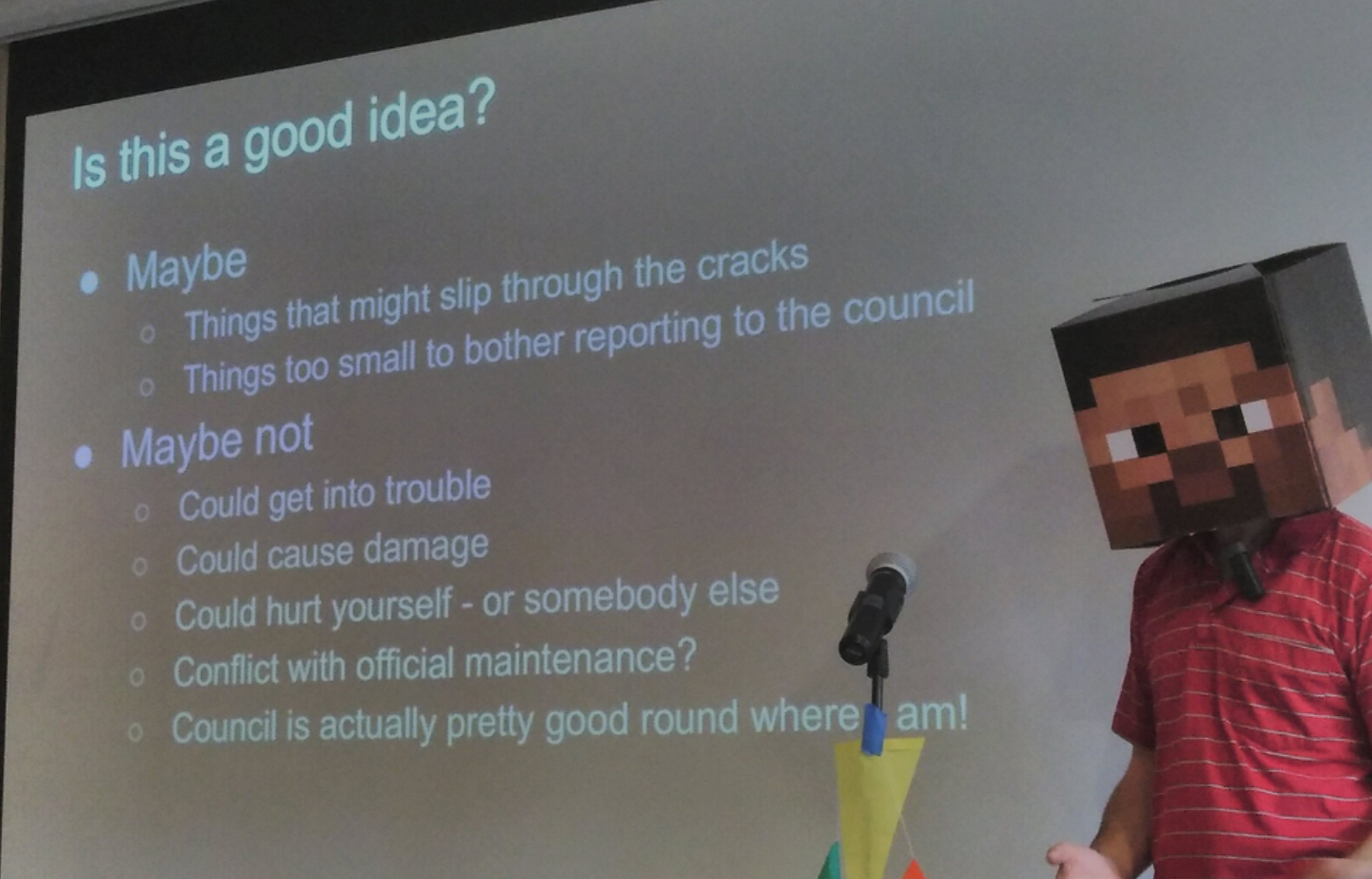

After lunch, I was delighted that the Guerrilla Groundsman, a real local hero, could join us incognito to share reflections on random acts of tidying and maintenance in public spaces in Cambridge.

Read about his work fixing benches, cleaning signs, painting bollards, and even checking the typefaces and moulding on street name signs to retain original designs when repairing them.

We moved on to a session about communities involved in maintenance, and the maintenance of such communities themselves.

The afternoon sessions brought in more ideas and speakers related to the maker movement and makerspaces, which had played a big role in inspiring the Festival in the first place.

Adrian McEwen from DoES Liverpool talked about how to organise the work of fixing and improving things in a volunteer community. If you mention something that’s broken, it’s easy for folks to respond “well volunteered!” — discouraging people from highlighting problems. DoES have developed a “Somebody should” list, which tracks things that need to get done and when they are fixed. This also recognises the labour of maintenance, as you can see who did something, and also builds knowledge of how things were fixed.

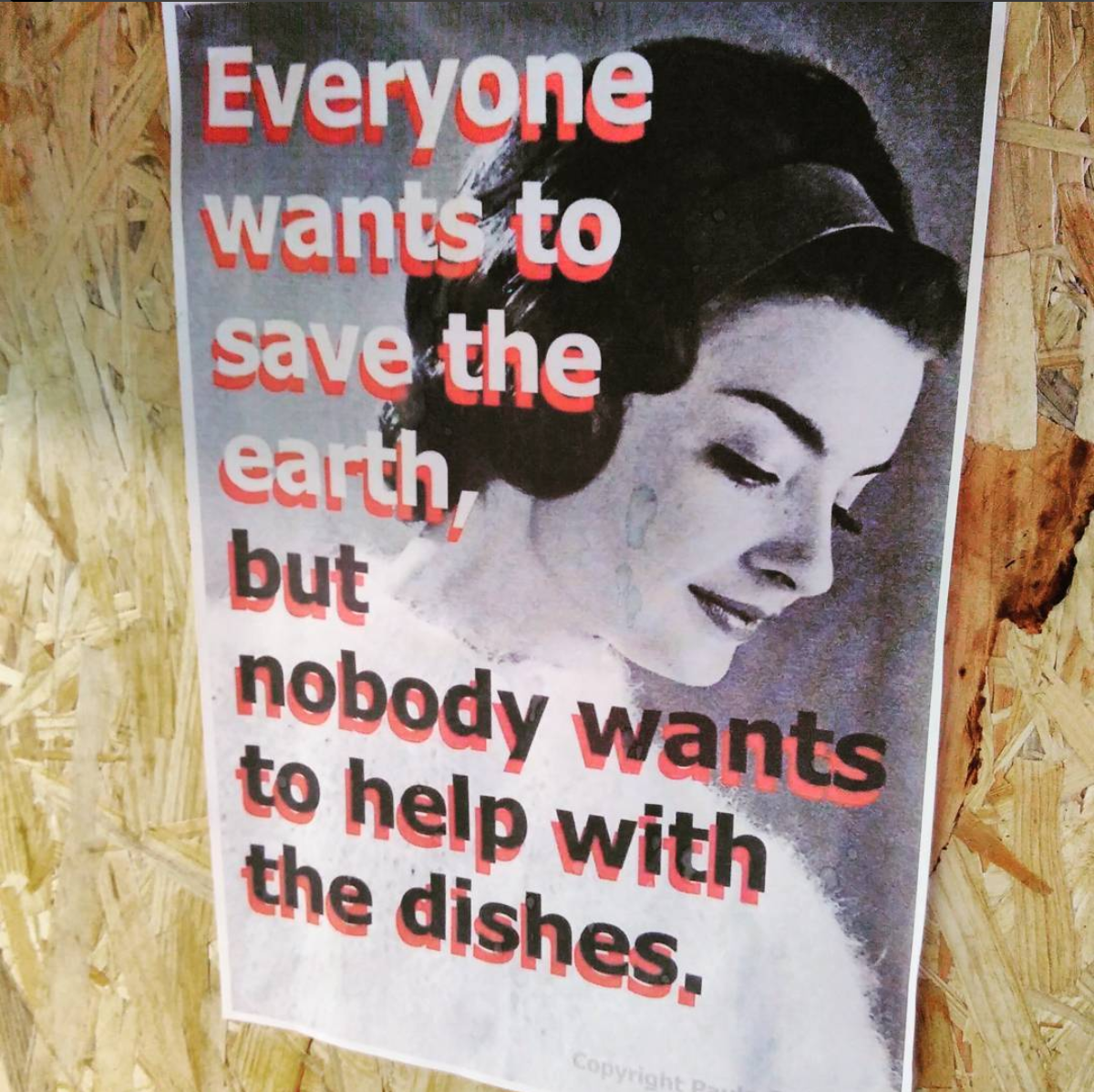

Adrian reminded me of a photo I took in a community space in Istanbul. It’s a P J O’Rourke quote, and both fits with this local community context, and broader spheres of tech entrepreneurship and change-making.

Oliver Holtaway helped to make Bath City FC a community-owned football club, and talked about what’s happened since that initial project, now the community have to maintain the club. There’s been a lot of innovation, especially around the model and creating democratic procedures, which create maintenance obligations around governance. Oliver also talked about the challenge of understanding the motivations of different kinds of volunteers — creative folks doing specific tasks are easier to understand and motivate, maybe, than those doing more maintenance-type work.

Lauren Hutchinson talked about the dangers of burnout and bullying, and the often-thankless emotional labour in volunteer communities. Maintaining shared goods and communities is exhausting, and when stuff goes wrong problems often snowball, and the pressure can fall disproportionately on a small group or individual. If the community isn’t just where you volunteer, but is your friends, your social support network, your workplace, stepping away is a big sacrifice. It was an important talk about mental health and looking after yourself as well as maintaining the collective goods and community.

The next session looked at maintenance in digital technology — looking after shared public knowledge, and enabling the infrastructure of the internet to be maintained by tending the documents that explain it for software developers.

Daria Cybulska from Wikimedia UK talked about how Wikipedia in English is growing, but the community of editors and contributors is not. Making it possible for more people to contribute is a challenge in both culture and process.

Chris Mills talked about the work of the MDN writers’ team at Mozilla, maintaining open standards, and the open web. Openness makes it easier to do things, and to maintain things. There’s a lot to maintain at Mozilla and in the open source documentation space though!

Our next highlight was a remote talk by Lee Vinsel, creator of The Maintainersin America. The papers from this conference and the articles linked to it helped us explore questions of maintenance through 2018 and we’ve been highlighting this and similar work through the #maintenanceinspiration hashtag on twitter.

Lee talked about how unhelpful ways of thinking and talking about innovation lead us to neglect maintenance and maintainers. Innovation isn’t always a good thing — and tech is not the same as innovation, either. We overlook the criticality of infrastructure, and the nature of the labour, status, identity and inequalities relating to maintainers.

Lee’s tagline is — How maintainers, bureaucrats, standards engineers and introverts created technologies that kind of work most of the time. :)

Our final session looked at new paradigms around maintenance, and novel ways people are supporting and enabling maintenance.

Chris Hellawell, founder of Edinburgh Tool Library, talked about affordable access to tools, but also the ways that tools can bring people together, through learning about tools and how to use them, working with others to fix things together. (An echo of the common makerspace idea that folks “come for the tools, stay for the community.”)

Jake Harries from Access Space in Sheffield talked about their work to support local people with technology, and how this has changed as technologies evolve. Fixing up old computers with Linux was well received, until smartphones took over. Now they are looking at digital fabrication

Janet Gunter, co-founder of The Restart Project which promotes community repair of electronics, discussed what needs to change for us to dismantle the 50m ton e-waste mountain. Restart have a campaign running and are part of International Repair Day which is on the 20th October this year. It’s important to both work on everyday repairs, and to engage in this wider policy and political debate, because forces are assembling to prevent repair, by demanding only authorised folks can do repair, by deeming spare parts ‘counterfeits’ and so on. Not everyone wants repair and reuse to be possible.

A huge thank you to all our speakers!

Many thanks to Maker Assembly and Maintain Our Heritage for their support. Thanks to all the volunteer team — especially Naomi Turner for wrangling speakers, schedule and venue, Jackie Pease for fighting camera gear so we weren’t so London-centric and Liverpool could take part too, Calen Cole and Marc Barto for keeping the event schedule on track and looking after attendees; plus Hwa Young Jung for our lovely logo design, Tati for the website, Michael Ball for domain support, Michael Dales for photography, and all the others who have helped with advice and guidance and ideas along the way (especially Andrew Back).

We’ve got a lot of speakers on our wishlist who couldn’t join this year, or who were suggested after our programme was finalised, so we could definitely do another day in 2019 and cover a similarly diverse range of topics.

Here are some of the things people said about the Festival:

The Festival of Maintenance made me happy to realise there were so many different types of maintainers out there.

A wonderful little festival, full of fascinating speakers and ideas

A mind opening festival, where people discuss the aspects of work and life that are too often overlooked. I feel inspired to maintain things!

The ubiquity of the innovation vs maintenance question meant an incredibly diverse range of speakers and attendees, it was really well done.

Maintaining the maintainers provides a really special moment of reflection on modern era’s fascination with the new at the expense of the existing. Relevant for anyone who is tired of hearing about innovation and wants to support the existing to make it better.

The conference was a stimulating experience, demonstrating how the concept of maintenance faces major issues across a whole range of sectors.

Loved meeting people that were so far removed from my day to day commercial activity will be back next year.

Great group of people with varied interests, and a really provocative, expansive definition of “maintenance”

The 2018 Festival of Maintenance was an eye-opening event, bringing together people with incredibly diverse interpretations and experiences of what maintenance is all about who nonetheless touched on a bedrock of shared passions and commitments.

It was very helpful, and very timely, to get chance to hear experiences, expertise and ideas that framed maintenance as a counterbalance to the rhetoric of innovation, creativity and transformation.

Like discovering an entire other hemisphere of the world.

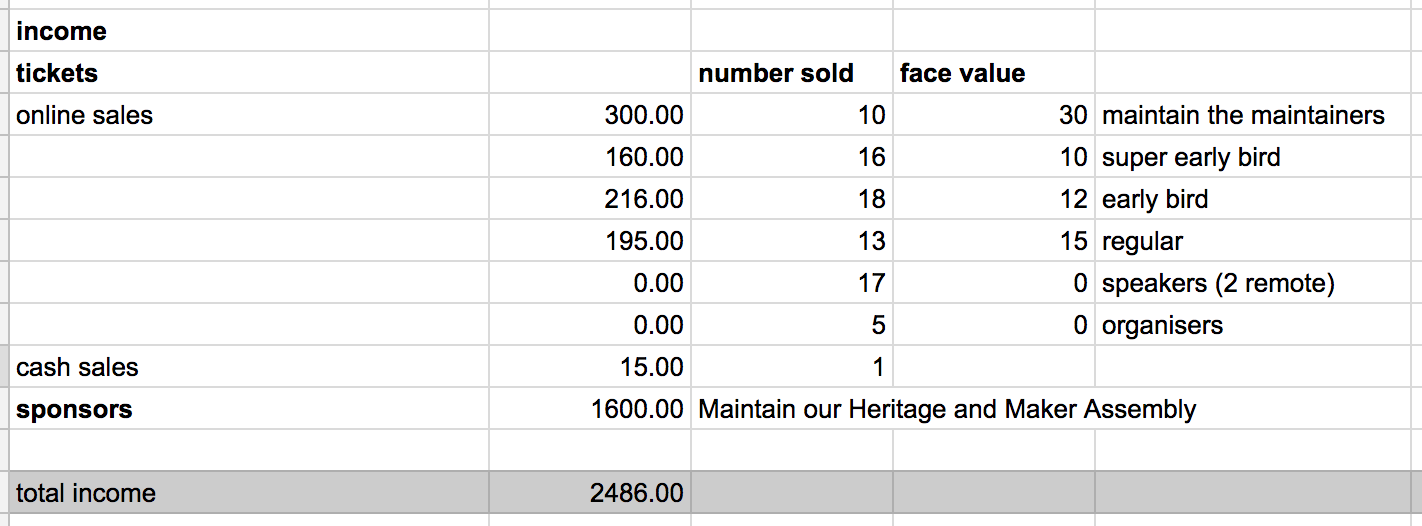

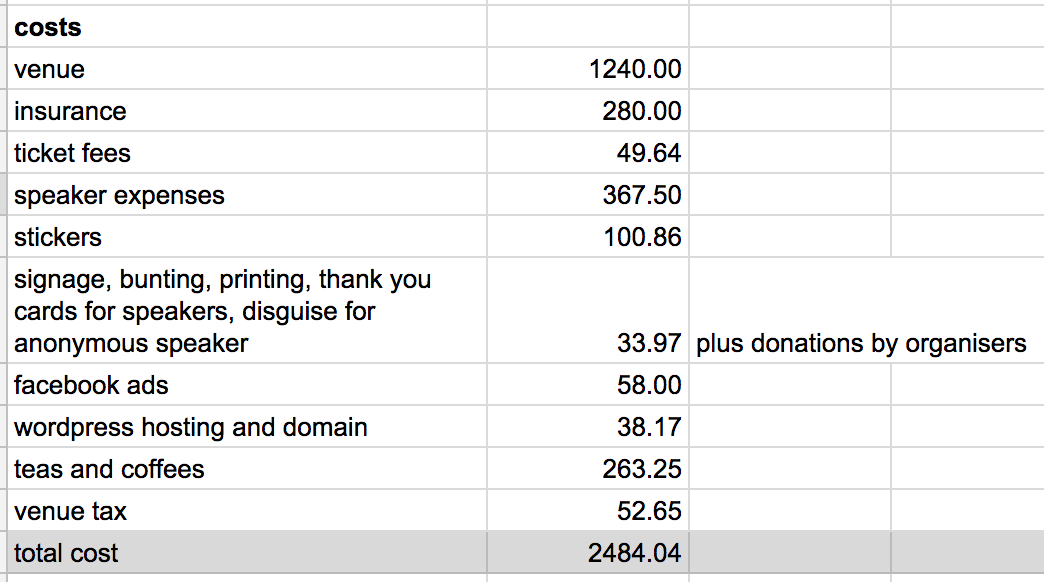

The event was run by volunteers and on a non-profit basis. Through a mix of good planning and good luck, we almost perfectly broke even financially.

We had 40 paying attendees plus 15 speakers plus 5 organisers on the day (plus 2 remote speakers).

Here’s some of the audience feedback:

See you next year!